This blog has been reposted with permission from the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory.

Unlike animals, plants can’t run away when things get bad. That can be the weather changing or a caterpillar starting to slowly munch on a leaf. Instead, they change themselves inside, using a complex system of hormones, to adapt to challenges.

Now, MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory scientists are connecting two plant defense systems to how these plants do photosynthesis. The study, conducted in the labs of Christoph Benning and Gregg Howe, is in the journal, The Plant Cell.

At the heart of this connection is the chloroplast, the engine of photosynthesis. It specializes in producing compounds that plants survive with. But plants have evolved ways to use it for other, completely unrelated purposes.

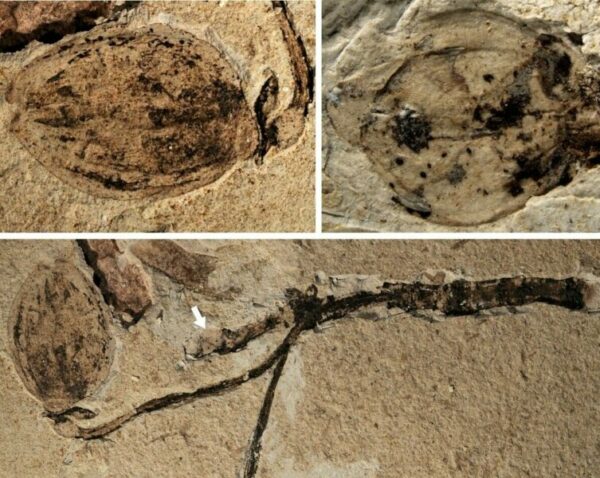

Their trick is to harvest their own chloroplasts’ protective membranes, made of lipids, the molecules found in fats and oils. Lipids have many uses, from making up cell boundaries, to being part of plant hormones, to storing energy.

If plants need lipids for some purpose other than serving as membranes, special proteins break down chloroplast membrane lipids. Then, the resulting products go to where they need to be for further processing.

For example, one such protein, breaks down lipids that end up in plant seed oil. Plant seed oil is both a basic food component and a precursor for biodiesel production.

Now, Kun (Kenny) Wang, a former Benning lab grad student, reports two more such chloroplast proteins with different purposes. Their lipid breakdown products help plants turn on their defense system against living pests and other herbivores. In turn, the proteins, PLIP2 and PLIP3, are themselves activated by another defense system against non-living threats.

In a nutshell, the plant plays a version of the popular children’s game, Telephone, with itself. In the real game, players form a line. The first person whispers a message into the ear of the next person in the line, and so on, until the last player announces the message to the entire group.

In plants, defense systems and chloroplasts also pass along chemical messages down a line. Breaking it down:

“The cross-talk between defense systems has a purpose. For example, there is mounting evidence that plants facing drought are more vulnerable to caterpillar attacks,” Kenny says. “One can imagine plants evolving precautionary strategies for varied conditions. And the cross-talk helps plants form a comprehensive defense strategy.”

Kenny adds, “The chloroplast is amazing. We suspect its membrane lipids spur functions other than defense or oil production. That implies more Telephone games leading to different ends we don’t know yet. We have yet to properly examine that area.”

“Those functions could help us better understand plants and engineer them to be more resistant to complex stresses.”

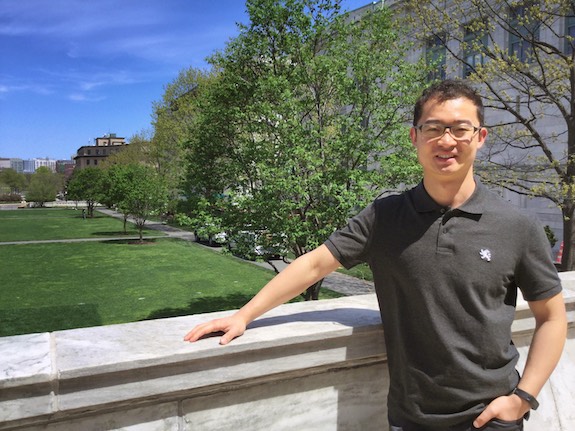

Kenny recently got his PhD from the MSU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. He has just started a post-doc position in the Farese-Walther lab at Harvard Medical School.

