This week’s blog comes from Rachel Shekar, the project manager for the “Crops in silico” project.

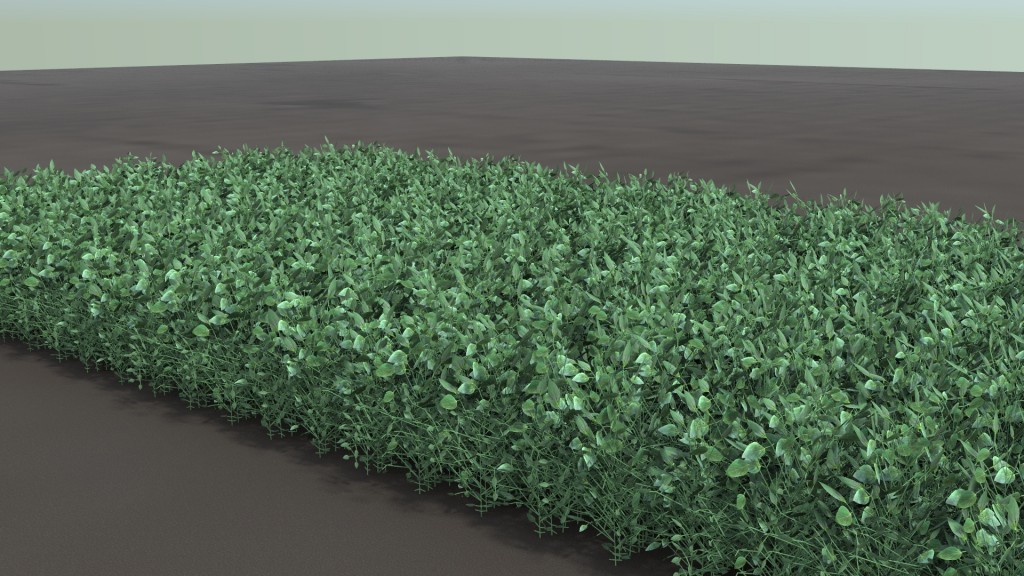

Researchers watch a field of soybean emerge, grow, and abruptly die in the span of one minute — on their computer screens. These virtual crops will help them understand how crops will respond to climate change – an ever-growing threat to worldwide food production – and could lead to overcoming its threat to global food security.

It is estimated that, by 2050, food production will need to increase by 70% to meet the demands of a growing global population. According to the latest UN projections, the world’s population will rise from 6.8 billion today to 9.1 billion in 2050 – a third more mouths to feed than there are today. Nearly all of the population growth will occur in developing countries.

At the same time as demand for food is increasing, the world will also be facing fresh water scarcity and climate change.

Climate change is expected to bring warmer temperatures, changes to rainfall patterns, and increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events. Although projections vary, it is clear that crop yields will decrease as climate change increases. Furthermore, the countries that most need food – such as sub-Saharan Africa – are the very places that will be most severely affected by climate change. Growing water use and rising temperatures are expected to further increase water stress in many agricultural areas by 2025.

Soy field. Image credit: Neil Palmer (CIAT). Used under license: CC BY-SA 2.0.

Can crop yields be increased in time?

The introduction of new crop varieties that produce higher and more stable yields in the face of drought, heat, diseases, and other stresses will allow farmers to grow crops that are adapted to climate change.

Plant models can be used to rapidly identify genes that will improve yields and utilize resources more efficiently, which will provide targets for developing productive varieties of food crops more quickly than ever before.

Because many traits, such as yield, are controlled by interactions between genetics, the environment, and the ecosystem, the most accurate results can be obtained by incorporating information across different biological scales—from molecular and cellular up to the organ, plant, and community levels.

Understanding the whole plant

Data for the system-level model was derived from soybean trials at University of Illinois South Farms. Image credit: Haley Ahlers.

The Crops in silico team at the University of Illinois and National Center for Supercomputing Applications is developing and linking models across different biological scales to more accurately simulate plant responses to a changing environment.

The team is developing models from the molecular to field, and root to leaf levels. Once the models are linked, an entire virtual crop canopy can be created and used to identify target genes for yield improvement under a range of environments. Other researchers can then use this information to develop crops that will thrive in tomorrow’s climate.

Crops in silico is currently focusing on soybean plants. The wealth of data from SoyFACE, an open-air experiment at the University of Illinois where soybean is grown in future climate conditions (e.g. elevated carbon dioxide, temperature, and drought), is facilitating model development and validation.

Rendered plant- and canopy-level data from the system-level model. Image credit: Crops in silico.

Future work by Crops in silico will target staple food crops in developing countries including rice, legumes, and cassava.

Crops in silico aims to create an open-source teaching and training tool for students. A user-friendly web interface will allow non-modelers to visualize model outputs as easy-to-interpret graphs, tables, animated simulations of plant growth and ecosystem interactions.

Building a research community

Photograph from the Plants in silico Symposium & Workshop held in Urbana, Illinois in 2016. Image credit: Rachel Shekar (Crops in silico).

The success of this effort is dependent on a connected Crops in silico community that can take full advantage of advances in computational science, and our mechanistic understanding of plant processes and their responses to the environment. The first step in creating the community was taken this summer when a group of international scientists met at the first Plants in silico Symposium & Workshop in Illinois. Workshop participants identified specific challenges to integrative and multi-scale modeling in plants, and their solutions.

Together, this community will create the most complete models of staple food crops, to identify varieties that will ensure food security around the world in the face of climate change.

For more information on the Plants in silico project, read the recent paper in Plant, Cell and Environment (open access): Plants in silico: why, why now and what?—an integrative platform for plant systems biology research.