One of the world’s most widely used glyphosate-based herbicides, Roundup, can trigger loss of biodiversity, making ecosystems more vulnerable to pollution and climate change, say researchers from McGill University.

The widespread use of Roundup on farms has sparked concerns over potential health and environmental effects globally. Since the 1990s use of the herbicide boomed, as the farming industry adopted “Roundup Ready” genetically modified crop seeds that are resistant to the herbicide. “Farmers spray their corn and soy fields to eliminate weeds and boost production, but this has led to glyphosate leaching into the surrounding environment. In Quebec, for example, traces of glyphosate have been found in Montérégie rivers,” says Andrew Gonzalez, a McGill biology professor and Liber Ero Chair in Conservation Biology.

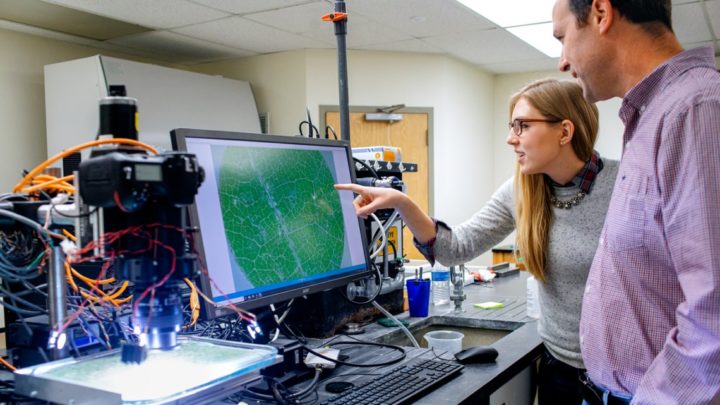

To test how freshwater ecosystems respond to environmental contamination by glyphosate, researchers used experimental ponds to expose phytoplankton communities (algae) to the herbicide. “These tiny species at the bottom of the food chain play an important role in the balance of a lake’s ecosystem and are a key source of food for microscopic animals. Our experiments allow us to observe, in real time, how algae can acquire resistance to glyphosate in freshwater ecosystems,” says post-doctoral researcher Vincent Fugère.

The researchers found that freshwater ecosystems that experience moderate contamination from the herbicide became more resistant when later exposed to a very high level of it – working as a form of “evolutionary vaccination.” According to the researchers, the results are consistent with what scientists call “evolutionary rescue,” which until recently had only been tested in the laboratory. Previous experiments by the Gonzalez group had shown that evolutionary rescue can prevent the extinction of an entire population when exposed to severe environmental contamination by a pesticide thanks to the rapid evolution.

However, the researchers note that the resistance to the herbicide came at a cost of plankton diversity. “We observed significant loss of biodiversity in communities contaminated with glyphosate. This could have a profound impact on the proper functioning of ecosystems and lower the chance that they can adapt to new pollutants or stressors. This is particularly concerning as many ecosystems are grappling with the increasing threat of pollution and climate change,” says Gonzalez.

The researchers point out that it is still unclear how rapid evolution contributes to herbicide resistance in these aquatic ecosystems. Scientist already know that some plants have acquired genetic resistance to glyphosate in crop fields that are sprayed heavily with the herbicide. Finding out more will require genetic analyses that are currently under way by the team.

Read the paper: Nature Ecology & Evolution

Article source: McGill University

Image credit: Vincent Fugère

Strigolactones (SLs) are a class of chemical compounds found in plants that have received attention due to their roles as plant hormones and rhizosphere signaling molecules. They play an important role in regulating plant architecture, as well as promoting germination of root parasitic weeds that have great detrimental effects on plant growth and production.

This study was conducted as part of the SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development) program by Dr. Wakabayashi, Prof. Sugimoto and their colleagues at the Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Kobe University, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Tokyo and Tokushima University. They discovered the orobanchol synthase responsible for converting the SL carlactonoic acid, which promotes symbiotic relationships with fungi, into the SL orobanchol, which causes root parasitic weeds to germinate.

By knocking out the orobanchol synthase gene using genome editing, they succeeded in artificially regulating SL production. This discovery will lead to greater understanding of the functions of each SL and enable the practical application of SLs in the improvement of plant production.

The results of this study were published in the International Scientific Journal Science Advances.

Strigolactones (SL) are a class of chemical compounds that were initially characterized as germination stimulants for root parasitic weeds. SLs have also received attention for their other functions. They play an important role in controlling tiller bud outgrowth and also in promoting mycorrhizal symbiosis in many land plants, whereby plants and fungi mutually exchange nutrients.

Up until now, around 20 SLs have been isolated; with differences in stereochemistry in the C ring and modifications in the A and/or B rings. In recent years, SLs with unclosed BC rings have been discovered. Currently, SLs with a closed ABC ring are designated as canonical SLs, whereas SLs with an unclosed BC ring are non-canonical SLs. However, it is not clear which compounds function as hormones and which compounds function as rhizosphere signals.

