Re-published with permission from Botany One. Author: Alun Salt

Why Tweet if you’re a scientist?

A common stereotype of Twitter is that it’s trivial and ephemeral. It’s certainly ephemeral, but it doesn’t have to be trivial if you’re interested in science. At Botany One we use our account more for keeping an eye on what is catching the interests of botanists than we do for self-promotion. If you have a focus on a particular topic, Twitter is an opportunity to get regular updates on news, papers and opportunities like jobs on a rapid basis. Twitter can be what you make it, but making it useful can be difficult. You can’t always find what you need to know in an instruction manual.

Below is a guide to setting up a science-oriented account on Twitter. It will cover the basic mechanics, like what is a tweet and how to do it. It’ll cover some of the elements that don’t get written up, like how to curate a network that works for you. You’ll also get some tips on gaining followers and how to deal with inevitable idiots.

The first draft of this article has been written in 2020. I’ll be updating it from time to time to reflect changing practices. That’s easy when there are new gadgets to explain, but the assumptions are also based in 2020. They can be more difficult to spot and re-examine.

Another factor is that I will be listening to feedback on this text, and updating it with other opinions. One way to start a good argument on Twitter would be to say This is the way to tweet and other ways are wrong. In reality, this is a way to tweet, but there are other ways. This is simply the way that works for me.

If you’re starting from a position of bewilderment, then that’s reasonable. It took me years to understand Twitter, and often I’m still bewildered.

What is a tweet?

At its core a tweet is a message of 280 characters. It used to be 140, and some tips you see on the web still refer to that limit. A lot of tweets are just text and it’s common to see tweets that are purely text commentary. Twitter has adapted to how users use the service to modify how it handles some text.

If a tweet has a link, then Twitter will look at the page that the tweet links. It then grabs some data from it, so people can see a preview of where the link leads. It will also shorten the link giving you more characters to use for a tweet.

As people started tweeting links to images, so too Twitter began hosting images and embedding them below tweets. You can now upload images from your phone or desktop computer to add to your tweet. It’s also possible to upload video. Audio is less supported, and many people browse Twitter with sound off, so you would probably want to include subtitles in your video if text were important to the message.

When people talk about tweets, they’re talking about these brief messages, sometimes with a little added content that people send. 280 characters doesn’t sound a lot, so to see how they work when they’re together you’ll need an account.

