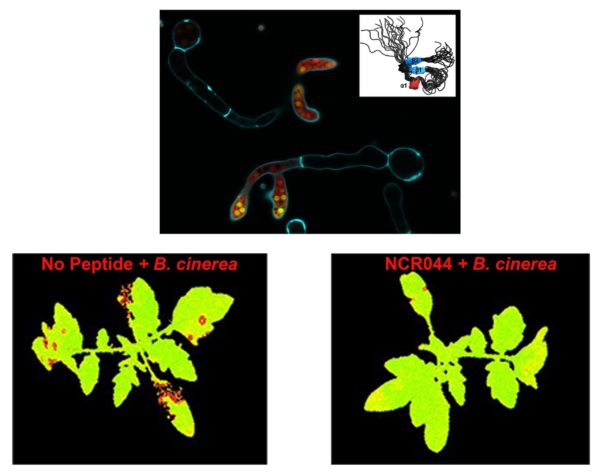

Findings pave the way for developing environmentally friendly fungicides. Fungal diseases cause substantial losses of agricultural harvests each year. The fungus Botrytis cinerea causing gray mold disease is a major problem for farmers growing strawberries, grapes, raspberries, tomatoes and lettuce.…

Read More