If SL production could be suppressed, plants would induce the germination of fewer root parasitic weeds and their adverse effects on crop production would be mitigated. By increasing SL production, on the other hand, plant nutrition would be improved through the promotion of relationships with mycorrhizal fungi. Furthermore, manipulation of the endogenous levels of SL would control plant architecture above ground. Understanding the functions of individual SLs would lead to the development of technology to artificially control plant architecture and the rhizosphere environment. Consequently, there is much interest in how these SLs are biosynthesized.

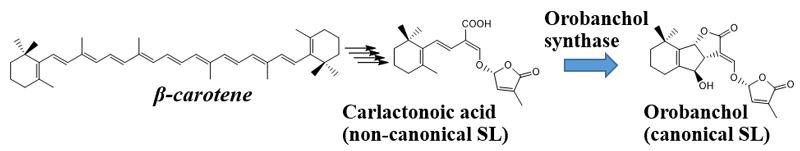

It has been elucidated that SLs are biosynthesized from β-carotene. Four enzymes are involved in conversion of β-carotene to carlactonoic acid (CLA), a common intermediate of SL biosynthesis. In Japonica rice, conversion of CLA into orobanchol proceeds with two enzymes catalyzing two distinct steps. However, the biosynthesis pathway for orobanchol in other plants remained unknown. This study discovered the novel orobanchol synthase, which converts CLA into orobanchol in cowpea and tomato plants (Figure 1).

This research group had isolated orobanchol from cowpea root exudates and determined the structure. From metabolic experiments using cowpea, it was predicted that cytochrome P450 would be involved in the conversion of CLA into orobanchol. In this study, cowpea plants were grown in phosphate rich and poor conditions, where orobanchol production was restricted and promoted, respectively. The genes expressed in the roots of plants in both conditions were comprehensively compared. The group screened for CYP genes whose expression correlated with orobanchol production, expressed them as recombinant proteins, and performed an enzyme reaction assay.

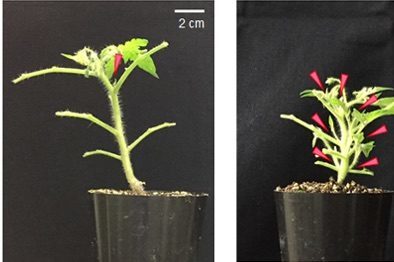

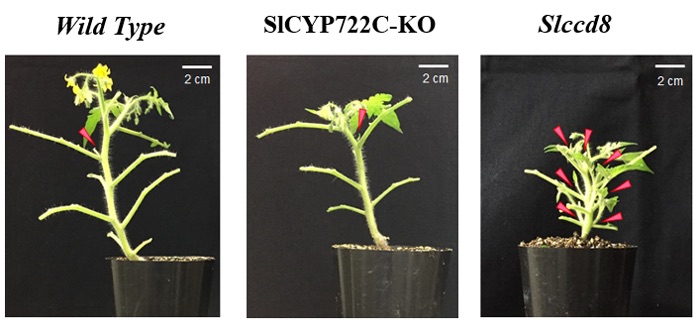

From these results, it was understood that the VuCYP722C enzyme catalyzed the conversion of CLA to orobanchol. Furthermore, the SlCYP722C gene, a homolog of VuCYP722C in tomato was confirmed to be an orobanchol synthase gene. The SlCYP722C gene was knocked out (KO) in tomato plants using genome editing. In contrast to the wild type (control) tomato plants, orobanchol was not detected in root exudates of the KO plants, with CLA being detected instead.

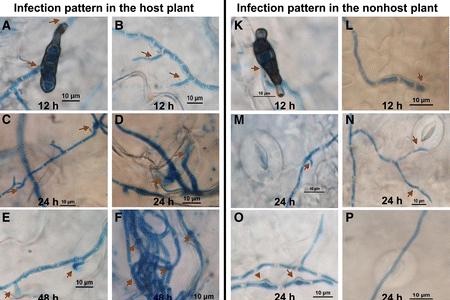

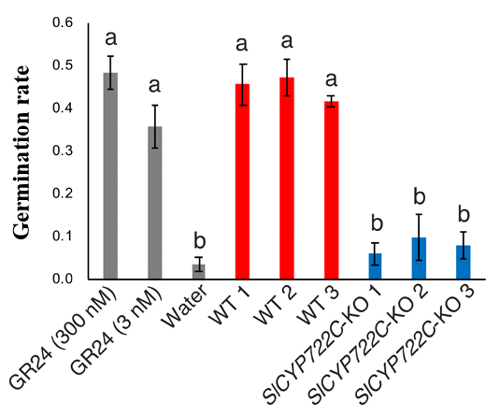

Thus, the research group proved that SlCYP722C is the orobanchol synthase in tomato that converts the non-canonical SL CLA into the canonical SL orobanchol. The architecture of the KO and wild-type plants was comparable (Photo 1). This demonstrated that orobanchol doesn’t control plant architecture in tomato plants. It is thought that these KO tomato plants would still be able to benefit from mycorrhizal fungi, as the activity of CLA against the hyphal branching of the fungi was comparable with that of canonical SLs. Furthermore, it was found that the germination rate of the root parasitic weed Phelipanche aegyptiaca was significantly lower in the hydroponic media of the KO tomato plants (Figure 2). P. aegyptiaca causes great damage to tomato production all over the world, especially around the Mediterranean region. This research showed that it is possible to limit the damage that this parasitic weed does to tomato production by knocking out the orobanchol synthase gene.

