The Generation Challenge Programme (GCP – not to be confused with GPC!) was enthused about repeatedly during the three day GPC/SEB Stress Resilience Forum held in Iguassu Falls, Brazil. This 10-year program was created by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in 2003 as a collaborative approach to developing food crops with improved stress resilience, and is widely hailed as a very successful example of the benefits of international collaboration and practical targeted research funding.

Dr Jean-Marcel Ribault, director of the GCP, spoke at the meeting about the success of the $170 M program, and the key things that other projects should consider when designing collaborative partnerships.

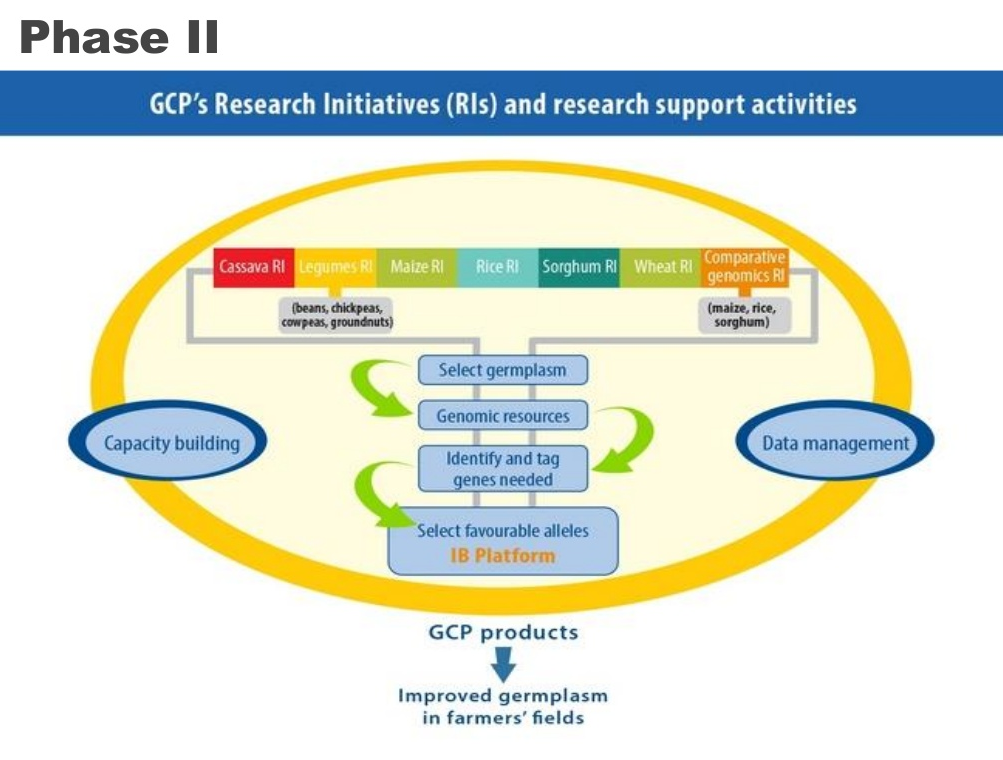

Research initiatives

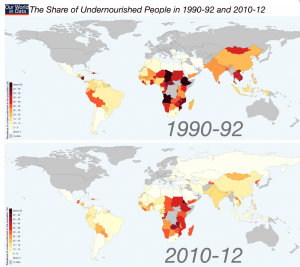

During its second phase (2009–2014), the GCP focused on seven key research initiatives: improving cassava, rice and sorghum for Africa’s drought-prone environments; improving drought tolerance in maize and wheat for Asia; tackling tropical legume productivity in marginal land in Africa and Asia; and the use of comparative genomics to improve cereal yields in high aluminum and low phosphorus soils.

The GCP acted as an international umbrella organization, distributing grants to fund research across different types of organizations (CG centers, universities and National Programs), either as commissioned projects or competitive funding calls. The aim was to bridge the gap between upstream research and applied crop science, enabling the development of markers and tools that could be of direct benefit to breeders and farmers in developing nations.