How to sign up for an account

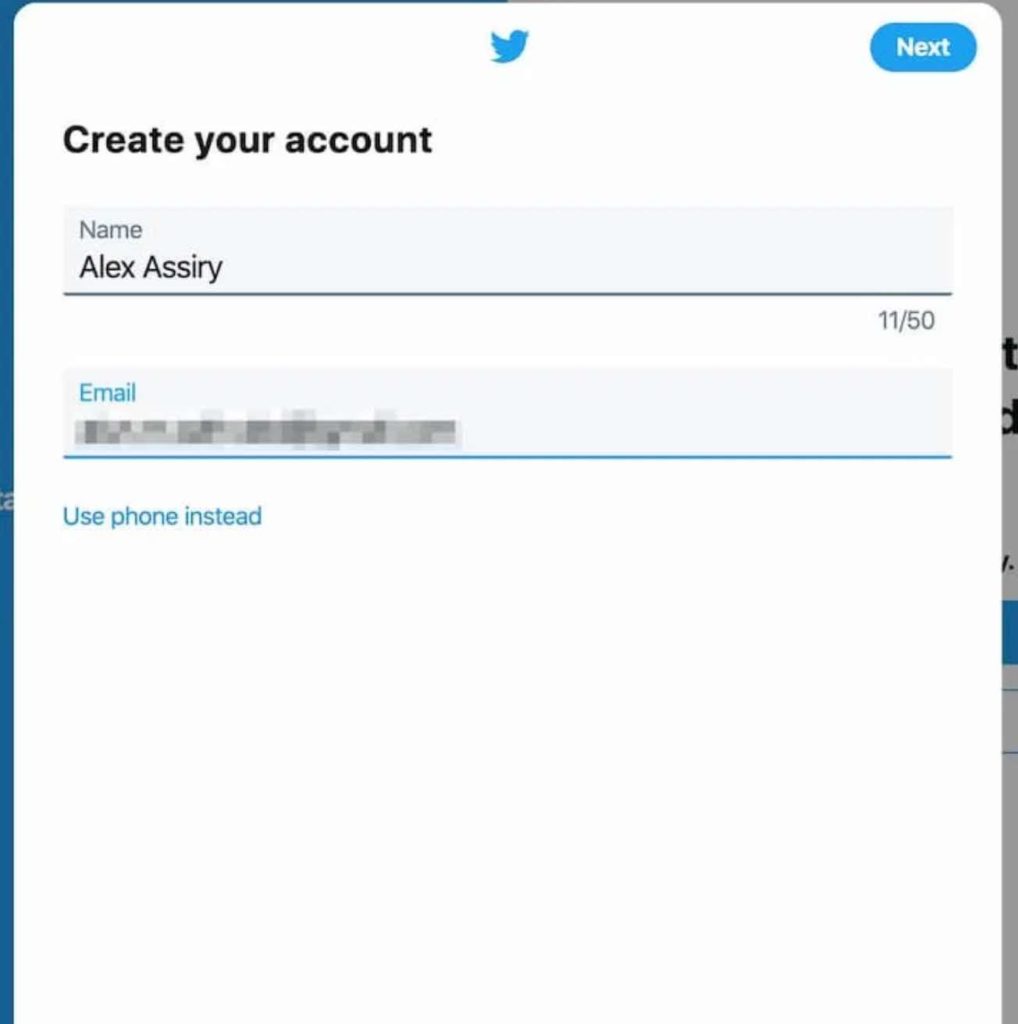

Go to https://twitter.com/ and you should see options to sign up or log in. You will want to sign up first, if you don’t have an account.

You’ll be asked to give your name and a phone number. You can use email instead. The idea of giving your phone number is that Twitter has an independent way to contact you when it sees someone log in to your account from an unusual place. That’s probably whenever you log in from a new computer, but it can help to have a phone number attached to an account.

Next you have the options to sign up to all sorts of emails, personalised ads and make it easy for people with your phone number to find you etc… You can leave all those blank.

Then you get another box saying you’re agreeing to terms and conditions.

