Ecologists develop models that identify major threats to a dominant tree family in the Philippines. Already reduced by deforestation, climate change is set to further undermine their survival.

Ecologists develop models that identify major threats to a dominant tree family in the Philippines. Already reduced by deforestation, climate change is set to further undermine their survival.

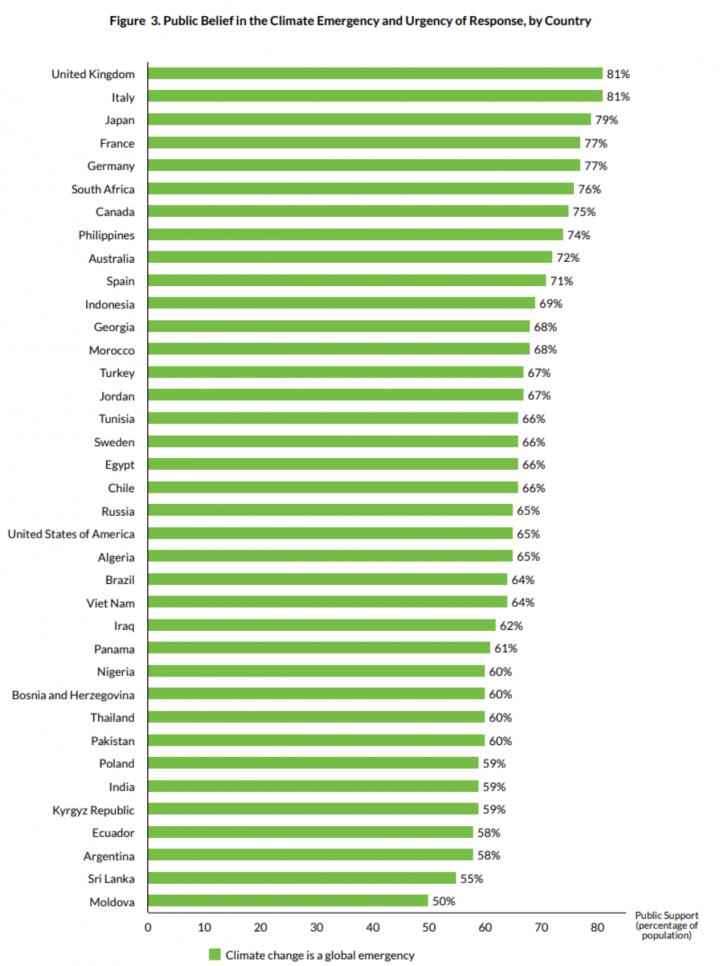

The results of the Peoples’ Climate Vote, the world’s biggest ever survey of public opinion on climate change are published in January. Covering 50 countries with over half of the world’s population, the survey includes over half a million people under the age of 18, a key constituency on climate change that is typically unable to vote yet in regular elections.

Detailed results broken down by age, gender, and education level will be shared with governments around the world by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which organized the innovative poll with the University of Oxford. In many participating countries, it is the first time that large-scale polling of public opinion has ever been conducted on the topic of climate change. 2021 is a pivotal year for countries’ climate action commitments, with a key round of negotiations set to take place at the UN Climate Summit in November in Glasgow, UK.

