A new study demonstrates that there are no simple or universal solutions to the problem of engineering plants to enable them to cope with the challenges posed by climate change.

A new study demonstrates that there are no simple or universal solutions to the problem of engineering plants to enable them to cope with the challenges posed by climate change.

Improper adoption of climate impact modelling could leave us ill prepared for even higher temperatures and more frequent heatwaves, according to new research.

The size and ferocity of the Australian fires this summer has shocked us all. This is just the beginning of catastrophic climate change – next year may be better, we may even have several years in a row without major fires but there is no doubt that we will see further destruction until the cause of global warming is addressed and CO2 emissions are curtailed.

Botanists from have discovered that “penny-pinching” evergreen species such as Christmas favourites, holly and ivy, are more climate change-ready in the face of warming temperatures than deciduous “big-spending” water consumers like birch and oak. As such, they are more likely to prosper in the near future.

The catastrophic bushfires raging across much of Australia have not only taken a huge human and economic toll, but also delivered heavy blows to biodiversity and ecosystem function. Scientists are warning of catastrophic extinctions of animals and plants.

Climate change sceptics may be a minority, but they are a sizeable one. One in five Americans think that climate change is a myth, or that humans aren’t responsible for it. They’re a vocal minority too and a serious obstacle to collective climate action. So what can we do about them?

Success with improving Arabidopsis mitochondrial respiration in response to harsh conditions is leading plant molecular researchers to move to food crops including wheat, barley, rice and chickpeas.

A new study reveals how sorghum crops alter the expression of their genes to adapt to drought conditions. Understanding how sorghum survives could help researchers design crops that are more resilient to climate change.

Biologists have described a new molecular mechanism that allows plants to optimize their growth under suboptimal high-temperature conditions.

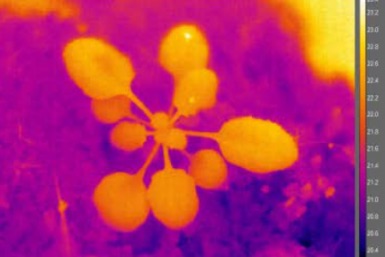

Researchers have revealed the role of genes in controlling flowering time in the Brassica rapa family. They demonstrated that a higher level of FLC gene expression is essential for inhibiting flowering in the absence of a cold period and also discovered that the rate of repression of FLC expression during a cold exposure affects the time of flowering. It is hoped that this understanding can contribute to the efficiency of B. rapavegetable cultivation in the face of climate change.