“They look at lipid metabolism in mammals and have started a project connecting it with brain disease in humans,” Kenny says. “There is increasing evidence that problems with lipid metabolism in the brain might lead to dementia, Alzheimer’s, etc.”

“I benefited a lot from my time at MSU. The community is very successful here: the people are nice, and you have support from colleagues and facilities. Although we scientists should sometimes be independent in our work, we also need to interact with our communities. No matter how good you are, there is a limit to your impact as an individual. That is one of the lessons I applied when looking for my post-doc.”

Photo of the author, Kun (Kenny) Wang. By Kenny Wang

Read the original article here.

By Atsuko Kanazawa, Igor Houwat, Cynthia Donovan

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

Atsuko Kanazawa is a plant scientist in the lab of David Kramer. Her main focus is on understanding the basics of photosynthesis, the process by which plants capture solar energy to generate our planet’s food supply.

This type of research has implications beyond academia, however, and the Kramer lab is using their knowledge, in addition to new technologies developed in their labs, to help farmers improve land management practices.

One component of the lab’s outreach efforts is its participation in the Legume Innovation Lab (LIL) at Michigan State University, a program which contributes to food security and economic growth in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

Atsuko recently joined a contingent that attended a LIL conference in Burkina Faso to discuss legume management with scientists from West Africa, Central America, Haiti, and the US. The experience was an eye opener, to say the least.

To understand some of the challenges faced by farmers in Africa, take a look at this picture, Atsuko says.

“When we look at corn fields in the Midwest, the corn stalks grow uniformly and are usually about the same height,” Atsuko says. “As you can see in this photo from Burkina Faso, their growth is not even.”

“Soil scientists tell us that much farmland in Africa suffers from poor nutrient content. In fact, farmers sometimes rely on finding a spot of good growth where animals have happened to fertilize the soil.”

Even if local farmers understand their problems, they often find that the appropriate solutions are beyond their reach. For example, items like fertilizer and pesticides are very expensive to buy.

That is where USAID’s Feed the Future and LIL step in, bringing economists, educators, nutritionists, and scientists to work with local universities, institutions, and private organizations towards designing best practices that improve farming and nutrition.

Atsuko says, “LIL works with local populations to select the most suitable crops for local conditions, improve soil quality, and manage pests and diseases in financially and environmentally sustainable ways.”

At the Burkina Faso conference, the Kramer lab reported how a team of US and Zambian researchers are mapping bean genes and identifying varieties that can sustainably grow in hot and drought conditions.

The team is relying on a new technology platform, called PhotosynQ, which has been designed and developed in the Kramer labs in Michigan.

PhotosynQ includes a hand-held instrument that can measure plant, soil, water, and environmental parameters. The device is relatively inexpensive and easy to use, which solves accessibility issues for communities with weak purchasing power.

The heart of PhotosynQ, however, is its open-source online platform, where users upload collected data so that it can be collaboratively analyzed among a community of 2400+ researchers, educators, and farmers from over 18 countries. The idea is to solve local problems through global collaboration.

Atsuko notes that the Zambia project’s focus on beans is part of the larger context under which USAID and LIL are functioning.

“From what I was told by other scientists, protein availability in diets tends to be a problem in developing countries, and that particularly affects children’s development,” Atsuko says. “Beans are cheaper than meat, and they are a good source of protein. Introducing high quality beans aims to improve nutrition quality.”

But, as LIL has found, good science and relationships don’t necessarily translate into new crops being embraced by local communities.

