Although nitrogen is essential for all living organisms — it makes up 3% of the human body — and comprises 78% of Earth’s atmosphere, it’s almost ironically difficult for plants and natural systems to access it.

Atmospheric nitrogen is not directly usable by most living things. In nature, specialized microbes in soils and bodies of water convert nitrogen into ammonia — a crucial form of nitrogen that life can easily access — through a process called nitrogen fixation. In agriculture, soybeans and other legumes that facilitate nitrogen fixation can be planted to restore soil fertility.

An additional obstacle in the process of making nitrogen available to the plants and ecosystems that rely on it is that microbial nitrogen “fixers” incorporate a complex protein called nitrogenase that contains a metal-rich core. Existing research has focused on nitrogenases containing a specific metal, molybdenum.

The extremely small amount of molybdenum found in soil, however, has raised concerns about the natural limits of nitrogen fixation on land. Scientists have wondered what restrictions the scarcity of molybdenum places on nature’s capacity to restore ecosystem fertility in the wake of human-made disturbances, or as people increasingly search for arable land to feed a growing population.

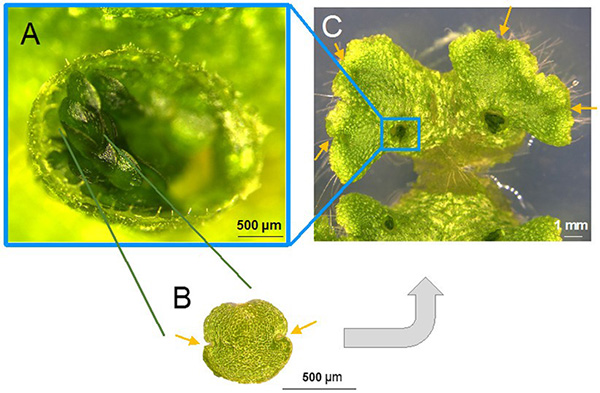

Princeton University researchers have found evidence that nitrogen fixation can be facilitated by metals that are more abundant in soil, which suggests that nitrogen fixation may be more resilient to molybdenum scarcity than previously thought, according to a study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. Working in a 372 mile (600 kilometer) stretch of boreal forest in Canada, the researchers found that nitrogen fixation at an ecosystem scale can also be catalyzed by the metal vanadium, particularly in northern regions with limited natural nitrogen inputs.

“This work prompts a major revision of our understanding of how micronutrients control ecosystem nitrogen status and fertility,” said senior author Xinning Zhang, assistant professor of geosciences and the Princeton Environmental Institute.

“We need to know more about how nitrogen fixation manifests in terms of nutrient budgets, cycling and biodiversity,” she said. “One consequence of this finding is that current estimates of the amount of nitrogen input into boreal forests through fixation may be significantly underestimated. This is a major issue for our understanding of nutrient requirements for forest ecosystems, which currently function as an important sink for anthropogenic carbon.”

First author Romain Darnajoux, a postdoctoral research associate in Zhang’s research group, explained that the findings validate a long-held hypothesis in the scientific community that different metal variants of nitrogenase exist so that organisms can cope with changes in metal availability. The researchers found that vanadium-based nitrogen fixation was only substantive when environmental molybdenum levels were low.

“It would seem that nature evolved backup methods to sustain ecosystem fertility when the environment is variable,” Darnajoux said. “Every nitrogen-cycle step involves an enzyme that requires particular trace metals to work. Molybdenum and iron are typically the focus of scientific study because they’re considered to be essential in the nitrogen-fixing enzyme nitrogenase. However, a vanadium-based nitrogenase also exists, but nitrogen input by this enzyme has been unfortunately largely ignored.”

Darnajoux and Zhang worked with Nicolas Magain and François Lutzoni at Duke University and Marie Renaudin and Jean-Philippe Bellenger at the University of Sherbrooke in Québec.

The researchers’ results suggest that the current estimates of nitrogen input into boreal forests through fixation are woefully low, which would underestimate the nitrogen demand for robust plant growth, Darnajoux said. Boreal forests help mitigate climate change by acting as a sink for anthropogenic carbon. Though these northern forests do not see as many human visitors as even the most lightly populated metropolis, human activities can still have major impacts on forest fertility through the atmospheric transport of air pollution loaded with nitrogen and metals such as molybdenum and vanadium.

“Human activities that substantially change air quality can have a far-reaching influence on how even remote ecosystems function,” Zhang said. “The findings highlight the importance of air pollution in altering micronutrient and macronutrient dynamics. Because air is a global commons, the connection between metals and nitrogen cycling and air pollution has some interesting policy and management dimensions.”

The researchers’ findings could help in the development of more accurate climate models, which do not explicitly contain information on molybdenum or vanadium in simulations of the global flow of nitrogen through the land, ocean and atmosphere.

The importance of vanadium-driven nitrogen fixation extends to other high-latitude regions, and most likely to temperate and tropical systems, Darnajoux and Zhang said. The threshold for the amount of molybdenum an ecosystem needs to activate or deactivate vanadium nitrogen fixation that they found in their study was remarkably similar to the molybdenum requirements of nitrogen fixation found for samples spanning diverse biomes.

The researchers will continue the search for vanadium-based nitrogen fixation in the northern latitudes. They’ve also turned their eyes toward areas closer to home, initiating studies of micro- and macronutrient dynamics in temperate forests in New Jersey, and they plan to expand their work to tropical systems.

Read the paper: Proceedings of the National Academy of Science

Article source: Princeton University

Author: Joseph Albanese

Image credit: Marie Renaudin, University of Sherbrooke