Last week’s board meeting was incredible. That’s not something you normally hear after a meeting! What really struck me was just how global the Global Plant Council now is. The Board consists of representatives from 10 different countries on 5 continents (Chile, Mexico, Canada, UK, Spain, India, Italy, China, Japan and Australia). Every one of us at that meeting was in some kind of lockdown. I was overwhelmed with just how connected we all are. It was quite emotional.

All of humanity is in this pandemic together. But we are also all connected through nature: the atmosphere with rising CO2 changing our climate; the heartbreaking destruction of habitats around the world; and our need to grow and distribute enough food to feed everyone. These things are not independent from one another. There is increasing evidence that zoonotic diseases, like COVID-19, HIV-AIDS and SARS-1, are more likely to arise where habitat destruction leads to the increasing juxtaposition of people and wild animals.

This pandemic should be a wake-up call. Sustainability is not only important, it is essential. Ecosystems need to be conserved, not just because they have a right to be preserved for their own sakes, but for the health and well-being of the human population. It is arrogant of humans to think we can do whatever we like with nature. Right now, nature is coming back to bite us.

Plants around the world are being driven to extinction by excessive use of resources, land clearing and climate change. We don’t even know how many plants there are in the world. At the most basic level, we may be losing plants with unique chemicals that could be used to cure diseases, unique genotypes of crop wild relatives that could be a source of traits to improve agricultural productivity and so on.