Farmers might be reluctant to try a new variety, because they don’t know how well it will perform or if it will cook well or taste good. They also worry that if a new crop is popular, they won’t have ready access to seed quantities that meet demand.

Sometimes, as Atsuko learned at the conference, the issue goes beyond farming or nutrition considerations. In one instance, local West African communities were reluctant to try out a bean variety suggested by LIL and its partners.

The issue was its color.

“One scientist reported that during a recent famine, West African countries imported cowpeas from their neighbors, and those beans had a similar color to the variety LIL was suggesting. So the reluctance was related to a memory from a bad time.”

This particular story does have a happy ending. LIL and the Burkina Faso governmental research agency, INERA, eventually suggested two varieties of cowpeas that were embraced by farmers. Their given names best translate as, “Hope,” and “Money,” perhaps as anticipation of the good life to come.

Another fruitful, perhaps more direct, approach of working with local communities has been supporting women-run cowpea seed and grain farms. These ventures are partnerships between LIL, the national research institute, private institutions, and Burkina Faso’s state and local governments.

Atsuko and other conference attendees visited two of these farms in person. The Women’s Association Yiye in Lago is a particularly impressive success story. Operating since 2009, it now includes 360 associated producing and processing groups, involving 5642 women and 40 men.

“They have been very active,” Atsuko remarks. “You name it: soil management, bean quality management, pest and disease control, and overall economic management, all these have been implemented by this consortium in a methodical fashion.”

“One of the local farm managers told our visiting group that their crop is wonderful, with high yield and good nutrition quality. Children are growing well, and their families can send them to good schools.”

As the numbers indicate, women are the main force behind the success. The reason is that, usually, men don’t do the fieldwork on cowpeas. “But that local farm manager said that now the farm is very successful, men were going to have to work harder and pitch in!”

Back in Michigan, Atsuko is back to the lab bench to continue her photosynthesis research. She still thinks about her Burkina Faso trip, especially how her participation in LIL’s collaborative framework facilitates the work she and her colleagues pursue in West Africa and other parts of the continent.

“We are very lucky to have technologies and knowledge that can be adapted by working with local populations. We ask them to tell us what they need, because they know what the real problems are, and then we jointly try to come up with tailored solutions.”

“It is a successful model, and I feel we are very privileged to be a part of our collaborators’ lives.”

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

Reposted with kind permission from the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory. Original article.

The need for speed: increasing plant yield is one way to increase food and fuel resources. But asking plants to simply do more of the usual is a strategy that can backfire. Photo by Romain Peli on Unsplash

When engineers want to speed something up, they look for the “pinch points”, the slowest steps in a system, and make them faster.

Say, you want more water to flow through your plumbing. You’d find the narrowest pipe and replace it with a bigger one.

Many labs are attempting this method with photosynthesis, the process that plants and algae use to capture solar energy.

All of our food and most of our fuels have come from photosynthesis. As our population increases, we need more food and fuel, requiring that we improve the efficiency of photosynthesis.

But, Dr. Atsuko Kanazawa and the Kramer Lab are finding that, for biological systems, the “pinch point” method can potentially do more harm than good, because the pinch points are there for a reason! So, how can this be done?

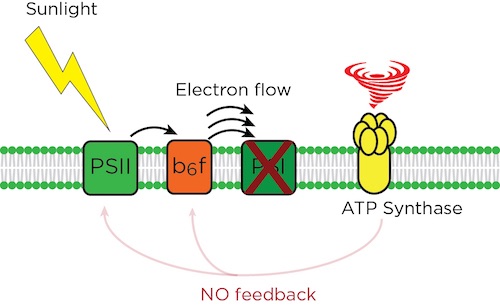

Atsuko and her colleagues at the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory (PRL) have been working on this problem for over 15 years. They have focused on a tiny machine in the chloroplast called the ATP synthase, a complex of proteins essential to storing solar energy in “high energy molecules” that power life on Earth.

That same ATP molecule and a very similar ATP synthase are both used by animals, including humans, to grow, maintain health, and move.

