The researchers found that farms with diverse crops planted together provide more secure, stable habitats for wildlife and are more resilient to climate change than the single-crop standard that dominates today’s agriculture industry.

The researchers found that farms with diverse crops planted together provide more secure, stable habitats for wildlife and are more resilient to climate change than the single-crop standard that dominates today’s agriculture industry.

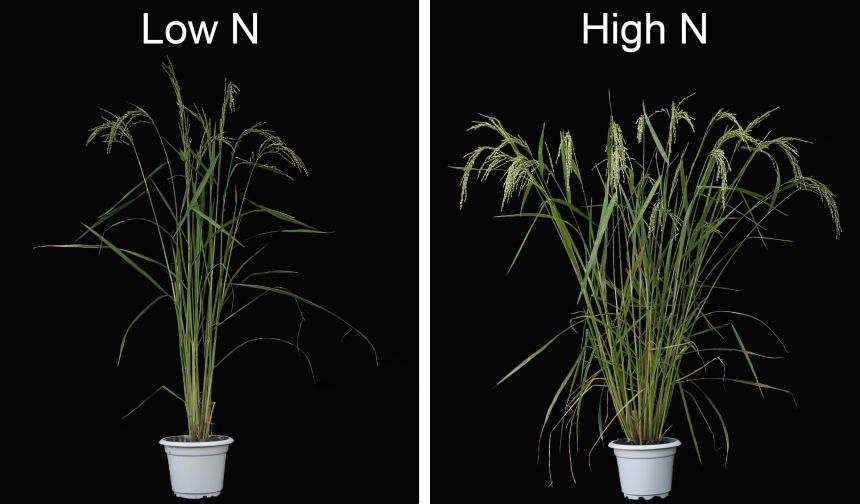

Researchers have discovered a new gene that improves the yield and fertilizer use efficiency of rice.

Scientists found benefits of insect leaf-wounding in fruit and vegetable production. Stress responses created in the fruits and vegetables initiated an increase in antioxidant compounds prior to harvest, which may make them healthier for human consumption.

What if we could grow plants that are larger and also have higher nutritional content? For decades, scientists have been trying to dial up amino acid content in crops by ramping up their production systems, but they always run into the same problem: the crops get sick. Until now.

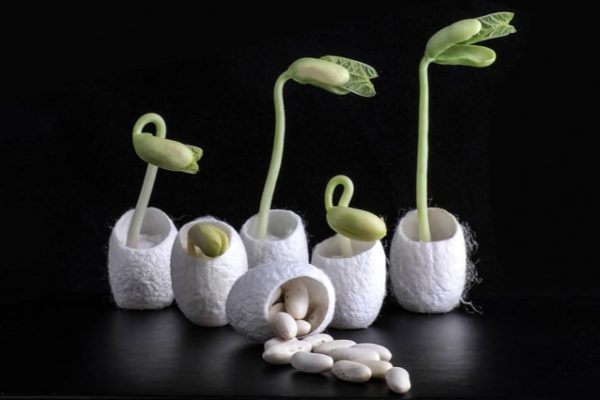

A specialized silk covering could protect seeds from salinity while also providing fertilizer-generating microbes.

By Atsuko Kanazawa, Igor Houwat, Cynthia Donovan

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

Atsuko Kanazawa is a plant scientist in the lab of David Kramer. Her main focus is on understanding the basics of photosynthesis, the process by which plants capture solar energy to generate our planet’s food supply.

This type of research has implications beyond academia, however, and the Kramer lab is using their knowledge, in addition to new technologies developed in their labs, to help farmers improve land management practices.

One component of the lab’s outreach efforts is its participation in the Legume Innovation Lab (LIL) at Michigan State University, a program which contributes to food security and economic growth in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

Atsuko recently joined a contingent that attended a LIL conference in Burkina Faso to discuss legume management with scientists from West Africa, Central America, Haiti, and the US. The experience was an eye opener, to say the least.

To understand some of the challenges faced by farmers in Africa, take a look at this picture, Atsuko says.

“When we look at corn fields in the Midwest, the corn stalks grow uniformly and are usually about the same height,” Atsuko says. “As you can see in this photo from Burkina Faso, their growth is not even.”

“Soil scientists tell us that much farmland in Africa suffers from poor nutrient content. In fact, farmers sometimes rely on finding a spot of good growth where animals have happened to fertilize the soil.”