Ribault described one of the success stories of the GCP that highlighted the power of international collaborations working together on a problem to benefit people around the world. A team at Cornell University, working alongside Brazilian scientists, won a competitive grant to investigate aluminum (Al) tolerance in sorghum. They discovered a major gene responsible for Al tolerance by growing different accessions of sorghum in hydroponic systems, and began to breed tolerance into Brazilian sorghum cultivars through a commissioned project. The Brazilian team, with the support of scientists from Cornell, took on leadership to transfer these Al tolerant alleles to Africa, where they were also used to improve germplasm for Kenya and Niger.

An ongoing legacy of knowledge

The research funded by the GCP yielded many major research outputs, including a huge variety of genetic and genomic resources, improved germplasm and new bioinformatic tools to aid data management, diversity studies and breeding.

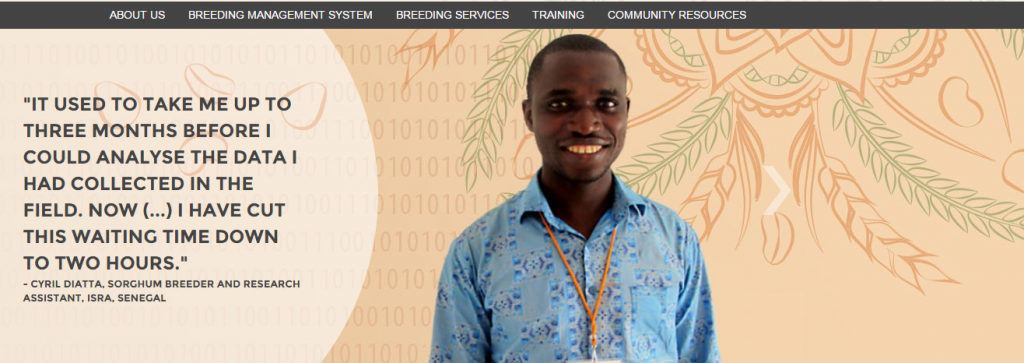

One of the most important parts of the GCP program was its support service component, a key part of which was the development of the Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP), an amazing resource for crop breeders. The IBP was designed as a way to disseminate knowledge and technology, giving breeders in developing countries access to the latest modern plant breeding tools and services in a practical manner.

The IBP’s core product, the Breeding Management System (BMS), allows breeders to manage their breeding program, including lists of crop genetic stocks as well as pedigree and germplasm information and field designs. It provides functionality for electronic phenotypic data capture and statistical analysis, access to molecular markers, breeding design and decision-support tools, and more. Through the Platform, users can also access climate data, geographic information system (GIS) information, genotyping services at concessionary prices, training opportunities and other relevant breeding support services.

A legacy of the GCP, the IBP lives on for further development and deployment, thanks to a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (phase II, 2014–2019). Ribault hinted that dissemination of the platform will be more difficult than its development; indeed it can be challenging to change a person’s behavior and work practices, even if breeders see the benefits of using the IBP!

The keys to success

Throughout his talk, Ribault described how the partnerships formed by and within the GCP were an important foundation to the success of the program. These dynamic networks were based on trust and on an evolution of responsibilities, and many of the partners have continued to work together after the GCP ended in 2014.

Working on projects around the world was not always easy, Ribault explained, but it meant that the results arising from the research were directly relevant to the agricultural practices in those countries, and therefore more likely to be used.

One of the most innovative approaches of the GCP was to dedicate around 15–20% of its budget each year to capacity development, which included holding workshops and training sessions, as well as funding studentships and fellowships to ensure future sustainability of the research projects. One novel practice was to run multi-year breeding courses, where participants were expected to bring along the outputs of their research each year. Anti-bottleneck funding was used to alleviate the problems that people were facing by providing much-needed resources or access to technology; Ribault highlighted this as one of the most important drivers of GCP’s success.

——

If you’d like to read more about the Generation Challenge Programme, please visit the GCP website.

If you’d like to read more about the Integrated Breeding Platform, please visit the IBP website.

The IBP is hosted on the cyberinfrastructure provided by the

The IBP is hosted on the cyberinfrastructure provided by the