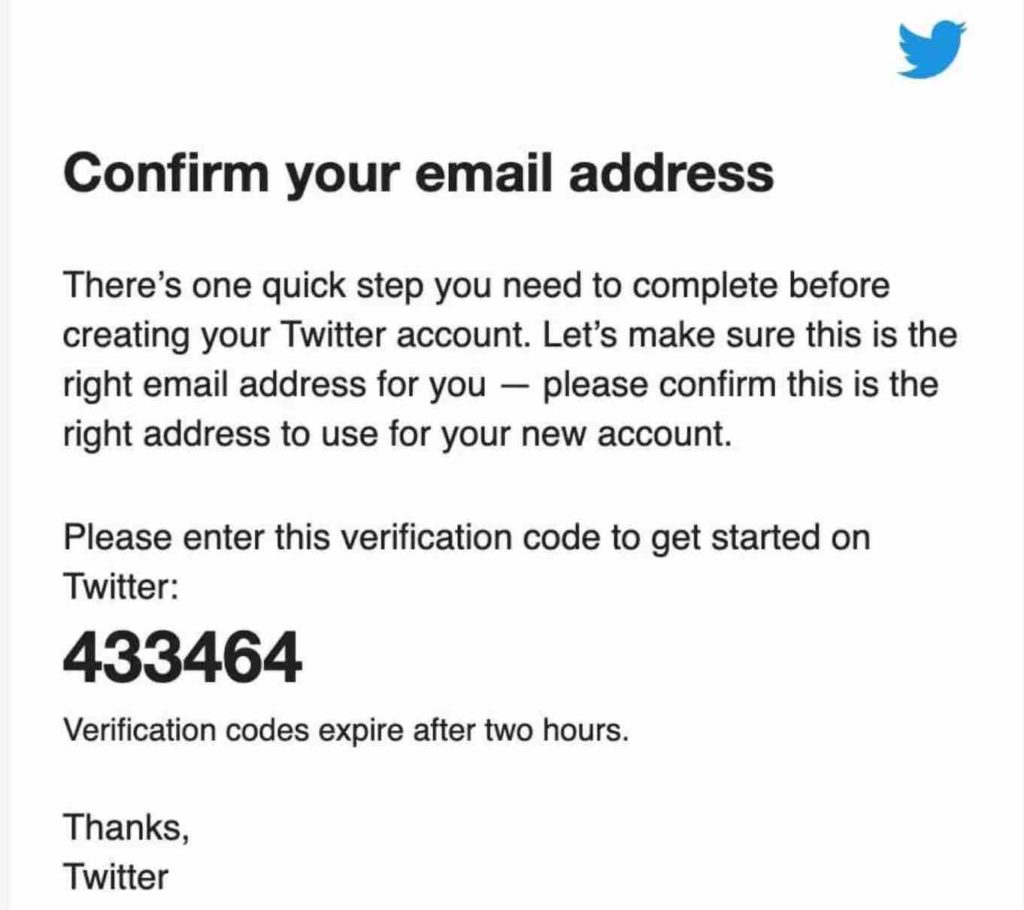

After that you get sent a six digit code to either your email or phone. This is a way that Twitter tries to reduce the number of robots signing up to Twitter.

Now you get to set a password. You’ll be able to use this password to use Twitter on your phone or through the web on a PC or laptop.

Add a profile pic

Next you’re asked to add a profile photo. If you don’t like any of your photos, then this is tough, but there is a good reason for putting a human face up. For a start, bots do not have faces. It also gives something for people to relate to. However, I can say this being a man. A photo could identify you as woman, or from an ethnic minority, and you could attract creeps in a way that I rarely do. If you can’t bear to have your face on your profile, other options would be hands on scientific equipment, or a shot of you at work, back to camera. Our editor (at the time of the first draft) Anne Osterrieder, suggests that you could, alternatively, create a cartoon avatar.

Describe yourself

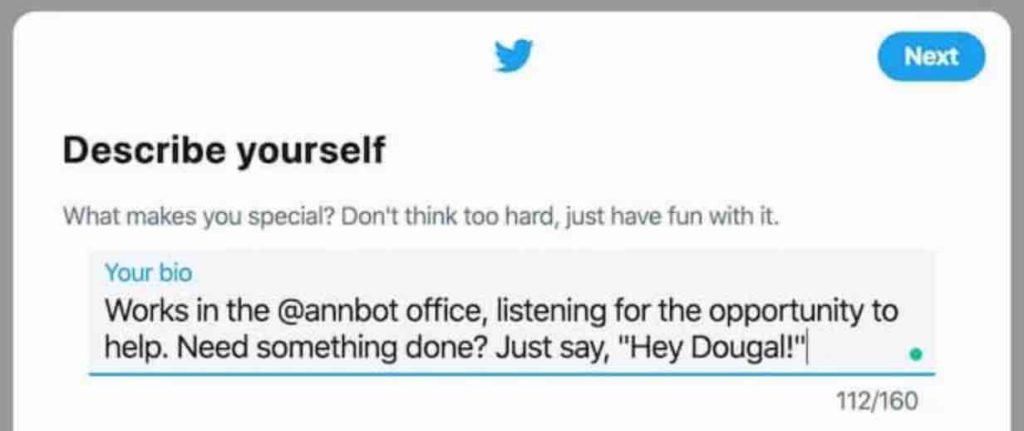

Add a short biography that appeals to the people you want to follow you. At Botany One we’re interested in botanists, so if you say Botanist or Plant Scientist in your biography, you’re more likely to get a follow. You might say Undergraduate student with an interest in plant pathology if you want to be more specific. Again it makes you look more human and also more relatable. Think about the keywords that people would use to find you, and make sure to use them in your bio.

Signal and Noise

Next you’re asked to upload contacts, skip this. You’re then asked for interests. Skip this too. Next comes suggestions of account to follow. Skip this.

The reason is that when you log in and go to twitter.com, you’ll see the tweets from the people and topics you follow. If you follow all your contacts, some topics and a few Twitter celebrities, your timeline will be busy, but it will be difficult to pull the science material out of it.

If you want to follow celebrities, there’s nothing wrong with that, but if you want to use Twitter for scientific networking as well, then you might find having two profiles is better than trying to do everything from one.

To get a science-focussed twitter account, it helps to follow the right people.

Who to follow and why

When you’re signed in to Twitter, when you go to https://twitter.com/ you don’t see your tweets. You see the tweets of the people you follow. So choosing who to follow will play a big role in making your Twitter experience.

If you’re interested in following people in botanical science, then the best place to start is with journal papers. If you visit a journal paper published in your field, there’s a good chance it’ll have a circle graphic and a number marked Metrics or Altmetric. Click on this and you’ll get a summary of social media chatter about the paper. Click on the Twitter tab, and you’ll see a list of tweets of people talking about the paper. It’s a list of people talking about something you’re interested in.