Even if local farmers understand their problems, they often find that the appropriate solutions are beyond their reach. For example, items like fertilizer and pesticides are very expensive to buy.

That is where USAID’s Feed the Future and LIL step in, bringing economists, educators, nutritionists, and scientists to work with local universities, institutions, and private organizations towards designing best practices that improve farming and nutrition.

Atsuko says, “LIL works with local populations to select the most suitable crops for local conditions, improve soil quality, and manage pests and diseases in financially and environmentally sustainable ways.”

At the Burkina Faso conference, the Kramer lab reported how a team of US and Zambian researchers are mapping bean genes and identifying varieties that can sustainably grow in hot and drought conditions.

The team is relying on a new technology platform, called PhotosynQ, which has been designed and developed in the Kramer labs in Michigan.

PhotosynQ includes a hand-held instrument that can measure plant, soil, water, and environmental parameters. The device is relatively inexpensive and easy to use, which solves accessibility issues for communities with weak purchasing power.

The heart of PhotosynQ, however, is its open-source online platform, where users upload collected data so that it can be collaboratively analyzed among a community of 2400+ researchers, educators, and farmers from over 18 countries. The idea is to solve local problems through global collaboration.

Atsuko notes that the Zambia project’s focus on beans is part of the larger context under which USAID and LIL are functioning.

“From what I was told by other scientists, protein availability in diets tends to be a problem in developing countries, and that particularly affects children’s development,” Atsuko says. “Beans are cheaper than meat, and they are a good source of protein. Introducing high quality beans aims to improve nutrition quality.”

But, as LIL has found, good science and relationships don’t necessarily translate into new crops being embraced by local communities.

Farmers might be reluctant to try a new variety, because they don’t know how well it will perform or if it will cook well or taste good. They also worry that if a new crop is popular, they won’t have ready access to seed quantities that meet demand.

Sometimes, as Atsuko learned at the conference, the issue goes beyond farming or nutrition considerations. In one instance, local West African communities were reluctant to try out a bean variety suggested by LIL and its partners.

The issue was its color.

“One scientist reported that during a recent famine, West African countries imported cowpeas from their neighbors, and those beans had a similar color to the variety LIL was suggesting. So the reluctance was related to a memory from a bad time.”

This particular story does have a happy ending. LIL and the Burkina Faso governmental research agency, INERA, eventually suggested two varieties of cowpeas that were embraced by farmers. Their given names best translate as, “Hope,” and “Money,” perhaps as anticipation of the good life to come.

Another fruitful, perhaps more direct, approach of working with local communities has been supporting women-run cowpea seed and grain farms. These ventures are partnerships between LIL, the national research institute, private institutions, and Burkina Faso’s state and local governments.

Atsuko and other conference attendees visited two of these farms in person. The Women’s Association Yiye in Lago is a particularly impressive success story. Operating since 2009, it now includes 360 associated producing and processing groups, involving 5642 women and 40 men.

“They have been very active,” Atsuko remarks. “You name it: soil management, bean quality management, pest and disease control, and overall economic management, all these have been implemented by this consortium in a methodical fashion.”

“One of the local farm managers told our visiting group that their crop is wonderful, with high yield and good nutrition quality. Children are growing well, and their families can send them to good schools.”

As the numbers indicate, women are the main force behind the success. The reason is that, usually, men don’t do the fieldwork on cowpeas. “But that local farm manager said that now the farm is very successful, men were going to have to work harder and pitch in!”

Back in Michigan, Atsuko is back to the lab bench to continue her photosynthesis research. She still thinks about her Burkina Faso trip, especially how her participation in LIL’s collaborative framework facilitates the work she and her colleagues pursue in West Africa and other parts of the continent.

“We are very lucky to have technologies and knowledge that can be adapted by working with local populations. We ask them to tell us what they need, because they know what the real problems are, and then we jointly try to come up with tailored solutions.”

“It is a successful model, and I feel we are very privileged to be a part of our collaborators’ lives.”

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

This week we spoke to Dr. Joe Cornelius, the Program Director at the Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E). His work focusses on bioenergy production and conversion as a renewable and sustainable energy source, transportation fuel, and chemical feedstock, applying innovations in biotechnology, genomics, metabolic engineering, molecular breeding, computational analytics, remote sensing, and precision robotics to improve biomass energy density, production intensity, and environmental impacts.