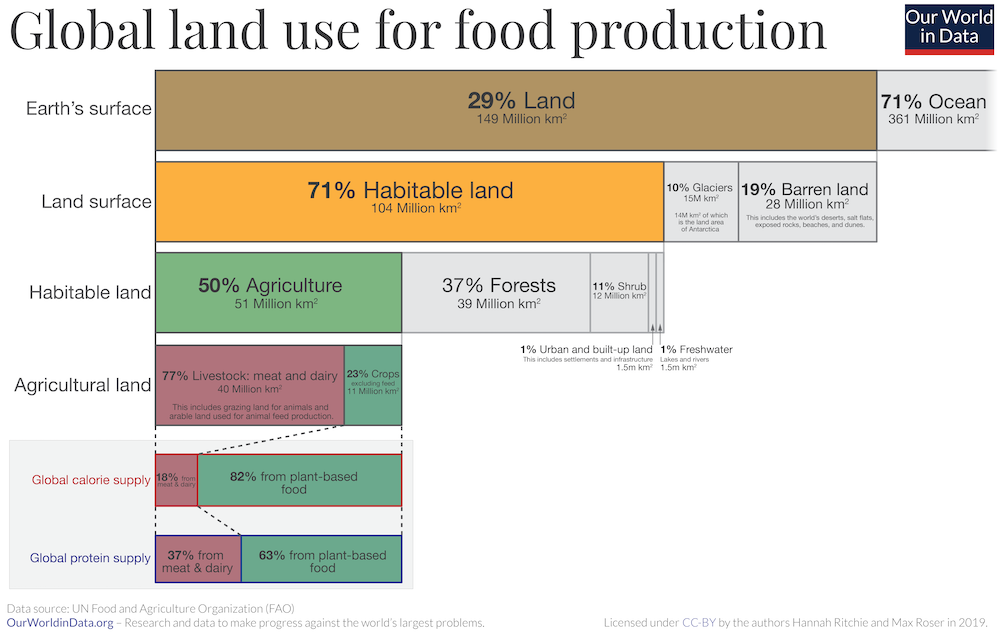

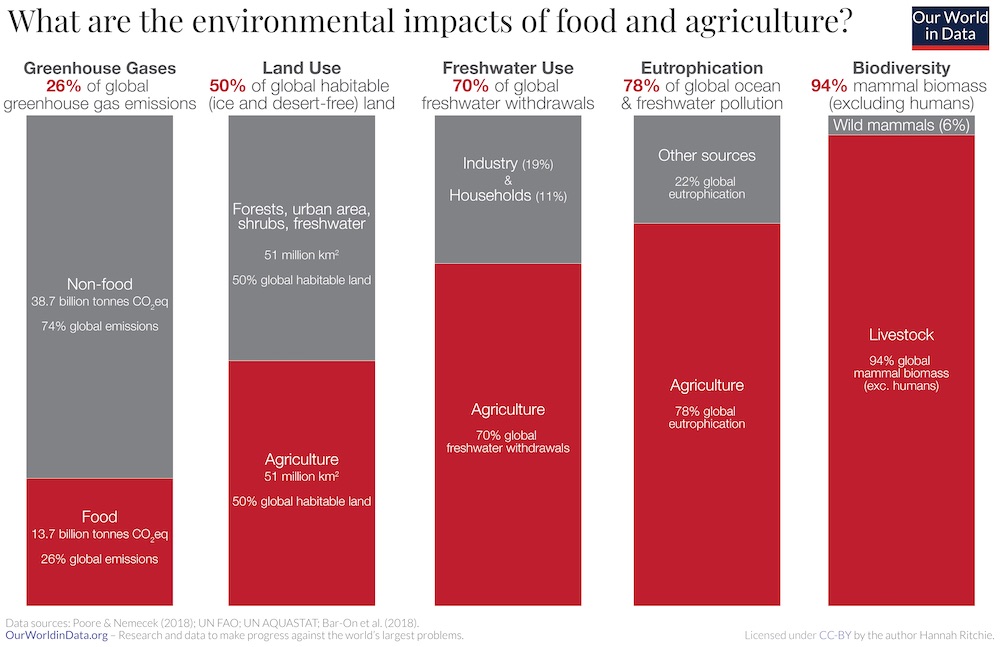

Agriculture is responsible for 26% of global greenhouse gases emissions, 70% of the freshwater use and occupies 50% of the habitable land surface. Plant scientists around the world are working to document species diversity, design conservation reserves, collect seeds for storage in seed banks, develop more efficient crops that use less fertiliser and water and are resistant to pests and diseases without the need for the application of large volumes of agrichemicals.

The Global Plant Council aims to increase the awareness plants, of the need to train plant scientists and to supply them with research funding. It seems crazy that we have to say this, but with a world inflicted with plant blindness, our first job is to get people to just open their eyes and see the plants around them and the central role they play. Just having an organisation called The Global Plant Council enables journalists and influencers to identify people to contact for comment in different countries. This is one reason why we are so keen to have representatives from all countries and from many different plant science organisations around the world.

In the past two years we have grown our social media presence by 50% percent annually, largely due to the efforts of our Chief Communications Officer, Dr Isabel Mendoza (currently locked down in Valencia, Spain). We are also expanding into different languages with a Spanish Twitter account and a new Weibo account to reach our Chinese followers. English maybe the current international language of science but if we want to reach people across the world, we need to communicate in different languages and on different platforms.

At this years’ GPC annual meeting we were planning to run a workshop on science communication with a special workshop run by the award-winning Italian science journalist Michele Catanzaro. We always hold our meetings in conjunction with a larger plant science conference, rotating around the world – last year it was at the ICAR meeting in Wuhan, and this year we planned to meet in Torino, Italy at Plant Biology Europe 2020. The conference has, of course, been postponed due to the raging pandemic. We really hope we can hold this fantastic workshop one way next year.

The annual business meeting this year will still need to be held and we will do that virtually. This is not easy given all the different time zones, but instead of an imposition, we should instead celebrate that the GPC is now truly global. The Era we live in, the Holocene, is characterised by possibly the highest biodiversity in the history of our planet. As we move into the Anthropocene, that is changing. Let’s work together to minimize the damage. It’s not going to be easy, but without plants, it’s impossible.