This research group succeeded in preventing the synthesis of the major canonical SL orobanchol and accumulating the non-canonical SL carlactonoic acid. The same method can be utilized to elucidate the genes responsible for the biosynthesis of other canonical SLs. Further understanding of the functions of various SLs would allow plants to be manipulated in order to maximize their performance under adverse cultural conditions. Root parasitic weeds detrimentally affect not only tomato but a wide range of other crops including species of Solanaceae, Leguminoceae, Cucurbitaceae and Poaceae. These results will lead to the development of research to alleviate the damage inflicted by root parasitic weeds and increase food production worldwide.

Read the paper: Science Advances

Article source: Kobe University

Image credit: Kobe University

Nearly everyone on Earth is familiar with corn. Literally.

Around the world, each person eats an average of 70 pounds of the grain each year, with even more grown for animal feed and biofuel. And as the global population continues to boom, increasing the amount of food grown on the same amount of land becomes increasingly important.

One potential solution is to develop crops that perform better in cold temperatures. Many people aren’t aware that corn is a tropical plant, which makes it extremely sensitive to cold weather. This trait is problematic in temperate climates where the growing season averages only 4 or 5 months – and where more than 60% of its 1.6 trillion pound annual production occurs.

A chilling-tolerant strain could broaden the latitudes in which the crop could be grown, as well as enable current farmers to increase productivity.

A group of researchers led by David Stern, president of the Boyce Thompson Institute, have taken a step closer to this goal by developing a new type of corn that recovers much more quickly after a cold snap. Stern is also an adjunct professor of plant biology in Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

The research is described in a paper published online in Plant Biotechnology Journal.

“In the field, chilling stress happens most often in the spring when cold temperatures combine with strong sunlight, causing plants to bleach,” Stern said. “So a more chilling-tolerant corn could help farmers plant earlier in the year with confidence that their crop would survive a cold spell and bounce back quickly once the weather warmed up again.”

This work built on research published in 2018, which showed that increasing levels of an enzyme called Rubisco led to bigger and faster-maturing plants. Rubisco is essential for plants to turn atmospheric carbon dioxide into sugar, and its levels in corn leaves decrease dramatically in cold weather.

In the latest study, Stern and colleagues grew corn plants for three weeks at 25°C (77°F), lowered the temperature to 14°C (57°F) for two weeks, and then increased it back up to 25°C.

“The corn with more Rubisco performed better than regular corn before, during and after chilling,” said Coralie Salesse-Smith, the paper’s first author. “In essence, we were able to reduce the severity of chilling stress and allow for a more rapid recovery.” Salesse-Smith was a Cornell PhD candidate in Stern’s lab during the study, and she is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Illinois.

Indeed, compared to regular corn, the engineered corn had higher photosynthesis rates throughout the experiment, and recovered more quickly from the chilling stress with less damage to the molecules that perform the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis.

The end result was a plant that grew taller and developed mature ears of corn more quickly following a cold spell.

Steve Reiners, a co-team leader for Cornell Cooperative Extension’s vegetable program, says that sweet corn is a major vegetable crop in New York, worth about $40-$60 million annually. He notes that many New York corn growers plant as soon as they can because an early crop commands the highest prices of the season.

“Many corn growers in New York plant early under protective plastic sheets to increase soil temperatures, which is expensive. Chilling-tolerant corn could allow farmers to remove that plastic sooner,” Reiners said. “This would expose the plants to additional sunlight, potentially enabling them to mature earlier in the season and get farmers those higher prices.”

Reiners, who was not involved in the study, is also a professor of horticulture at Cornell.

“The corn we developed isn’t yet completely optimized for chilling tolerance, so we are planning the next generation of modifications,” said Stern. “For example, it would be very interesting to add a chilling-tolerant version of a protein called PPDK into the corn and see if it performs even better.”

The researchers believe their approach could also be used in other crops that use the C4 photosynthetic pathway to fix carbon, such as sugar cane and sorghum.

Co-authors on the paper include researchers from The Australian National University in Canberra.

Read the paper: Plant Biotechnology Journal

Article source: Boyce Thompson Institute

Author: Aaron J. Bouchie

Image credit: Jason Koski/Brand Communications