This week we spoke to Dr. Joe Cornelius, the Program Director at the Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E). His work focusses on bioenergy production and conversion as a renewable and sustainable energy source, transportation fuel, and chemical feedstock, applying innovations in biotechnology, genomics, metabolic engineering, molecular breeding, computational analytics, remote sensing, and precision robotics to improve biomass energy density, production intensity, and environmental impacts.

What is ARPA-E? How are programs created?

The Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) is a young government agency in the U.S. Department of Energy. The agency is modeled on a successful Defense Department program, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Both agencies target high-risk, high-reward research in early-stage technologies that are not yet ready for private-sector investment.

Program development is one of the unique characteristics of the agency. ARPA-E projects are in the hands of term-limited program directors, who develop a broad portfolio of concepts that could make a large impact in the agency’s three primary mission areas: energy security, energy efficiency, and emissions reductions. The agency motto is “Changing what’s possible”, and we are always asking ourselves, “if it works, will it matter?”. Getting a program approved is a lot like a doing a PhD; you survey the field, host a workshop, determine key points to research, define aggressive performance metrics, and finally defend the idea to the faculty. If the idea passes muster, the agency makes a targeted investment. This flexibility was recently noticed as one of the great aspects of ARPA-E culture and is an exciting part of the job.

What is TERRA and how is it new for agriculture?

TERRA stands for Transportation Energy Resources from Renewable Agriculture, and its impact mission is to accelerate genetic gains in plant breeding. This is an advanced analytics platform for plant breeding. Today, significant scientific progress is possible through the convergence of diverse technologies, and TERRA’s innovation for breeders comes through the integration of remote sensing, computer vision, analytics, and genetics. The teams are using robots to carry cameras to the field and then extracting phenotypes and performing gene linkages. It’s really awesome to see.

This is run by the U.S. Department of Energy. How does TERRA tie into energy?

The United States has a great potential to generate biomass for conversion to cellulosic ethanol, but the crops useful for producing this biomass have not seen the improvement that others, such as soybeans or maize, have had. TERRA is focused on sorghum, which is a productive and resilient crop with existing commercial infrastructure that can yield advanced biomass on marginal lands. In addition, sorghum is a key food and feed crop, and the rest of the world will benefit from these advancements.

How does TERRA address the challenge of phenotyping in the field?

The real challenges that remain are in calibrating the sensor output and generating biological insight. A colleague from the United Kingdom, Tony Pridmore, captured the thought well, saying “Photography is not phenotying.” It’s generally easy to take the pictures — unless it’s very windy, the aerial platforms can pass over any crop, and the ground platforms are based on proven agricultural equipment. To get biological insights however, each team requires an analytics component, and a team from IBM is contributing their analytics expertise in collaboration with Purdue University.

What is most exciting about the TERRA program?

We commissioned the world’s biggest agricultural field robot, which phenotypes year-round. The six teams have successfully built other lightweight platforms involving tractors, rovers, mini-bots, and fixed and rotary wing unmanned aerial vehicles. It’s exciting to see some of the most advanced technologies move so quickly into the hands of great geneticists. The amazing thing is how quickly the teams have started generating phenotyping data. I expected it to take years before we got to this point, but the teams are knocking it out of the park, and we are entering into full-blown breeding systems deployment.

Who’s on the TERRA teams? How did you build the program?

ARPA-E system teams include large businesses, startups, and university groups. The program was built to have a full portfolio of diverse sensor suites, robotic platform types (ground and aerial), analytics approaches, and geographic breadth. Because breeders are working for a particular target population of environments, different phenotypes are valued differently across the various geographies. For that reason, each group is collecting its own set of phenotypes. Beyond that, we’ve worked very hard to encourage collaboration across the teams and have an exciting GxE (genotype x environment) experiment running, where several teams plant the same germplasm across multiple geographies. By combining this with high-throughput phenotyping, the teams are in a good position to determine key environmental inputs to various traits.

Once we achieve rapid-fire field phenotyping, what’s next?

We’re going underground! ARPA-E has made another targeted investment, this time in root phenotyping. We’re really excited about this one. It’s a very similar concept, but the sensing is so much harder. The teams have collaborated with medical, mining, aerospace, and defense communities for technologies that can allow us to observe root and soil systems in the field to allow breeders to improve crops. Ask us again next year—we will have some cool updates to both programs!

Reposted with kind permission from the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory. Original article.

The need for speed: increasing plant yield is one way to increase food and fuel resources. But asking plants to simply do more of the usual is a strategy that can backfire. Photo by Romain Peli on Unsplash

When engineers want to speed something up, they look for the “pinch points”, the slowest steps in a system, and make them faster.

