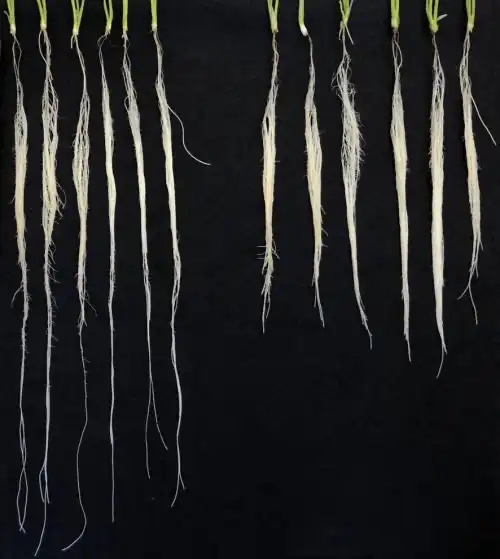

An international team of scientists found that the right number of copies of a specific group of genes can stimulate longer root growth, enabling wheat plants to pull water from deeper supplies. The resulting plants have more biomass and produce…

Read More