Author: Prof. Ros Gleadow, President of The Global Plant Council

Image credit: Free-Photos / Pixabay

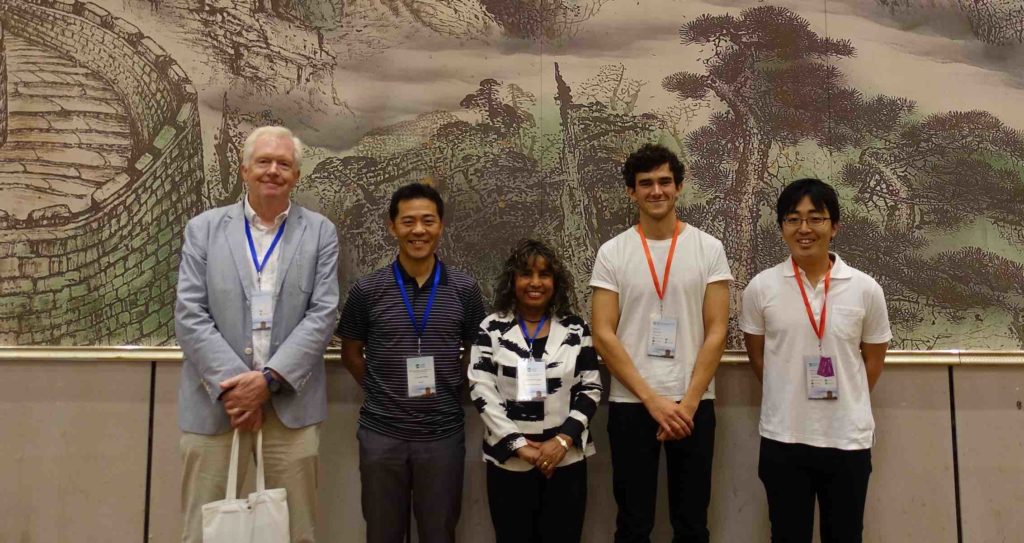

GPC annual meeting group picture. From left to right: Xuelu Wang (ICAR2019 organizer); Weihua Tang (China Society Plant Biology); Blake Meyers (Danforth Center); Deena Errampalli (GPC Board of Directors Treasurer, President, Plant Canada); Bill Davies (GPC Past-President, UK Plant Sciences Federation); Isabel Mendoza (GPC communications officer); Barry Pogson (GPC chair, Australian Society of Plant Scientists); Geraint Parry (SEB, MASC) and Rodrigo Gutierrez (Chilean Society of Plant Biology)

One of the Global Plant Council’s (GPC) principal objectives is to reach the global plant science audience. And to pursue this aim, the GPC annual meeting is held every year in parallel to a big plant science conference.

In accordance with this practice, the GPC took its annual meeting this June to the 30th International Conference on Arabidopsis Research (ICAR2019). This international conference was held on June 16-21, 2019 in Wuhan, China and attended by over 1,000 plant scientists from around the world.

GPC also took an active part in the conference itself hosting two of the offered workshops. Understandably, many members of GPC board were there, either as invited speakers (Barry Pogson, GPC Chair); or as part of the workshops organizing team (Bill Davies, GPC past-president; Deena Errampalli, GPC treasurer; Yosuke Saijo (Board Member) and Isabel Mendoza (GPC communications officer).

The first workshop “Role of the microbiome in sustainable agriculture” was held on the 18th June. Led by Deena Errampalli and Yosuke Saijo and with the participation from Bill Davies, Ruben Garrido-Oter and Kei Hiruma. Over 40 people attended the workshop, which provided participants with up-to-date knowledge on the role of the microbiome in Arabidopsis and its application on sustainable agriculture. Practical cases such as the Canadian ginseng were also introduced.

On the 19th June, the GPC team held the second of these workshops “Communicating your science to the broader community” addressed especially for early career researchers. Over 45 people attended. This meeting was led by Isabel Mendoza with the cooperation of Mary Williams (@PlantTeaching) and Geraint Parry (@GARNetweets). The meeting provided participants with clues on how to increase the impact of their own research, helping them understand the rules of science communication and tricks on how to profit from the more commonly used online channels.

This was the first dissemination activity of the recently established Early Career Researcher International (ECRi) network, an initiative that aims to help the ECRs in developing their careers. A dedicated post on the issues discussed at the workshop is on development. Stay tuned!

By Mathew Reynolds, Wheat Physiologist at, CIMMYT

First post of our “Global Collaboration” series

Wheat is the most widely grown crop in the world, currently providing about 20 percent of human calorie consumption. However, demand is predicted to increase by 60 percent within just 30 years, while long-term climate trends threaten to reduce wheat productivity, especially in less developed countries.

For over half a century, the International Wheat Improvement Network (IWIN), coordinated by CIMMYT, has been a global leader in breeding and disseminating improved wheat varieties to combat this problem, with a major focus on the constraints of resource poor farmers.

Two complementary networks — the Heat and Drought Wheat Improvement Consortium (HeDWIC) and the International Wheat Yield Partnership (IWYP) — are helping to meet the future demand for wheat consumption through global collaboration and technological partnership.

By harnessing the latest technologies in crop physiology, genetics and breeding, network researchers support the development of new varieties that aim to be more climate resilient, in the case of HeDWIC and with higher yield potential, in the case of IWYP.

These novel approaches to collaboration take wheat research from the theoretical to the practical and incorporate science into real-life breeding scenarios. Methods such as screening genetic resources for physiological traits related to radiation use efficiency and identifying common genetic bases for heat and drought adaptation are leading to more precise breeding strategies and more data for models of genotype-by-environment interaction that help build new plant types and experimental environments for future climates.