Say, you want more water to flow through your plumbing. You’d find the narrowest pipe and replace it with a bigger one.

Many labs are attempting this method with photosynthesis, the process that plants and algae use to capture solar energy.

All of our food and most of our fuels have come from photosynthesis. As our population increases, we need more food and fuel, requiring that we improve the efficiency of photosynthesis.

But, Dr. Atsuko Kanazawa and the Kramer Lab are finding that, for biological systems, the “pinch point” method can potentially do more harm than good, because the pinch points are there for a reason! So, how can this be done?

Atsuko and her colleagues at the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory (PRL) have been working on this problem for over 15 years. They have focused on a tiny machine in the chloroplast called the ATP synthase, a complex of proteins essential to storing solar energy in “high energy molecules” that power life on Earth.

That same ATP molecule and a very similar ATP synthase are both used by animals, including humans, to grow, maintain health, and move.

In plants, the ATP synthase happens to be one of the slowest process in photosynthesis, often limiting the amount of energy plants can store.

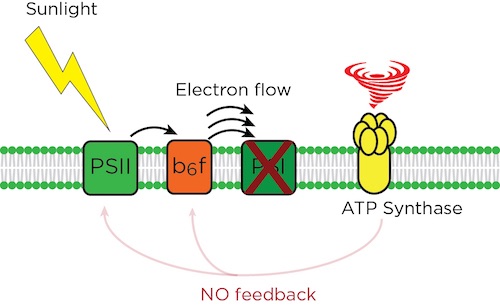

Photosynthetic systems trap sunlight energy that starts the reaction to move electrons forward in an assembly-line fashion to make useful energy compounds. The ATP synthase is one of the “pinch points” that slows the flow as needed, so plants stay healthy. In cfq, the absence of feedback leads to an electron pile up at PSI, and a crashed system. By MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory, except tornado graphic/CC0 Creative Commons

Atsuko thought, if the ATP synthase is such an important pinch point, what happens if it were faster? Would it be better at photosynthesis and give us faster growing plants?

Years ago, she got her hands on a mutant plant, called cfq, from a colleague. “It had an ATP synthase that worked non-stop, without slowing down, which was a curious example to investigate. In fact, under controlled laboratory conditions – very mild and steady light, temperature, and water conditions – this mutant plant grew bigger than its wild cousin.”

But when the researchers grew the plant under the more varied conditions it experiences in real life, it suffered serious damage, nearly dying.

“In nature, light and temperature quality change all the time, whether through the passing hours, or the presence of cloud cover or winds that blow through the leaves,” she says.

Atsuko’s research now shows that the slowness of the ATP synthase is not an accident; it’s an important braking mechanism that prevents photosynthesis from producing harmful chemicals, called reactive oxygen species, which can damage or kill the plant.

“It turns out that sunlight can be damaging to plants,” says Dave Kramer, Hannah Distinguished Professor and lead investigator in the Kramer lab.

“When plants cannot use the light energy they are capturing, photosynthesis backs up and toxic chemicals accumulate, potentially destroying parts of the photosynthetic system. It is especially dangerous when light and other conditions, like temperature, change rapidly.”

“We need to figure out how the plant presses on the brakes and tune it so that it responds faster…”

The ATP synthase senses these changes and slows down light capture to prevent damage. In that light, the cfqmutant’s fast ATP is a bad idea for the plant’s well-being.

“It’s as if I promised to make your car run faster by removing the brakes. In fact, it would work, but only for a short while. Then things go very wrong!” Dave says.

“In order to improve photosynthesis, what we need is not to remove the brakes completely, like in cfq, but to control them better,” Dave says. “Specifically, we need to figure out how the plant presses on the brakes and tune it so that it responds faster and more efficiently,” David says.

Atsuko adds: “Scientists are trying different methods to improve photosynthesis. Ultimately, we all want to tackle some long-term problems. Crucially, we need to continue feeding the Earth’s population, which is exploding in size.”

The study is published in the journal, Frontiers in Plant Science.

A scenario starring the root crop was portrayed in the movie “The Martian” (2015), in which a lost astronaut, played by Matt Damon, survives on potatoes he cultivates on the red planet while awaiting rescue.

But in addition to this interplanetary possibility, scientists also observed the crop is genetically suited to adapting to the changes creating more adverse environmental conditions on Earth.