In plants, the ATP synthase happens to be one of the slowest process in photosynthesis, often limiting the amount of energy plants can store.

Photosynthetic systems trap sunlight energy that starts the reaction to move electrons forward in an assembly-line fashion to make useful energy compounds. The ATP synthase is one of the “pinch points” that slows the flow as needed, so plants stay healthy. In cfq, the absence of feedback leads to an electron pile up at PSI, and a crashed system. By MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory, except tornado graphic/CC0 Creative Commons

Atsuko thought, if the ATP synthase is such an important pinch point, what happens if it were faster? Would it be better at photosynthesis and give us faster growing plants?

Years ago, she got her hands on a mutant plant, called cfq, from a colleague. “It had an ATP synthase that worked non-stop, without slowing down, which was a curious example to investigate. In fact, under controlled laboratory conditions – very mild and steady light, temperature, and water conditions – this mutant plant grew bigger than its wild cousin.”

But when the researchers grew the plant under the more varied conditions it experiences in real life, it suffered serious damage, nearly dying.

“In nature, light and temperature quality change all the time, whether through the passing hours, or the presence of cloud cover or winds that blow through the leaves,” she says.

Atsuko’s research now shows that the slowness of the ATP synthase is not an accident; it’s an important braking mechanism that prevents photosynthesis from producing harmful chemicals, called reactive oxygen species, which can damage or kill the plant.

“It turns out that sunlight can be damaging to plants,” says Dave Kramer, Hannah Distinguished Professor and lead investigator in the Kramer lab.

“When plants cannot use the light energy they are capturing, photosynthesis backs up and toxic chemicals accumulate, potentially destroying parts of the photosynthetic system. It is especially dangerous when light and other conditions, like temperature, change rapidly.”

“We need to figure out how the plant presses on the brakes and tune it so that it responds faster…”

The ATP synthase senses these changes and slows down light capture to prevent damage. In that light, the cfqmutant’s fast ATP is a bad idea for the plant’s well-being.

“It’s as if I promised to make your car run faster by removing the brakes. In fact, it would work, but only for a short while. Then things go very wrong!” Dave says.

“In order to improve photosynthesis, what we need is not to remove the brakes completely, like in cfq, but to control them better,” Dave says. “Specifically, we need to figure out how the plant presses on the brakes and tune it so that it responds faster and more efficiently,” David says.

Atsuko adds: “Scientists are trying different methods to improve photosynthesis. Ultimately, we all want to tackle some long-term problems. Crucially, we need to continue feeding the Earth’s population, which is exploding in size.”

The study is published in the journal, Frontiers in Plant Science.

Dr. Sarah Schmidt (@BananarootsBlog), Researcher and Science Communicator at The Sainsbury Laboratory Science. Sarah got hooked on both banana research and science writing when she joined a banana Fusarium wilt field trip in Indonesia as a Fusarium expert. She began blogging at https://bananaroots.wordpress.com and just filmed her first science video. She speaks at public events like the Pint of Science and Norwich Science Festival.

Dr. Sarah Schmidt (@BananarootsBlog), Researcher and Science Communicator at The Sainsbury Laboratory Science. Sarah got hooked on both banana research and science writing when she joined a banana Fusarium wilt field trip in Indonesia as a Fusarium expert. She began blogging at https://bananaroots.wordpress.com and just filmed her first science video. She speaks at public events like the Pint of Science and Norwich Science Festival.

Every morning I slice a banana onto my breakfast cereal.

And I am not alone.

Every person in the UK eats, on average, 100 bananas per year.

Bananas are rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals like potassium and magnesium. Their high carbohydrate and potassium content makes them a favorite snack for professional sports players; the sugar provides energy and the potassium protects the players from muscle fatigue. Every year, around 5000 kg of bananas are consumed by tennis players at Wimbledon.