IWYP addresses the challenge of raising the genetic wheat yield potential of wheat by up to 50 percent in the next two decades. Achieving this goal requires a strategic and collaborative approach to enable the best scientific teams from across the globe to work together in an integrated program. TheIWYP model of collaboration fosters linkages between ongoing research platforms to develop a cohesive portfolio of activities that maximizes the probability of impact in farmers’ fields IWYP research uses genomic selection to complement the crossing of complex traits by identifying favorable allele combinations among progeny. The resulting products are delivered to national wheat programs worldwide through the IWIN international nursery system.

Recently, IWYP research achieved genetic gains through the strategic crossing of biomass and harvest index — source and sink — an approach that also validates the feasibility of incorporating exotic germplasm into mainstream breeding efforts.

In the case of HeDWIC, intensified — and possibly new — breeding strategies are needed to improve the yield potential of wheat in hotter and drier environments. This also requires a combined effort, using genetic diversity with physiological and molecular breeding and bioinformatic technologies, along with the adoption of improved agronomic practices by farmers. The approach already has proof of concept in the release and adoption of three heat and drought tolerant lines in Pakistan.

It is imperative to build increased yield and climate-resilience to into future germplasm in order to avoid the risk of climate-related crop failure and to maintain global food security in a warmer climate. Partnerships like HeDWIC and IWYP give hope to meeting this urgent food security challenge.

Further readings:

https://www.hedwic.org/resources.htm

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2012.2190

An economist’s perspective on plant sciences: Under-appreciated, over-regulated and under-funded

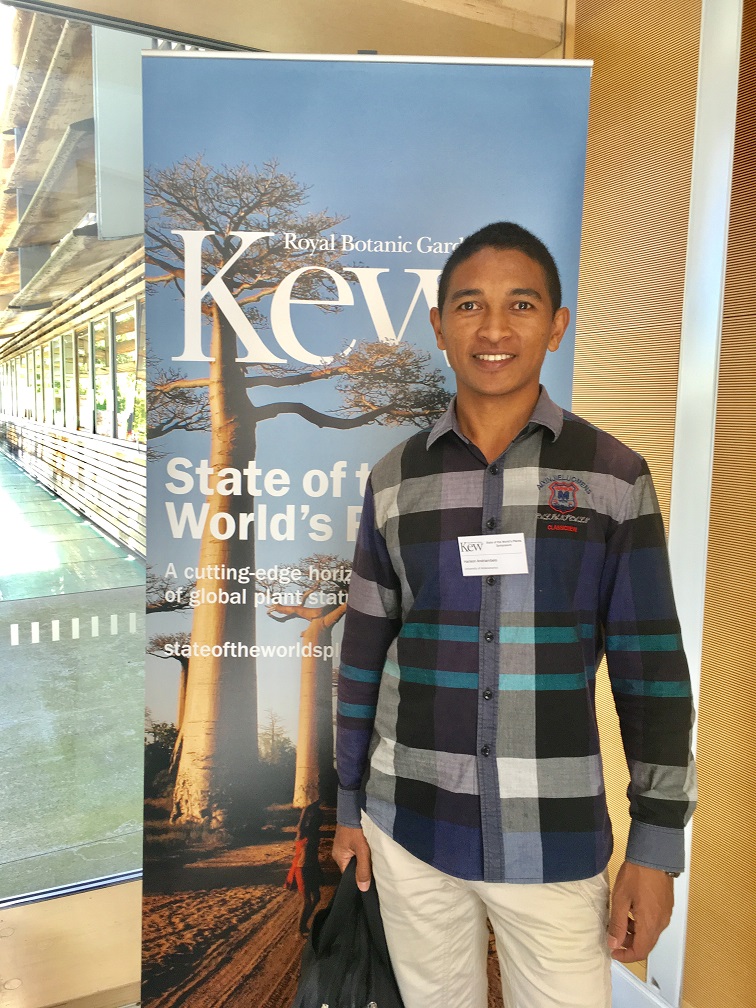

This week’s post was written by Harison Andriambelo, a PhD student at the University of Antananarivo, Madagascar. Harison was the awardee of the Early Career Researcher travel bursary from the Society for Experimental Biology in association with the Global Plant Council, enabling him to attend the State of the World’s Plants Symposium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Here’s how he got on!

This week’s post was written by Harison Andriambelo, a PhD student at the University of Antananarivo, Madagascar. Harison was the awardee of the Early Career Researcher travel bursary from the Society for Experimental Biology in association with the Global Plant Council, enabling him to attend the State of the World’s Plants Symposium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Here’s how he got on!