So before turning fiction into reality, the tuber has a mission on Earth.

The study has identified four types of potatoes, out of 65 examined, which have shown resistance to high salinity conditions and were able to form tubers in a type of soil similar to that on Mars.

One of these is the Tacna variety, developed in Peru in 1993. It was introduced to China shortly afterwards, where it showed high tolerance to droughts and saline soils with hardly any need for irrigation.

This variety became so popular in China that it was ‘adopted’ in 2006 under the name of Jizhangshu 8. The same high tolerance was seen on the saline and arid soils of Uzbekistan, a country with high temperatures and water shortages, where the variety was also introduced and renamed as Pskom.

The second variety that passed the salinity test is being cultivated in coastal areas of Bangladesh that have high salinity soils and high temperatures. The other two types are promising clones — potatoes that are being tested for attributes that would make them candidates for becoming new varieties.

These four potato types were created as a result of the CIP’s breeding programme to encourage adaptation to conditions in subtropical lowlands, such as extreme temperatures, which are expected to be strongly affected by climate change.

Down to Earth

In addition to these four potato ‘finalists’, other clones and varieties have shown promising results when tested in severe environmental conditions. The findings offer researchers new clues about the genetic traits that can help tubers cope with severe weather scenarios on Earth.

“It was a pleasant surprise to see that the potatoes that we have improved to tolerate adverse conditions were able to produce tubers on this soil [soil similar to that on Mars],” says Walter Amorós, CIP potato breeder and one of the five researchers involved in the project, who has studied potatoes for more than 30 years.

According to Alberto García, adviser to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in Peru who is in charge of food security programmes, this experiment “serves to verify that potato, a produce of great nutritional value, is a crop extremely adaptable to the worst conditions”, something that is very relevant for current climate scenarios.

García stresses that global temperatures are now rising at a rate higher than expected, affecting not only potatoes but also other crops. Many now need to be cultivated at higher altitudes — which, he says, is not always a disadvantage and may even be beneficial for crops that were previously cultivated in valleys.

“But it can also have negative consequences that we have to anticipate,” adds García. Therefore, he says this experiment can inspire others to think about future scenarios and look for other crops than can adapt to extreme conditions that will have an impact on agriculture.

The project began with a search for soils similar to that found on Mars. Julio Valdivia-Silva, a Peruvian researcher who worked at NASA’s Ames Research Center, eventually concluded that the soil samples collected in the Pampas de la Joya region of southern Peru were the most similar to Martian soil.

Arid, sterile and formed by volcanic rocks, these soil samples were extremely saline.

Helped by engineers from the University of Engineering and Technology (UTEC) in Lima and based on designs by NASA’s Ames Research Center, the CIP built CubeSat — a miniature satellite that recreates, in a confined environment, a Martian-like atmosphere. This is where the potatoes were cultivated.

“If potatoes could tolerate the extreme conditions to which we exposed them in our CubeSat, they have a good opportunity to develop on Mars,” says Valdivia-Silva.

They then conducted several rounds of experiments to find out which varieties could better withstand the extreme conditions, and what minimum conditions each crop needed to survive.

CubeSat, hermetically sealed, housed a container with La Joya soil, where each one of the tubers was cultivated. CubeSat itself supplied water and nutrients, controlled the temperature according to that expected at different times on Mars, and also regulated the planet’s pressure, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels.

Cameras were installed to record the process, broadcasting developments on the soil and making it possible to see the precise moment in which potatoes sprouted.

Based on the results, CIP scientists say that in order to grow potatoes on Mars, space missions will have to prepare the soil so it has a loose structure and contains nutrients that allow the tubers to obtain enough oxygen and water.

In a next phase of the project, the scientists hope to expose successful varieties to more extreme environmental conditions. This requires, among other things, developing a prototype satellite similar to CubeSat that can replicate more extreme conditions with greater precision, at a price tag of US$ 100,000.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Latin America and Caribbean desk.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.

This week’s post was written by Dr Ian Street (@IHStreet), the Resources Editor at AoB Blog. He is also a science writer and plant scientist. His science blog is The Quiet Branches.

On 18th May 2017, plant scientists from all over the world celebrated “International Fascination of Plants Day”. This year, plant enthusiasts could follow events around the world – thanks to social media and live-streaming. Scientists shared live broadcasts about the science they do, the facilities where they work, models from history, about engaging students with plants, and more. Botany Live, organized by the AoB Blog, was an experiment in science engagement supported by the Society for Experimental Biology, The Annals of Botany Company, and Plantae. Overall, thousands tuned in to 31 planned events registered with Botany Live.

