Picture: Dr. Felix Fritschi, University of Missouri, while talking with China Agricultural University graduate students

Authors: Shannon K. King1,4, Jon T. Stemmle2, Robert E. Sharp3,4

1Department of Biochemistry, 2School of Journalism, 3Division of Plant Sciences, and 4Interdisciplinary Plant Group, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA

Second post of our “Global Collaboration” series

Earning a graduate degree in the life sciences is all about preparing students to become productive and competitive in today’s scientific field; ensuring they are at the cutting edge of technology and knowledge. However, one aspect of graduate education that is seemingly overlooked is extending outside of the lab and learning how to become a scientist in the global community. This oversight is something that scientists at the University of Missouri and China Agricultural University are working to combat.

In August 2018, faculty, graduate students and post-docs from both universities came together in Beijing for a workshop to discuss scientific areas of expertise ranging from wetland ecology to crop modeling. This allowed attendees to practice collaborating with other scientists internationally and across disciplines.

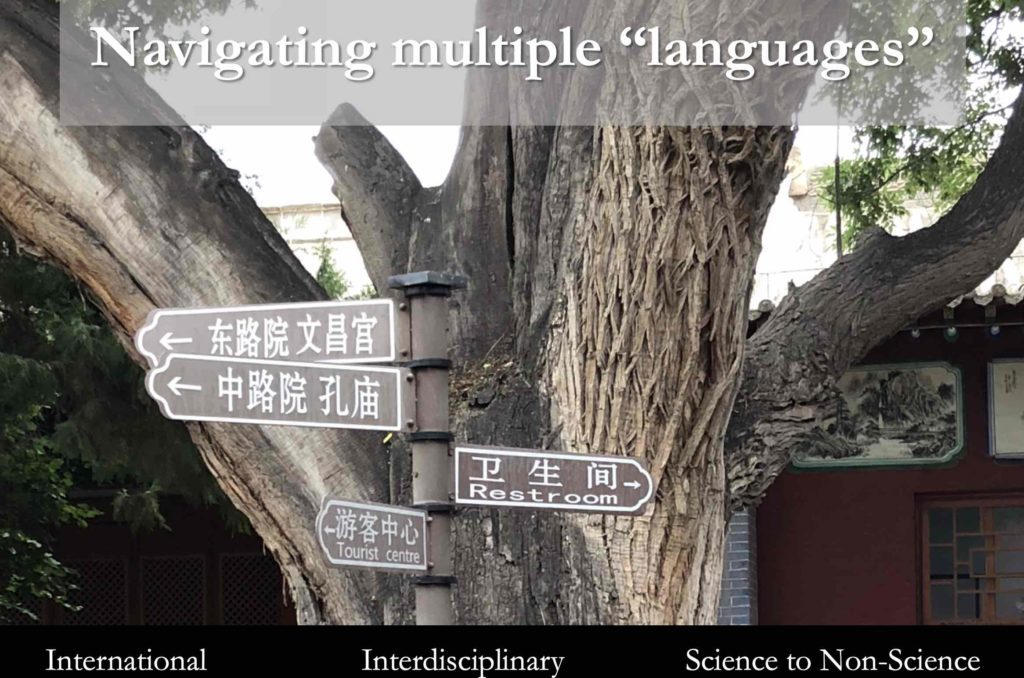

One of the key skills the graduate students developed during the workshop was how to communicate science in multiple languages. The students had to overcome the challenges of communicating science in English and Chinese along with explaining it to scientists outside of their disciplines and then take those experiences and turn them into videos, stories and blog posts that the public could enjoy.

Needless to say, the students quickly learned that not only is science communication difficult, but the degree of difficulty rises exponentially when trying to communicate with an audience outside of your native language and discipline. To tackle the language barrier, students avoided jargon and slowed their speaking pace to clearly articulate their points. Many times, the students from the two universities took the breaks between sessions to really talk to each other about the presentation content to solidify what the takeaways were. It was these informal discussions that led to very productive conversations. Students also pointed out the similarities and differences between their projects, allowing for bridges to be built between what would normally be very different fields.

Another part of this workshop helped the students to learn how to better engage with the general public. While in China, the Missouri graduate students performed journalistic tasks in order to demonstrate what they learned and experienced during the workshop. They took video footage, interviewed workshop attendees and conceptualized how to turn all of that content into stories. When the Missouri students returned home, they began the process of creating content about the China trip. They had to make sure all videos, blogs, and articles were easily understandable to a non-science audience since everything would be eventually posted online at https://rootsindrought.missouri.edu/ and on Youtube.

Through this experience, University of Missouri students were able to take what they had learned in theory and put it into practice. These skills will help them to have a unique advantage compared with their peers and help them as they move into their academic and professional careers.

There is no question that the scientific field is becoming more global and the general public is becoming increasingly skeptical of science. This makes it critical that we begin developing graduate programs to incorporate experiences that allow students to engage in the world outside the lab and learn to communicate why their science is beneficial to society, both at home and abroad.

Supported by NSF Plant Genome Program Grant no. 1444448 to R.E.S. and a 111 Program grant to Prof. Shaozhong Kang, China Agricultural University