Attending the State of the World’s Plants Symposium 2017 at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, was a fantastic opportunity for me to get a detailed insight into many aspects of plant conservation, including the latest emerging research. Scientists from all over the world attended the symposium and shared results from several ecoregions, including tropical, boreal, and temperate biomes. It was also great to visit the Gardens, which were looking amazing in the British summertime.

As a botanist from Madagascar, I found the focus session on conservation in my country particularly useful, and I really enjoyed the talks by Pete Lowry and George Schatz, both from Missouri Botanic Garden.

Other sessions in the conference highlighted important issues including fires and invasive species. We heard that fire is not always bad for plants, especially in savannah systems, where plant diversity is maintained by the fire regime. I believe better scientific communication to the public is urgently needed on this issue.

Another great session concerned invasive species. I have worked across all the biomes in Madagascar, from humid forests to the dry spiny forest, and I have seen first-hand the effects invasive plants can have. A detailed assessment of invasive plant species in wetlands and in the western dry forests of Madagascar made me more aware of the potential impacts of these species. By attending this symposium, I learned about several programs and efforts by the Invasive Species Specialist Group and will spread information about invasive species management to colleagues once I return to Madagascar.

Another great session concerned invasive species. I have worked across all the biomes in Madagascar, from humid forests to the dry spiny forest, and I have seen first-hand the effects invasive plants can have. A detailed assessment of invasive plant species in wetlands and in the western dry forests of Madagascar made me more aware of the potential impacts of these species. By attending this symposium, I learned about several programs and efforts by the Invasive Species Specialist Group and will spread information about invasive species management to colleagues once I return to Madagascar.

For me, the highlight of the session on medicinal plants was a talk by the President of Mauritius. It was inspirational to see that scientists can even become a head of state. Such leadership offers great promise for addressing environmental issues at national scale. I am certain that having an ecologist as President in Madagascar would allow much greater progress on conservation issues in my home country, which has many highly threatened endemic species. Scientists can bring their understanding and ability to analyze complex systems to bear on policy. Good leaders can take a long-term holistic view and accord the appropriate priority to the environment in national plans for development.

This symposium allowed me to present some results of my research activities in Madagascar and get feedback from an international group of scientists. A deep discussion with people working at RBG Kew about how to scale information on tree dispersal processes from the plot to landscape scales was very valuable. As they know the Madagascan context, they were very interested in my results and a possible collaboration is on its way.

Finally, this trip to London allowed me to spend more time with my colleague Dr Peter Long at the University of Oxford and to make good progress for my scientific research activities. I am very grateful to the Society for Experimental Biology for supporting my travel to the UK to participate in this meeting.

This week we spoke to Francisco Gomez and Ammani Kyanam, graduate students in the Soil and Crop Science Department at Texas A&M University, USA. They were part of the organizing committee for the recent Texas A&M Plant Breeding Symposium, a successful meeting run entirely by students at the University.

Francisco Gomez and Ammani Kyanam, part of the student organizing committee of the Plant Breeding Symposium

Could you begin with a brief introduction to the Plant Breeding Symposium held at Texas A&M in February?

Texas A&M University is one of the largest academic and public plant breeding institutions worldwide, which trains breeders in a variety of programs. Every year, students at the University organize the Texas A&M Plant Breeding Symposium, which is part of the DuPont Pioneer series of symposia. The symposium provides a platform for graduate students to bridge the interaction between the public and private sectors and engage in conversations about the grand challenges facing humanity that could be addressed by plant breeding. It’s also a great chance to network with faculty, students, and industry representatives.

Could you tell us more about this theme and how the different sessions were chosen?

We wanted the theme of the meeting to mirror the university’s goal of thinking big to pinpoint solutions to modern global challenges using plant science and breeding. Every member of the committee had the opportunity propose a theme, which were then put to a vote.