Using Periscope and Facebook Live, some reported from dedicated events planned around Plant Day. Others talked directly to the camera and their virtual audience about plants, plant science, and communicating plant science.

The Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) at Ohio State University showed off the facilities and robots they use to maintain both gene stocks and seed stocks. These facilities and resources, which provide essential support for plant research, are often only known within the plant science community. Even there, how they operate on a day-to-day basis remains a mystery to many. Botany Live allowed us to take a peek at the support structures that make international plant science possible. The ABRC videos also showed how plant science is using cutting edge technology with robots to automate seed sorting and gene stocks.

Frame from the Hounsfield Facility Botany Live Broadcast, showing the glass house and the robot that carries individual plants to be scanned.

A tour of the Hounsfield X-ray Facility (@UoNHounsfield) demonstrated the high-tech nature of modern plant science too. The staging the Hounsfield video was clever, as the scientists there clearly set up marks they had to hit to be on camera at certain times demonstrating the three sizes of scanner at the facility. Their live-stream ended with Malcolm Bennett in the glass house talking about the importance of exploring root traits, a big part of what they track at Hounsfield with robots and 3D X-ray tomography.

The National Institute of Agricultural Botany (NIAB) wheat transformation facility broadcast brought us cutting-edge biology directly from the field. Alison Bentley (@AlisonRBentley) guiding us around the facility, where scientists develop and field test new varieties of wheat, followed by a look around their glasshouses. Geraint Parry (@GARNetweets) then interviewed several NIAB conference attendees. A specialized facility for wheat transformation (making transgenic wheat) is, like the ABRC and Hounsfield, a resource of a special capacity to do something technical that not all individual labs can develop.

An infected plant in background and flower in the foreground from Monica Lewandowski’s Botany Live Broadcast.

Another outdoor tour of a garden in California was given by Monica Lewandowski. She highlighted the diversity of plants grown in the state’s central valley. She also spoke about some of the challenges that plants face, and why we need plant scientists to study them. It showed the simplicity possible with Periscope broadcasts, as her session focused on just her with planned talking points, a walking path, and her voice-over.

Alun Salt of the AoB Blog brought us some short broadcasts from Kew Gardens. He gave a brief tour of the Wollemi pine, an ancient lineage known only from fossils until 1994. He also gave a quick overview of the garden’s carnivorous plants, including the coolest plant in the world, Darlingtonia californica.

Several Botany Live recordings involved school students. Alistair Culham and Dr M (@drmgoeswild) broadcast a video with students about what they’d done earlier, counting plants and observing them. Many of the students were surprised to learn where pineapples come from: not from a tree, but a bush yielding a single pineapple a year. The Gramene Database (@GrameneDatabase) broadcast a talk with students about plants’ superpowers such as resurrection plants, which can lose 95% of their water and seemingly come back to life upon rehydration. Maria Papanatsiou (@m_papanatsiou) from the University of Glasgow broadcast Plant Day activities engaging students, and many of the videos can be found on the social wall of tweets made for Botany Live.

The most popular Plant Day broadcast was from the Manchester Museum, featuring botany curators Rachel Webster (Manchester) and Donna Young (Liverpool) talking about Brendel’s Plant Models collections from Manchester and the Liverpool World Museum. They’re remarkable models of plants, made of paper mache amongst other materials, created in 1880-1920 by a father/son team in Germany. They were designed to teach plant anatomy and many are incredibly intricate, with some even being able to be taken apart to show specific parts of a flower.

Brendel Plant Model Nr. 10, Pisum Sativum: Accreditation: By David Ludwig (own work at Botanical Museum in Greifswald) Image credit: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Botany Live broadcasts came from all over the world, and the event can grow in the years to come. The format of live streaming is flexible, with elaborate or simple setups possible. Most broadcasts were under ten minutes, but some lasted almost an hour, and of course, they can be done nearly anytime and anywhere with a good data connection.

This first year of Botany Live was an experiment. With thousands of people reached (and likely more, as many of the videos are still available), it was a success and a boost to the Plant Day events already taking place, extending their reach online. Given the success the Manchester Museum had with their broadcast, more institutions being directly involved will help promote the live broadcasts and engage even more people in the fascinating world of plants.

Further reading:

GARNet newsletter also covered Botany Live in its May 2017 issue (pdf)