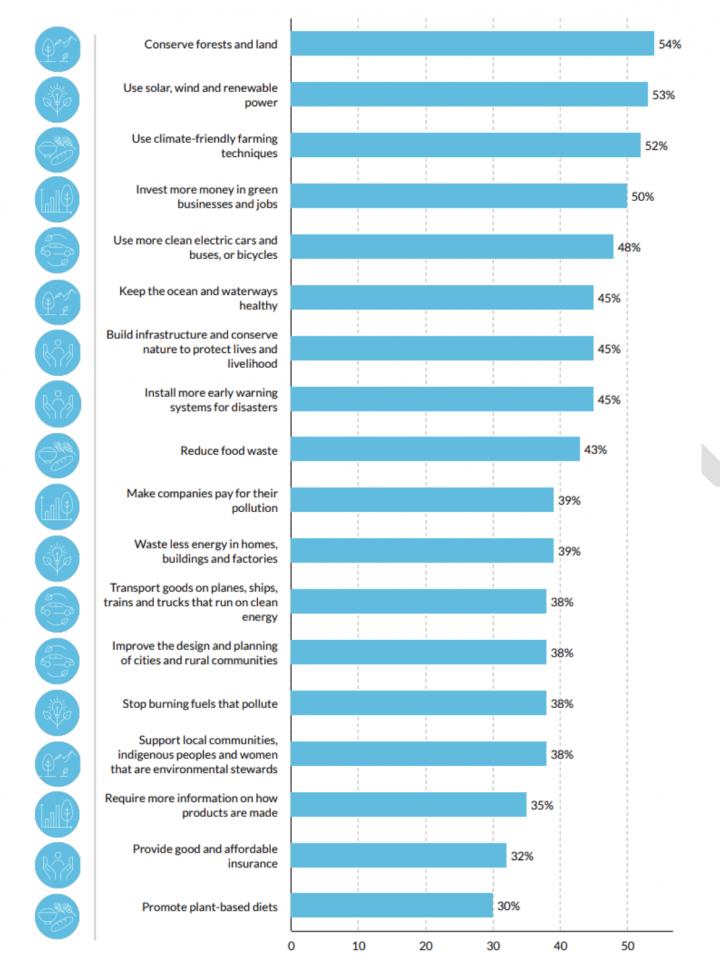

In the survey, respondents were asked if climate change was a global emergency and whether they supported eighteen key climate policies across six action areas: economy, energy, transport, food & farms, nature and protecting people.

Results show that people often want broad climate policies beyond the current state of play. For example, in eight of the ten survey countries with the highest emissions from the power sector, majorities backed more renewable energy. In four out of the five countries with the highest emissions from land-use change and enough data on policy preferences, there was majority support for conserving forests and land. Nine out of ten of the countries with the most urbanized populations backed more use of clean electric cars and buses, or bicycles.

UNDP Administrator Achim Steiner said: “The results of the survey clearly illustrate that urgent climate action has broad support amongst people around the globe, across nationalities, age, gender and education level. But more than that, the poll reveals how people want their policymakers to tackle the crisis. From climate-friendly farming to protecting nature and investing in a green recovery from COVID-19, the survey brings the voice of the people to the forefront of the climate debate. It signals ways in which countries can move forward with public support as we work together to tackle this enormous challenge.”

The innovative survey was distributed across mobile gaming networks in order to include hard-to-reach audiences in traditional polling, like youth under the age of 18. Polling experts at the University of Oxford weighted the huge sample to make it representative of the age, gender, and education population profiles of the countries in the survey, resulting in small margins of error of +/- 2%.

Policies had wide-ranging support, with the most popular being conserving forests and land (54% public support), more solar, wind and renewable power (53%), adopting climate-friendly farming techniques (52%) and investing more in green businesses and jobs (50%).

Prof. Stephen Fisher, Department of Sociology, University of Oxford, said: “The survey – the biggest ever survey of public opinion on climate change – has shown us that mobile gaming networks can not only reach a lot of people, they can engage different kinds of people in a diverse group of countries. The Peoples’ Climate Vote has delivered a treasure trove of data on public opinion that we’ve never seen before. Recognition of the climate emergency is much more widespread than previously thought. We’ve also found that most people clearly want a strong and wide-raging policy response.”

The survey shows a direct link between a person’s level of education and their desire for climate action. There was very high recognition of the climate emergency among those who had attended university or college in all countries, from lower-income countries such as Bhutan (82%) and Democratic Republic of the Congo (82%), to wealthy countries like France (87%) and Japan (82%).

Note:

The percentage of a population estimated to support a particular policy does not indicate that those who did not are against the same policy, since not endorsing a policy could also be due to indifference to it. The country results present what people think who are physically in a particular country. They are not representative of what nationals of a particular country think. So for example, they are representative not of what French people think, but of people in France.

