Following on from last week’s post, Now That’s What I Call Plant Science 2015, we bring you a year in Plant Science!

January

The year began with a surprising paper that turned our understanding of the phytohormone auxin on its head. Researchers in China and the USA created Arabidopsis knockout mutants of AUXIN BINDING PROTEIN 1 (ABP1), expecting them to fail to respond to auxin and have developmental defects, as previously seen in the abp1-1 knockdown mutant. Instead, these plants were indistinguishable from wild type plants, leading the authors to conclude that ABP1 is not required for auxin signaling or Arabidopsis development as previously believed.

Read the paper in PNAS: Auxin binding protein 1 (ABP1) is not required for either auxin signaling or Arabidopsis development.

A paper later in the year from the same authors found that the embryonic lethality of the abp1-1 mutant is actually caused by the off-target linked deletion of the adjacent BSM gene.

Read this paper in Nature Plants: Embryonic lethality of Arabidopsis abp1-1 is caused by deletion of the adjacent BSM gene.

The tale of ABP1 was examined in more detail on the GARNet blog, Weeding the Gems, which concluded: “In many ways this story is an excellent example of how science should work, where claims are independently tested to ensure that earlier experiments have been conducted or interpreted correctly.” Click here to read more.

February

A clever experiment from Germany led to a significant breakthrough in crop protection from insect pests.

When double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is present within a eukaryotic cell, it is cleaved by the Dicer enzyme to form short interfering RNAs. These can bind to complementary RNA within a cell to target it for destruction, thus silencing the corresponding gene expression. This process is known as RNA interference (RNAi).

RNAi has previously been used to tackle insect herbivory by expressing insect-specific dsRNA in plants; however the protection has previously been incomplete. In this new study, published in Science, researchers produced dsRNA within chloroplasts, which do not have RNAi machinery. When dsRNA is expressed in the cytoplasm, the plant’s own Dicer enzyme breaks most of it down. When expressed in the chloroplasts, the dsRNA remained intact when eaten by insects, which proved much more effective at killing these pests.

Read the paper here: Full crop protection from an insect pest by expression of long double-stranded RNAs in plastids.

March

Another crop protection study followed in March, when researchers in China cloned the genetic locus in rice that confers broad-spectrum resistance to planthoppers – insect pests that cause the loss of billions of dollars of crops per year. Three lectin receptor kinase genes were found in rice cultivars from the Philippines, which enable plants to survive an infestation of insects. When cloned into a susceptible rice cultivar, these genes conferred resistance to two different planthopper species.

Understanding the genetic basis of resistance is very important as marker-assisted breeding and selection could be used to develop resistant rice varieties, and potentially utilized in other species of cereal.

Read the paper in Nature Biotechnology: A gene cluster encoding lectin receptor kinases confers broad-spectrum and durable insect resistance in rice

April

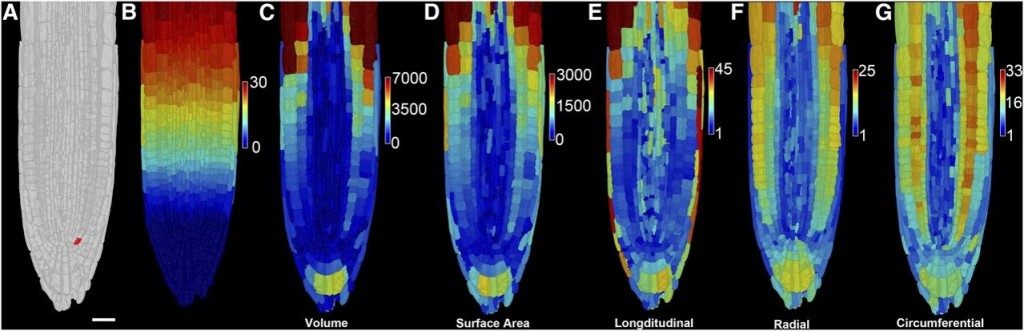

A European collaboration led to the development of 3DCellAtlas, a computational approach that semi-automatically identifies cell types in a developing 3D organ without the need for transgenic lineage markers. This program will enable the interpretation of dynamic organ growth and the spatial and temporal context of developmental cell divisions that produce the resultant plant. It could be integrated with growth in different conditions or with developmental mutants to examine exactly how these processes affect growth in 3D.

May

A special issue of the Plant Biotechnology Journal was published in May, focusing on the amazing advances in molecular farming. While the entire issue is worth delving into, we were particularly intrigued by the review on moss-made pharmaceuticals, which outlines the rapid progress made in the field.

The model moss Physcomitrella patens has rapidly become one of the organisms of choice in biotechnology, with a fully sequenced genome and an outstanding toolbox for genome-engineering. The authors describe how moss-made pharmaceuticals can easily be produced while remaining remarkably more stable from batch to batch than cultured animal cells. The system is easily scalable, making their production highly cost effective, and safe. The first moss-made pharmaceuticals are currently in clinical trials, so keep an eye out for much more from this field over the next few years.