Next you could pick a few more papers and see who else there is to follow, or you could look to see who the people you follow are retweeting. Personally with a new account, I’d get to about 100 people to follow and then stop. The reason for this is that some people will follow others simply to get attention. If you follow hundreds of people at once, and no one is following you as you have a new account, then – at best – you’ll look a bit desperate.

As well as people, you could follow journals and top-quality botanical blogs. I recommend In Defense of Plants (@indfnsofplnts). But you’re under no obligation to do so. If you’re following the right people, then you’ll see them pick out relevant papers from journals for you.

Following is asymmetrical

Just because someone is following you, you do not have to follow them. And also if you follow someone, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will want to follow you. Controlling who you follow is the best way of reducing noise and increasing signal on Twitter. The people you follow will produce the tweets you see when you log in and go to twitter.com.

How to gain followers

It’s easy to say follower numbers don’t matter. It’s even easier to say that when you have a few thousand people following you. If you’re on Twitter to network and make a connection then it’s natural you’d like people to follow you. I try to follow people from the @botanyone account, so below is a list of things that you can do to make it more likely that I’ll follow you.

Change your Twitter handle

Twitter usually assigns you a bad name these days like @Name7583976. Change that to something that’s more you. This might take some time. I was going to suggest @HelenPollen, if your name was Helen and you’re into pollination, but that’s been taken. To be fair, it’s very unlikely that you fit that criteria, but spare a thought for any Helens reading this who might be feeling freaked out. The reason that changing your name is a good idea is that people running bots and sock puppet accounts rarely do this, so it gives people a bit more confidence that they’re following a person rather than a propaganda tool. If you want to change your name at a later point, you can do this without losing your existing followers (if it is still available).