Read the report: United Nations Development Programme

Article source: United Nations Development Programme via Eurekalert

Image credit: UNDP

Deforestation dropped by 18 percent in two years in African countries where organizations subscribed to receive warnings from a new service using satellites to detect decreases in forest cover in the tropics.

You might have observed plants competing for sunlight — the way they stretch upwards and outwards to block each other’s access to the sun’s rays — but out of sight, another type of competition is happening underground. In the same way that you might change the way you forage for free snacks in the break room when your colleagues are present, plants change their use of underground resources when they’re planted alongside other plants.

New research has demonstrated how, in contrast to encroachment by the invasive alien tree species Prosopis julifora (known as `Mathenge` in Kenya or `Promi` in Baringo), the restoration of grasslands in tropical semi-arid regions can both mitigate the impacts of climate change and restore key benefits usually provided by healthy grasslands for pastoralists and agro-pastoralist communities.

Global warming already affects Siberian primrose, a plant species that is threatened in Finland and Norway. According to a recently completed study, individuals of Siberian primrose originating in the Finnish coast on the Bothnian Bay currently fare better in northern Norway than in their home area. The results indicate that the species may not be able to adapt to quickly progressing climate change, which could potentially lead to its extinction.

In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic and the mounting threat of climate change, forests and trees are vital for the rural poor in countries around the world. However, the poor are rarely able to capture the bulk of benefits from forests. A global science assessment analyses how forests can realize their potential to reduce poverty in a fair and lasting manner.

Tropical forests may be more resilient to predicted temperature increases under global climate change than previously thought, a study published suggests. The results could help make climate prediction models more accurate, according to the authors.

Europe’s forests face a growing threat from pests due to global trade and climate change, but scientists are developing techniques that can give an early warning of infestations to help combat damaging insects and diseases.

Pests are responsible for damaging 35 million hectares of forest around the world every year. In the Mediterranean region alone an area the size of Slovakia – five million hectares – is affected by pests annually, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

And the threat posed by insects and pathogens appears to be growing. Climate change is allowing some native pests to breed more frequently, while international trade is spreading exotic insects and pathogens more widely.

Only a tiny proportion of exotic pests that arrive in Europe end up damaging trees. ‘But these are very harmful, and there are more and more (of them),’ said Dr Hervé Jactel, director of research for forest entomology and biodiversity at the French National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment.

On average, six new species of tree pests are being introduced to Europe every year, up from two a year in the 1950s, says Dr Jactel. They arrive in potted plants and wooden products or packaging.

Many of the emerging threats to Europe’s forests originate in Asia.

The emerald ash borer, for example, spread from Asia to the United States where it killed more than 150 million trees and may have cost more than $10 billion in the last decade. It is now knocking at Europe’s door.

‘We know it will kill all ash trees, or most of them,’ said Dr Jactel, who is the coordinator of the HOMED project which is developing new ways to detect such exotic pests early.

The polyphagous shot-hole borer is another major threat. It can attack virtually all deciduous tree species in Europe, says Dr Jactel.

‘It’s a very, very dangerous tiny beetle,’ he said. ‘This is probably the next big issue for Europe.’

This little insect originated in Asia, spread to Israel, California, and then South Africa where it has killed hundreds of thousands of trees. In April this year it was discovered for the first time in Italy, in a tropical garden. There is no sign yet that it has spread anywhere else in Europe.

Despite all of the countries affected by the beetle being on the alert for it, none were able to detect it until it had already caused damage, says Dr Jactel. The problem is spotting exotic pests and pathogens before they start attacking trees.

Hundreds of thousands of containers filled with goods arrive in Europe’s harbours and airports every day. Tiny insects or spores from fungal diseases can stow away in shipments containing wooden products, pallets or packaging, or live plants. The sheer number of shipments is overwhelming the resources of sanitary inspectors to detect insects and spores, says Dr Jactel.

‘It’s like finding a needle in a haystack.’

Solutions

Once the containers are opened, pests can then easily escape to nearby trees. So increasing surveillance of trees growing around ports and airports is a good starting point, says Dr Jactel.