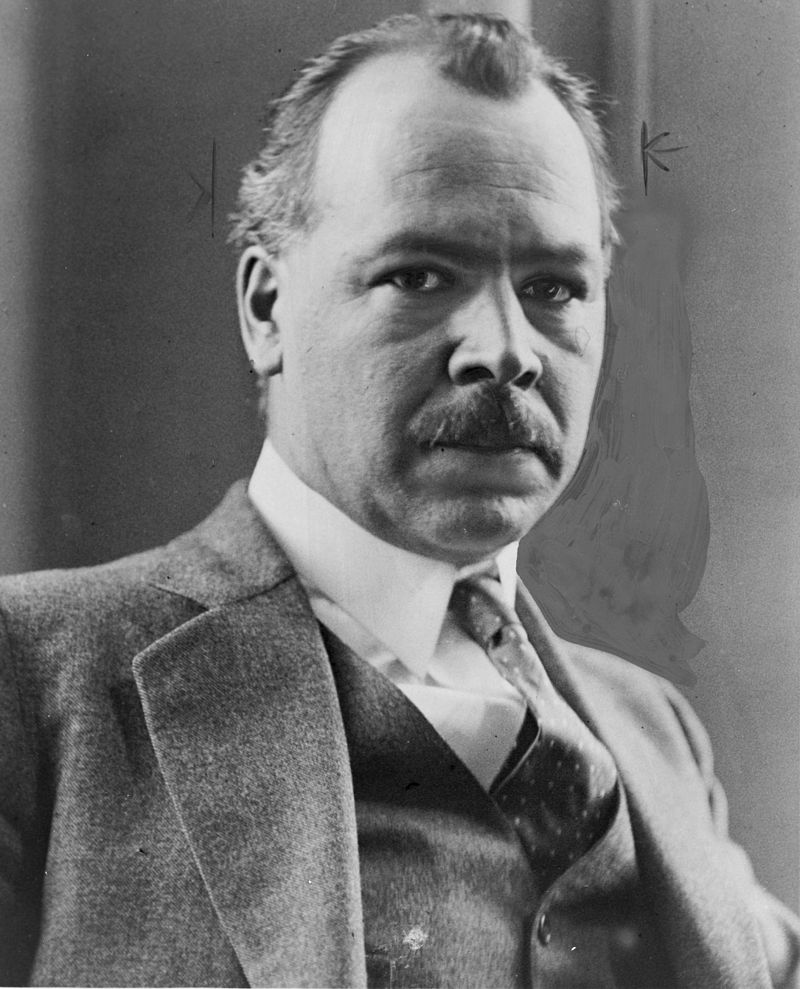

Nikolai Vavilov, a Russian botanist and geneticist, was the inspiration for this year’s symposium. Image credit: Public Domain.

This year’s theme, “The Vavilov Method: Utilizing Genetic Diversity”, celebrated the life and career of Russian botanist Nikolai Vavilov, who identified the centers of origin of cultivated plants. We invited plant scientists and breeders who are applying Vavilov’s ideas through the conservation, collection, and effective utilization of genetic diversity in modern crop breeding programs. This year we also developed a workshop entitled “Where does a breeder go to find genetic diversity?”, which allowed students and faculty to talk about the importance of utilizing genetic diversity in crop improvement and to learn new tools to help them incorporate genetic diversity in breeding programs.

Could you tell us more about how you developed the workshop?

Our aim for the workshop was to engage students and faculty on where we can find genetic diversity, how we can use it, and to include a panel discussion on the challenges and the future of genetic diversity in modern plant breeding programs. As a new value-added event, the workshop was challenging to set up because it required a different set of skills to the rest of the meeting. Once we had an idea of what we wanted, we set up an initial meeting with our speakers where we brainstormed ideas. After several online meetings and e-mails with Professor Paul Gepts (UC Davis), Dr. Colin Khoury (Agricultural Research Service, USDA; check out his recent GPC blog here!), and Professor Susan McCouch (Cornell University), we finalized the structure of the workshop, the layout of the sessions, and the objectives for the speakers. We also had a representative from DivSeek, Dr. Ruth Bastow, on the discussion panel, who contributed to our discussion on future tools for accessing diversity in the future.

How has the symposium grown since the inaugural meeting in 2015?

Every year we want to make the symposium a memorable event, and we want other students and faculty to really get something out of it. We are learning more and more about the students and faculty with these events, particularly in terms of which topics are the most exciting or interesting. The symposium has also grown into a two-day event, with this year’s inclusion of the workshop.

Did you have to overcome any challenges in the organization of the event?

One of our biggest challenges was to secure funding for the event, which is free to attend. To add further value to our event, we wanted to have additional components such as a student research competition and/or workshop, which meant we had to aggressively fundraise from multiple sources. This involved writing a lot of grant proposals both to plant sciences departments across Texas A&M University, as well as to other sources of external funding.

We are grateful to DuPont Pioneer for providing a large amount of the funding. In 2017, we also received sponsorship from the Texas Institute for Genomic Science and Society, Departments of Soil and Crop Sciences, Molecular and Environmental Plant Science, Horticulture, Plant Pathology, and Biology, Texas Grain Sorghum Association, Texas Peanut Producers Board, and Cotton Incorporated. Our beverage sponsor was Pepsi and Kind Snacks was our snack sponsor.