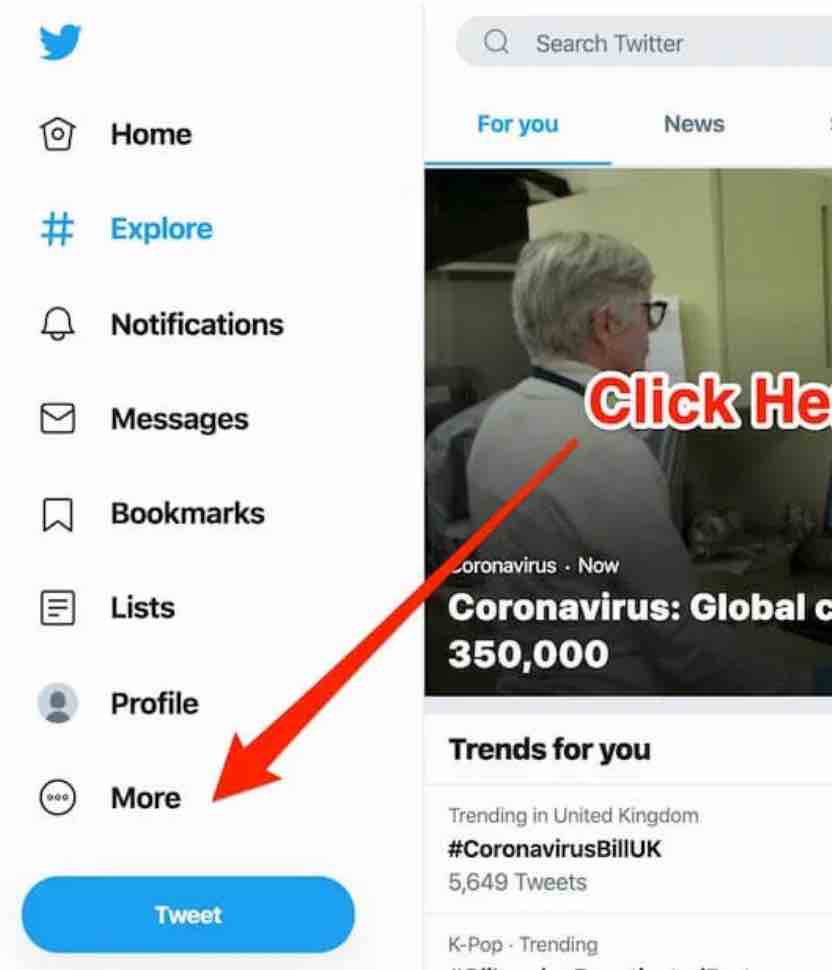

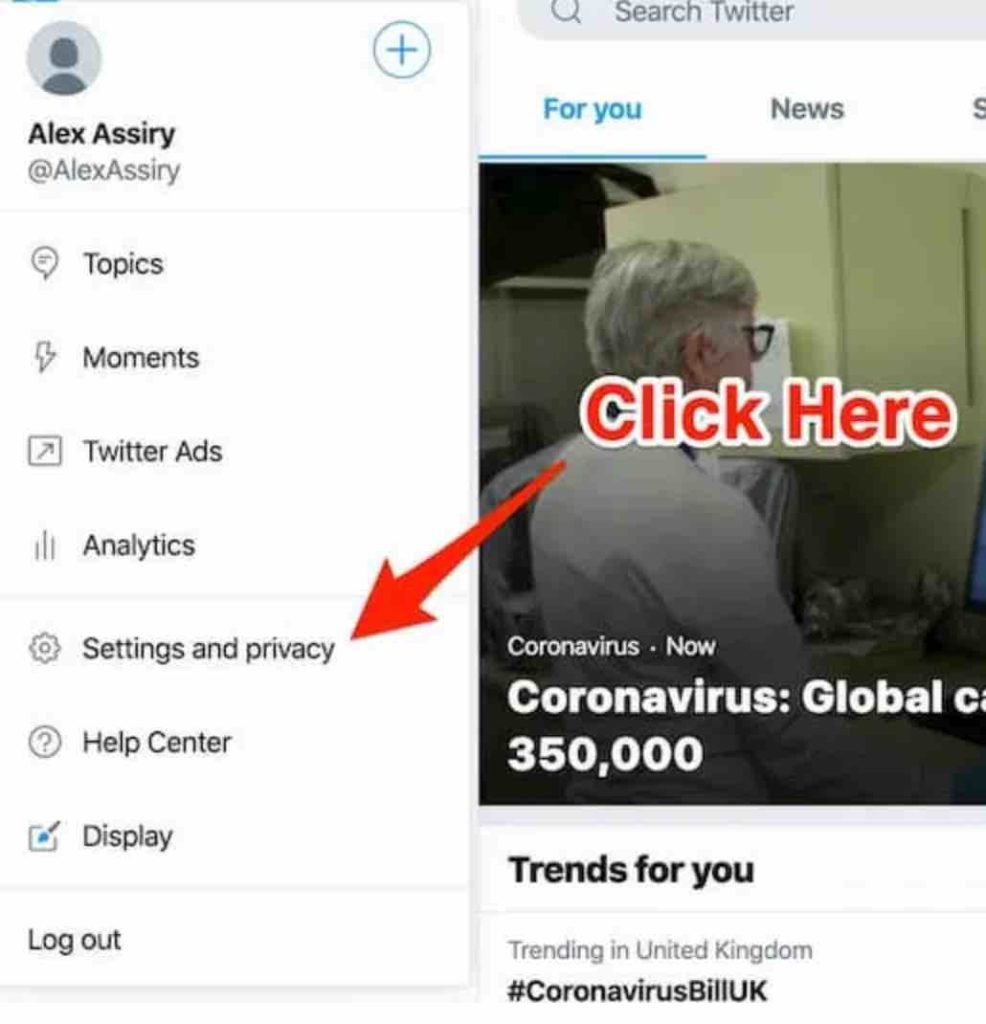

To change your name, click on more, if you’re at a PC or laptop.

Up will pop a menu, you’ll want Settings and Privacy.