Finding solutions to these pests is vital. Forests cover 43% of the EU’s land area – 182 million hectares in total – and growing. The forestry sector accounts for approximately 1% of EU GDP, and provides jobs for some 2.6 million people. If allowed to run rampant – without the natural predators found in their native habitats and among trees that have not evolved defences against them – the pests could be devastating.

But new tools are also needed to alert inspectors to the presence of pests in containers before they can escape, he adds.

The HOMED team are developing generic traps to attract a wide variety of insects. These will be placed in shipping containers before they set off from their country of origin, and in airports, harbours and train stations where the imports arrive.

The teams are also developing traps for fungal spores, and DNA tools and databases of species to help identify whether a spore is local or imported.

The project is also planting ‘sentinel’ European trees in Asia, North America and elsewhere that can help scientists identify early which pests might pose a particular threat to European trees.

For pests that have already taken hold in Europe, one possible solution is to import that pest’s natural enemies from its country of origin, says Dr Jactel.

Scientists in France and Switzerland are investigating whether the natural enemies of the destructive box tree moth – which has spread from China across Europe – can be imported and used to contain it. But releasing this parasitic wasp to target the moths might bring other problems.

‘We need to be very cautious to check the Chinese parasitoids won’t affect European species,’ said Dr Jactel.

Native pests

Many threats to Europe’s forests, however, are closer to home. A warming climate in many regions is helping some native pests to become more common.

The bark beetle is one of the most damaging pests currently attacking Europe’s forests, destroying spruce trees in Central Europe.

The Czech Republic has had to cull so many infected trees in recent years the price of wood has plummeted as the resulting timber has been sold off, says Dr Julia Yagüe, project manager of My Sustainable Forest (MSF), which monitors the health of Europe’s forests. Spruce trees take up to 140 years to fully grow, so the loss of so many trees will be felt for a long time.

This is largely because warming temperatures have allowed the beetles to breed more frequently.

‘Some 20 years ago, we’d have one breeding cycle per summer, but nowadays we have up to four breeding cycles of bark beetle in the Czech Republic and southern Germany,’ said Dr Yagüe.

Warmer, longer and drier summers also mean trees are more vulnerable to attack because the conditions leave them less able to cope with pests, she says.

Scientists are creating variations of native spruce trees, which they hope will be more resistant to higher temperatures and drought, and so better able to fight off attacks from pests.

But in the meantime, forests urgently need closer monitoring, says Dr Yagüe. Forest managers usually take an inventory once every five to ten years.

‘Because climate change is pressuring so hard, we need to update our data on forests much more often,’ she said.

The most efficient way to monitor large forests is with satellite observations, which can help detect the early warning signs of trees that are under water or heat stress, and so are more susceptible to attack.

They can also allow forest managers to spot the first signs of an infestation, such as dryness, loss of foliage, or dieback.

‘With remote sensing from satellites we can spot this sickness before even the human eye can detect it,’ said Dr Yagüe, who is a remote sensing expert at the Spanish aerospace company GMV.

MSF’s job of gathering data became easier with the launch of Europe’s Copernicus satellites in 2014, and the development of technology able to process huge amounts of information.

MSF now receives snapshots of Europe’s forests every five days instead of every 15 to 30 days before Copernicus. ‘We get this information for free,’ said Dr Yagüe.

But there is another crucial element to improving the health of Europe’s forests which is much closer to home.

Many of Europe’s forests have been abandoned. While they were once carefully managed landscapes, as people moved to cities, ‘the knowledge of living together with nature has been lost’, said Dr Yagüe. ‘Recovering this is super important.’

The research in this article was funded by the EU.

Article source: Horizon Magazine

Author: Alex Whiting

Image: The emerald ash borer has killed more than 150 million trees in the US in the last decade and is a potential threat to Europe’s forests. Credit: Pikist, public domain

Miniscule plants growing on desert soils can help drylands retain water and reduce erosion, researchers have found. A global meta-analysis led by UNSW scientists shows tiny organisms that cover desert soils—so-called biocrusts—are critically important for supporting the world’s shrinking water supplies.