Read the review: Moss-made pharmaceuticals: from bench to bedside.

June

In June, US researchers discovered a new role for chloroplast stromules, protrusions that extend from the surface of all plastid types. The function of stromules has been difficult to determine, but this research, published in Developmental Cell, suggests that they may provide a mechanism by which plastid signals are conveyed to the nucleus. The paper shows that chloroplast stromules are induced by defense responses such as programmed cell death signaling, and that the stromules extend to form dynamic connections with the nucleus. The stromules may therefore aid in the amplification and/or transport of immune response signals into the nucleus.

Read the paper: Chloroplast Stromules Function during Innate Immunity.

July

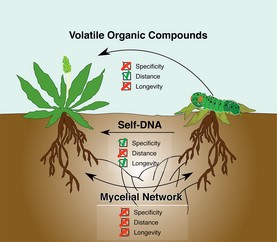

In late 2014 and early 2015, Italian researchers published a set of articles showing that extracellular self-DNA, DNA from conspecifics, could inhibit the growth of organisms from a wide range of taxa, including plants, bacteria, fungi and animals. Conversely, these organisms were not affected by extracellular DNA from other unrelated species.

In July, New Phytologist published a letter offering an interpretation of the data as it relates to plants. Plants could interpret extracellular self-DNA as an indicator of intraspecific competition (which seeds could use as a cue to remain dormant) or of a hostile environment that has already caused the death of conspecifics, signaling them to ramp up their pre-emptive immune response to increase survival after neighbors have been damaged or killed. There are still a lot of mechanisms and ecological effects to be investigated in this new field, but this letter suggests several interesting avenues to investigate.

Read the article: Self-DNA: a blessing in disguise?

Original research papers in New Phytologist:

Inhibitory and toxic effects of extracellular self-DNA in litter: a mechanism for negative plant–soil feedbacks?

Inhibitory effects of extracellular self-DNA: a general biological process?

August

A US study in August revealed a surprising degree of conservation in gene expression patterns across a wide range of plant taxa during root development. This was particularly interesting because the spikemoss Selaginella was shown to use many of the same genes as the evolutionarily distant angiosperms, despite the fossil record suggesting that roots evolved independently in these two lineages. Perhaps roots in these two groups evolved by independently recruiting the same developmental program, or perhaps by elaborating on a previously unknown proto-root that existed in the common ancestor of vascular plants.

Read the paper in The Plant Cell: Conserved Gene Expression Programs in Developing Roots from Diverse Plants.

September

Salt stress can significantly reduce the growth and yield of plants. Researchers in Germany identified two components of the cellulose synthase complex that directly interact with the microtubules and promote their dynamics, which interestingly were highly produced during salt stress conditions. During salt stress, cellulose microtubules depolymerize, however the newly discovered compounds, known as Companions of Cellulose Synthase, promote the reassembly of the microtubule to allow cellulose synthesis to continue.

Read the paper in Cell: A Mechanism for Sustained Cellulose Synthesis during Salt Stress

October

Throughout the year the GM debate in Europe reached several important milestones. In January the European Union (EU) changed its rules, giving individual countries more flexibility to decide for themselves whether or not to plant GM crops. In February, the UK Science and Technology Committee report stated that EU regulations preventing GM crops are not fit for purpose, and that they should be replaced with a trait-based system.

In October, EU member states revealed their stances on GM crops, with over half of Europe opting out of growing GM crops. Germany was the largest country to opt out of growing GM. The full list can be viewed here: Restrictions of geographical scope of GMO.

Read the news articles here:

EU changes rules on GM crop cultivation – January 2015

EU regulation on GM Organisms not ‘fit for purpose’ – February 2015

Half of Europe opts out of new GM crop scheme – October 2015

November

A collaboration between South African and UK scientists revealed how plants can use their circadian clock to pre-emptively boost their immune resistance at dawn, when fungal infection is most likely. Plants tend to decrease in susceptibility at dawn, but those with dysfunctional circadian clocks remained highly susceptible throughout the day. The research also showed that jasmonate signaling plays a crucial role in the circadian timing of resistance.

Read the article in The Plant Journal: Jasmonate signalling drives time-of-day differences in susceptibility of Arabidopsis to the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea.

December

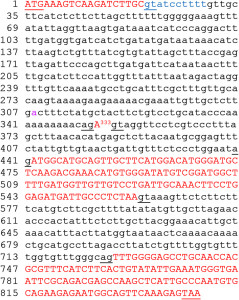

Researchers in China published the surprising finding that a single-nucleotide exon exists in the APC11 gene in Arabidopsis. This is the smallest exon ever to be discovered before. The team used an elegant set of APC11-GFP constructs to show that intron splicing around the single-nucleotide exon is effective in both Arabidopsis and rice. This finding has implications for future genome annotations, which might reveal many more single-nucleotide exons.

Read the paper in Scientific Reports: A single-nucleotide exon found in Arabidopsis.

What a wonderful year of science! What new knowledge will 2016 bring?