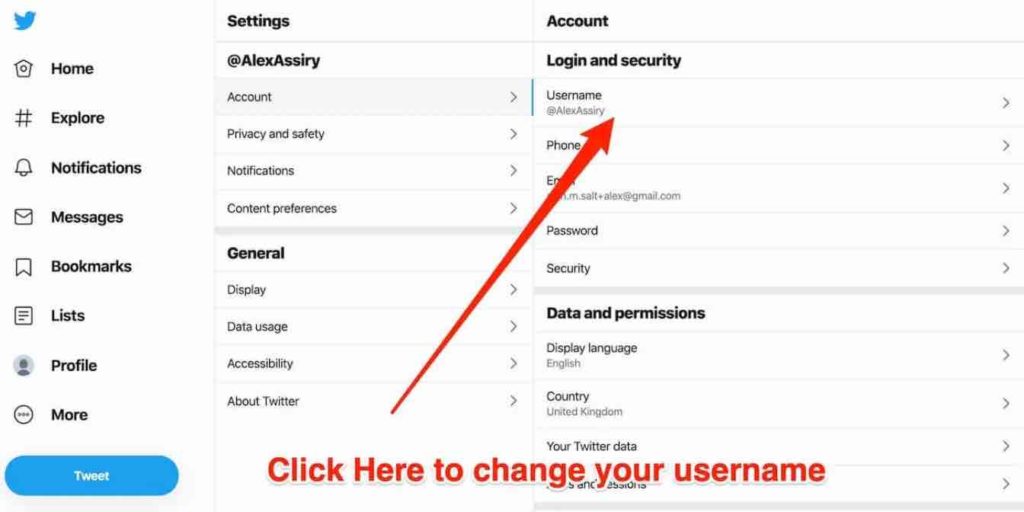

Next click on your username to change your username.

Unhelpfully, in this example, Twitter hasn’t found another AlexAssiry, so I’ve no need to change this username, but you might not be so lucky.

Tweet interesting things

If you have a brain, then this should sound like unhelpful advice, like someone saying ‘say something’ when they want to test a microphone. There are some short-cuts.

One is to discover something amazing and then tweet about how you found it. Or work in an exotic location. I can’t help you discover something, but I can help you with the location. If you live in Tokyo, the most populous city on the planet, you live with over 38 million other people. You might think it’s nothing special. I live six thousand miles from Tokyo and, to me, it’s an exotic and exciting place. If you live in a less populated settlement, which is almost everyone on Twitter, then it’s likely that you’ll live somewhere that’s exotic to many people. Find the things about your work, your location or your plants that make your place unique.

In my case, interesting things are botanical things. If someone follows @BotanyOne, then I am most likely to follow back if the person is tweeting about plants. It doesn’t have to be every tweet about plants, but I’d like to see that a person is saying something about Botany. If you want to attract palaeoecologists then make sure that when people visit your profile page, they don’t have to scroll far to see something about palaeoecology.

Share interesting things

If you’re researching something, then there’s a good chance you’ll have read an interesting paper this week. What was it? If you visited papers to see who to follow (see above) then you’ll see many people sharing papers. You could do this, or with just a little tweak, you could do something more interesting.

When people share a paper, there’s a good chance that they’ll see a preview of the paper, or at least its title in the link. So if you read a paper titled “What Happens When you Hit Arabidopsis with a Stick?” it doesn’t add much information if you just re-iterate the title. However, all scientific papers have abstracts that should tell you why the authors think they’re interesting. Quote a sentence or two from that abstract that shows why you found the paper so interesting. All researchers agreed that while it was strangely satisfying to hit Arabidopsis with a stick, it was a mistake to mix gin with lab work.

Adding this slight tweak will give your tweets more information than most shares of the paper, and takes little brain power. If you could use brain power to provide original commentary on the paper – even better!

Share things other people find interesting

If you tweet purely about yourself, it can look like you’re only interested in self-promotion. If you want to make meaningful connections on Twitter, you should also take an interest in other people. Also, writing all of your own tweets is a lot of work. What you can do is re-tweet other people.

Twitter has a retweet button. If you click this then the tweet will be shared with people who follow you, with credit to the original author. Doing this you can share the most interesting things you see on Twitter and put them alongside your own tweets. When you do this you’re telling the people you retweet that you find them interesting, which is (usually) a friendly act.

It also reminds the people following you that you’re active.

Talk to people

There’s a comment by Erin Zimmerman on the culture of talking to people on the Canadian Science Publishing blog. “One of the harder parts of social media for a lot of people, especially non-digital natives, is learning that in most cases it’s okay to jump into conversations with people you don’t know. It’s jolting at first, but if you wait for an invitation it will never come.”

If replying to someone you’ve never met is a social step too far, then why not simply tell someone you liked their paper / blog post / photo, if they’re on Twitter? To do this, include their username with an @ at the front and they will get an alert about it. So if you type @botanyone somewhere in a tweet, I will see it.