What advice would you give a graduate student trying to organize a similar event?

Plan early and set small goals! Communication is key for a large team to organize such an event. We encourage groups to use Slack or some sort of team work interface. It really helped us to be in constant communication with each other during the months leading up to the symposium.

Could you tell us a little about your own research?

My research (Francisco Gomez) is focused on identifying genomic regions (known as quantitative trait loci; QTLs) associated with mechanical traits that are known to be associated with stem lodging, a major agronomic problem that reduces yields worldwide. My colleague and co-chair, Ammani Kyanam, received her Masters in Plant Breeding in while working in the cotton cytogenetics program in our department. Her research focused on developing genomic tools to facilitate the development of Chromosome Segment Substitution Lines for upland cotton. She is currently mapping QTLs for aphid resistance in sorghum for her Ph.D. You can learn more about the research of our individual committee members at http://plantbreedingsymposium.com/committee/.

How can our readers connect with you?

We have a strong social media presence via Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, where we post event videos, photos and periodical updates. Check them out below!

Facebook: TAMUPBsymposium

Instagram: @pbsymposium

Twitter: @pbsymposium

YouTube: Texas A&M Plant Breeding Symposium

Website: plantbreedingsymposium.com

Email: mailto:pbsymposium@gmail.com

Reproduced with permission

In two short videos, New Phytologist Editor-in-Chief Prof Alistair Hetherington provides a step by step guide for early career researchers, intending to publish their work in New Phytologist.

“One of my top tips would be: get the author list decided very early on.”

Alistair talks through the process of working out whether research is within the scope of the journal, deciding the author list, and submitting a presubmission enquiry.

“Remember, the Editor will use the covering letter to help him or her decide whether or not to send your work out for review. You need to put your work in context, and describe how your findings are novel, and exciting.”

In part two, Alistair explains the submission process, including what should be included in the covering letter. He then describes the peer review process at New Phytologist and what to do after you’ve received a decision on your manuscript.

Read the transcript of both videos on the New Phytologist blog. The audio from the videos is available to download under a Creative Commons licence from the New Phytologist Soundcloud page. You are welcome to redistribute this for teaching purposes.

Reproduced with permission.

New Breeding Technologies in the Plant Sciences – Applications and Implications in Genome Editing

Gothenburg, Sweden, 7-8th July 2017

REGISTRATION FOR THIS MEETING IS NOW OPEN!

Organised by: Dr Ruth Bastow (Global Plant Council), Dr Geraint Parry (GARNet), Professor Stefan Jansson (Umeå University, Sweden) and Professor Barry Pogson (Australian National University, Australia).

Targeted genome engineering has been described as a “game-changing technology” for fields as diverse as human genetics and plant biotechnology. Novel techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, Science’s 2015 Breakthrough of the Year, are revolutionizing scientific research, allowing the targeted and precise editing of genomes in ways that were not previously possible.

Used alongside other tools and strategies, gene-editing technologies have the potential to help combat food and nutritional insecurity and assist in the transition to more sustainable food production systems. The application and use of these technologies is therefore a hot topic for a wide range of stakeholders including scientists, funders, regulators, policy makers and the public. Despite its potential, there are a number of challenges in the adoption and uptake of genome editing, which we propose to highlight during this SEB satellite meeting.

One of the challenges that scientists face in applying technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9 to their research is the technique itself. Although the theoretical framework for using these techniques is easy to follow, the reality is often not so simple. This meeting will therefore explain the principles of applying CRISPR-Cas9 from experts who have successfully used this system in a variety of plant species. We will explore the challenges they encountered as well as some of the solutions and systems they adopted to achieve stably transformed gene-edited plants.

The second challenge for these transformative technologies is how regulatory bodies will treat and asses them. In many countries gene editing technologies do not fit within current policies and guidelines regarding the genetic modification and breeding of plants, as it possible to generate phenotypic variation that is indistinguishable from that generated by traditional breeding methods. Dealing with the ambiguities that techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9 have generated will be critical for the uptake and future use of new breeding technologies. This workshop will therefore outline the current regulatory environment in Europe surrounding gene editing, as well as the approaches being taken in other countries, and will discuss the potential implications and impacts of the use of genome engineering for crop improvement.

Overall this meeting will be of great interest to plant and crop scientists who are invested in the future of gene editing both on a practical and regulatory level. We will provide a forum for debate around the broader policy issues whilst include opportunities for in-depth discussion regarding the techniques required to make this technology work in your own research.

