This week on the blog, Professor Sophien Kamoun describes his work on plant–pathogen interactions at The Sainsbury Lab, UK, and discusses the future of plant disease.

Could you begin by describing the focus of your research on plant pathogens?

We study several aspects of plant–pathogen interactions, ranging from genome-level analyses to mechanistic investigations focused on individual proteins. Our projects are driven by some of the major questions in the field: how do plant pathogens evolve? How do they adapt and specialize to their hosts? How do plant pathogen effectors co-opt host processes?

One personal aim is to narrow the gap between research on the mechanisms and evolution of these processes. We hope to demonstrate how mechanistic research benefits from a robust phylogenetic framework to test specific hypotheses about how evolution has shaped molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity and immunity.

Sudden oak death is caused by the oomycete Phytophthora ramorum. Image from Nichols, 2014. PLOS Biology.

Tree diseases such as sudden oak death, ash dieback and olive quick decline syndrome have been making the news a lot recently. Are diseases like these becoming more common, and if so, why?

It’s well documented that the scale and frequency of emerging plant diseases has increased. There are many factors to blame. Increased global trade is one. Climate change is another. There is no question that we need to increase our surveillance and diagnostics efforts. We’re nowhere near having coordinated responses to new disease outbreaks in plant pathology, especially when it comes to deploying the latest genomics methods. We really need to remedy this.

The wheat blast fungus recently hit Bangladesh. Could you briefly outline how it is being tackled by plant pathologists?

Wheat blast has just emerged this last February in Bangladesh – its first report in Asia. It could spread to neighboring countries and become a major threat to wheat production in South Asia. Thus, we had to act fast. We used an Open Science approach to mobilize collaborators in Bangladesh and the wider blast fungus community, and managed to identify the pathogen strain in just a few weeks. It turned out that the Bangladeshi outbreak was caused by a clone related to the South American lineage of the pathogen. Now that we know the enemy, we can proceed to put in place an informed response plan. It’s challenging but at least we know the nature of the pathogen – a first step in any response plan to a disease outbreak.

Which emerging diseases do you foresee having a large impact on food security in the future?

Obviously, any disease outbreak in the major food crops would be of immediate concern, but we shouldn’t neglect the smaller crops, which are so critical to agriculture in the developing world. This is one of the challenges of plant pathology: how to handle the numerous plants and their many pathogens.

European corn boreer. Image from Cornell University. Used under license CC BY 2.0.

As far as new problems, I view insect pests as being a particular challenge. Our basic understanding of insect–plant interactions is not as well developed as it is for microbial pathogens, and research has somewhat neglected the impact of plant immunity. The range of many insect pests is expanding because of climate change, and we are moving to ban many of the widely used insecticides. This is an area of research I would recommend for an early career scientist.

What advice would you give to a young researcher in this area?

Ask the right questions and look beyond the current trends. Think big. Be ambitious. Don’t shy away from embracing the latest technologies and methods. It’s important to work on real world systems. Thanks to technological advances, genomics, genome editing etc., the advantages of working on model systems are not as obvious as they were in the past.

How can we mitigate the risks to crops from plant diseases in the future?

My general take is to be suspicious of silver bullets. I like to say “Don’t bet against the pathogen”. I believe that for truly sustainable solutions, we need to continuously alter the control methods, for example by regularly releasing new resistant crop varieties. Only then we can keep up with rapidly evolving pathogens. One analogy would be the flu jab, which has a different formulation every year depending on the make-up of the flu virus population.

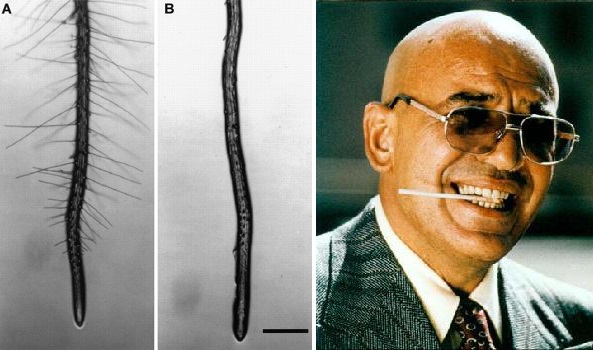

Potato with blight, caused by the oomycete Phytophthora infestans. Image credit: USDA. Used under license CC BY-ND 2.0.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I read that public and private funding of plant science is less than one tenth of biomedical research. Not a great state of affairs when one considers that we will add another two billion people to the planet in the next 30 years. As one of my colleagues once said: “medicine might save you one day; but plants keep you alive everyday”.