But bananas are not only delicious snacks and handy energy kicks. For around 100 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa, bananas are staple crops vital for food security. Staple crops are those foods that constitute the dominant portion of a standard diet and supply the major daily calorie intake. In the UK, the staple crop is wheat. We eat wheat-based products for breakfast (toast, cereals), lunch (sandwich), and dinner (pasta, pizza, beer).

In Uganda, bananas are staple crops. Every Ugandan eats 240 kg bananas per year. That is around 7–8 bananas per day. Ugandans do not only eat the sweet dessert banana that we know; in the East African countries such as Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda, the East African Highland banana, called Matooke, is the preferred banana for cooking. Highland bananas are large and starchy, and are harvested green. They can be cooked, fried, boiled, or even brewed into beer, so have very similar uses wheat in the UK.

In West Africa and many Middle and South American countries, another cooking banana, the plantain, is cooked and fried as a staple crop.

In terms of production, the sweet dessert banana we buy in supermarkets is still the most popular. This banana variety is called Cavendish and makes up 47% of the world’s banana production, followed by Highland bananas (24%) and plantains (17%). Last year, I visited Uganda and I managed to combine the top three banana cultivars in one dish: cooked and mashed Matooke, a fried plantain and a local sweet dessert banana!

Another important banana cultivar is the sweet dessert banana cultivar Gros Michel, which constitutes 12% of the global production. Gros Michel used to be the most popular banana cultivar worldwide until an epidemic of Fusarium wilt disease devastated the banana export plantations in the so-called “banana republics” in Middle America (Panama, Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica) in the 1950s.

Fusarium wilt disease is caused by the soil-borne fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (FOC). The fungus infects the roots of the banana plants and grows up through the water-conducting, vascular system of the plant. Eventually, this blocks the water transport of the plant and the banana plants start wilting before they can set fruits.

The Fusarium wilt epidemic in Middle America marked the rise of the Cavendish, the only cultivar that could be grown on soils infested with FOC. The fact that they are also the highest yielding banana cultivar quickly made Cavendish the most popular banana variety, both for export and for local consumption.

Currently, Fusarium wilt is once again the biggest threat to worldwide banana production. In the 1990s, a new race of Fusarium wilt – called Tropical Race 4 (TR4) – occurred in Cavendish plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia. Since then, TR4 has spread to the neighboring countries (Taiwan, the Philippines, China, and Australia), but also to distant locations such as Pakistan, Oman, Jordan, and Mozambique.

In Mozambique, the losses incurred by TR4 amounted to USD 7.5 million within just two years. Other countries suffer even more; TR4 causes annual economic losses of around USD 14 million in Malaysia, USD 121 million in Indonesia, and in Taiwan the annual losses amount to a whopping USD 253 million.

TR4 is not only diminishing harvests. It also raises the price of production, because producers have to implement expensive preventative measures and treatments of affected plantations. These preventive measures and treatments are part of the discussion at The World Banana Forum (WBF). The WBF is a permanent platform for all stakeholders of the banana supply chain, and is housed by the United Nation’s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). In December 2013, the WBF created a special taskforce to deal with the threat posed by TR4.

Despite its massive impact on banana production, we know very little about the pathogen that is causing Fusarium wilt disease. We don’t know how it spreads, why the new TR4 is so aggressive, or how we can stop it.

Breeding bananas is incredibly tedious, because edible cultivars are sterile and do not produce seeds. I am therefore exploring other ways to engineer resistance in banana against Fusarium wilt. As a scientist in the 2Blades group at The Sainsbury Laboratory, I am investigating how we can transfer resistance genes from other crop species into banana and, more recently, I have been investigating bacteria that are able to inhibit the growth and sporulation of F. oxysporum. These biologicals would be a fast and cost-effective way of preventing or even curing Fusarium wilt disease.

Twitter: @BananarootsBlog

Email: mailto:sarah.schmidt@tsl.ac.uk

Website: https://bananaroots.wordpress.com