(This is why I no longer use @alun as my primary account. It turns out alun-alun is a town plaza in Indonesia, so whenever two people were meeting up @ the town centre, @alun-alun I was the first to know about it. Indonesia is the fourth most populous country on the planet, and at the weekend a good number of Indonesians like to party in town.)

What not to tweet

This might be a controversial section for some readers. Usually telling people you’re doing social media wrong is a good way to cause offence. People take it as having their speech policed. However, there are some factors to take into account if you don’t want to accidentally cause offence.

Every tweet is an introduction to you

Sometimes, you might want to deliberately cause offence. In these situations, it’s important to remember that most people reading your tweets will either be seeing your account for the first time. If you tweet something out of character as a joke like, Yawn is there a plant less interesting than Drosera? then that’s not likely to come across as out-of-character if it’s the only tweet of yours that someone has seen. This could be a problem if you’re obsessed by Drosera and you’ve just alienated a fellow Drosera researcher. It’s a pain, but the internet doesn’t do context or humour very well.

The oxygen of publicity

Sooner or later you read a bad paper. You could tweet how awful a paper is. This might be a bad idea for various reasons, but one is that Altmetric counter. When you tweet about how bad a paper is, it shows up as attention on that counter in exactly the same way as a positive comment.

It also appears in your feed spreading the message further, and if you may be followed by another person with bad judgement who wants people to read the paper.

I’m not saying never comment on a bad paper, but I would say to think about whether the benefits outweigh the costs. At Botany One I don’t blog papers I don’t link because it takes effort and I’d rather spend my remaining heartbeats promoting good science than wasting them on rubbish.

Piling on as a marker of social status

Another thing you might want to avoid is a pile-on. Sooner or later someone will say something moronic, like Yawn is there a plant less interesting than Drosera? Some people might think that’s an opinion, you might know it’s wrong, but I think it’s outrageous to say that and it is entirely unacceptable to tweet such nonsense. By having the more extreme reaction, I’m demonstrating that my standards are higher than yours and so, presumably, I’m the more serious botanist.

I don’t think people are always consciously posing with outrage when they do this. But sometimes, yes, people are using pile-ons to bolster their own social status. In the long term it will damage your credibility.

The counter-argument is that mass opprobrium can lead to change in behaviour. So again, I wouldn’t say never join in an argument, but at least make sure it’s an argument worth your attention.

Also remember that people like Piers Morgan thrive on the attention. It shows to his employers that he’s still relevant.

How to deal with trolls

Another sad fact of Twitter is that there are trolls. These are people who want your attention and to snipe at you.

As an example I had someone complain when I covered the fires in the Amazon. These happen every year, they said. The fact they were happening in record numbers in 2019 was irrelevant. He later complained to me that Greta Thunberg had arrived in New York and wanted me to do something about that. It’s flattering, that someone thinks I’m that important. What he really wanted was for me to start engaging with him, because the time I spent responding to him would be time I wasn’t spending compiling a newsletter that mentioned forest fires, climate change or invasive species.

The goal of the troll is not to seriously get you engaged in scientific debate. It’s to drain your time and energy to prevent you from doing whatever it is you are doing. Time spent trying to inform him of science (that he already knows and doesn’t care about) is time that you could have spent informing a dozen people who might genuinely appreciate your efforts.

The way to engage with trolls is to block or mute them. There is a button where you can block people and you don’t see their tweets again. This does annoy them, but you’re obliged to listen to these people in the same way you’re obliged to listen to a drunken racist in the park. If it helps you can make a ‘ker-splat’ noise as you block them.

Occasionally someone will set up a second account to complain about you blocking them. Imagine how annoyed they are when you block them again.

Another alternative is to mute people. In this case people don’t know they’ve been muted. They can still see your tweets, but you don’t see theirs. The important rule in this situation is to do whatever maximises your peace of mind. You owe trolls nothing.

Twitter is not set in stone

This is how I’m approaching Twitter in early 2020. It changes. When I first started there were no embedded images or videos. You couldn’t promote things. You could see EVERYTHING people posted to Twitter. To retweet someone you had to type RT @Name at the start of a tweet, which cost you characters. This is no longer the case.

As the site evolves, how you can use it evolves. Also as you change, how you want to use the site will change. This is how I use the site at this time. Copy what works for you, and ignore what doesn’t to make your own way of using Twitter.

And if there’s something that you think would be helpful to know that I’ve missed then you can tweet @BotanyOne and let me know about it. I shall shamelessly update the post with other opinions over time.