This meeting is being held as a satellite event to the Society for Experimental Biology’s Annual Main Meeting, which takes place in Gothenburg, Sweden, from the 3–6th July 2017.

This week we spoke with Professor Edith Taleisnik about her new book, ‘…¡y nos fuimos por las ramas!’ (‘we went along the branches’), an in-depth look at the history of plant physiology research in Argentina. (Edith previously described the activities and vision of the Argentinean Society of Plant Physiology (SAFV) on the blog – read it here).

Edith, you have put a huge amount of work into uncovering the history of plant physiology research in Argentina. Why did you decide to do it and how did you undertake this challenge?

The current president of the SAFV, Pedro Sansberro, asked Alberto Golberg and myself if we would be willing to document the history of the society. Unaware of the tremendous task ahead, we agreed.

The information was scattered, so the first thing we did was try to collect as many SAFV conference books as possible. Sending requests through the SAFV mailing did not work, so it was essentially through personal contacts that we were able to put together the whole collection of conference books. It is now deposited in the library of CIAP (Centro de Investigaciones Agropecuarias – contact: ciap.cd@inta.gob.ar). People also sent the minutes of past meetings and pictures.

Initially we were only going to analyze the conference books and interview some plant scientists that were among the first disciples of the “founding fathers” of Argentinian experimental plant biology, but as we worked, our book grew and diversified.

What was the most interesting thing you discovered while writing the book?

It’s hard to narrow down which discovery was most exciting!

Victorio Trippi, one of the disciples of the “founding fathers”, told us that many researchers initially published in the journal Phyton, which was founded in Argentina in 1951. Our inspection of the archives of this publication yielded a lot of valuable information, and was an enlightening experience. We traced great names in Argentine plant science to the very beginning of their careers, looking at their topics of interest, how they moved from one job to another, and who their co-authors were. Even earlier than this though, we managed to trace the first mention of plant hormones in Argentina to a paper written by Guillermo Covas in 1939.

Writing the book was rewarding too, because we realized that plant physiology research has steadily grown in Argentina, judging by the participation in the conferences and the amount of research groups all over the country. It was very good to reveal the significant contributions that Argentine experimental plant science has made to many topics, such as photobiology, crop ecophysiology, germination physiology, senescence, mineral nutrition and carbohydrate metabolism, among others.

Image credit: Phil Roeder. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Why did you decide to include essays from the many groups researching plant physiology in Argentina?

We included them to reflect how much plant physiology has grown and diversified in Argentina. In the book we also invite those that did not have a chance to join this edition to contribute to a future one.

What words of wisdom did the researchers who were interviewed want to share with early career researchers for the future?

Most of them emphasized the need for team work, with people from different background joining forces to tackle a specific problem. The SAFV, they point out, has provided a friendly environment that has promoted collaboration and exchange of ideas among its members, and they hope this spirit will persist. They are moderately optimistic about the future, underscoring the need for new research paradigms both in the public and private sectors.

Carlos Ballaré underscored the human aspect of the history of the SAFV in his description of your book, printed on the cover. Could you elaborate on this?

Carlos meant that the book includes personal accounts from the people that have devoted their professional lives to plant physiology and ecophysiology, anecdotes of how the research groups developed and grew, and tales of how researchers replaced the lack of equipment with clever ideas. He highlights that the book has an emphasis on human endeavor, rather than being just a review of numbers, places, and dates.

Beyond the analysis of numbers and growth, the book reveals how early researchers worked on problems that largely sprang from their environment, attempting to understand the causes of issues that had an impact on crop productivity. Thus, those in Tucumán initially worked on sugar cane, those in Mendoza researched grapevines, and the focus in Buenos Aires was potatoes. As groups grew and diversified, this initial link was often blurred; young researchers joining ongoing work never realized what the initial question had been.

In a country where agricultural products or their derivatives still make a significant contribution to GDP, it is sensible to resume the link to local agricultural problems. For this task, it will be essential to adopt a systemic collaborative approach.

To find out more about the book, read our recent news article here.

The book was edited by the SAFV . Printed copies can be purchased by request – please write to Lilian Ayala.

As a reader of our blog, we know that you are passionate about the power of plant science to tackle global challenges, such as food security, climate change, and human health.

The Global Plant Council is dedicated to promoting plant science collaborations across borders to address global challenges in a sustainable way. We are a strong voice for science, but as a not-for-profit organization we need your support.

Help us to keep supporting researchers and plant science by making a single or monthly donation today, via our secure PayPal system.

Click here to visit our donations page, then click the PayPal button to process your payment.

Thank you!