This week’s post was written by Jonathan Ingram, Senior Commissioning Editor / Science Writer for the Journal of Experimental Botany. Jonathan moved from lab research into publishing and communications with the launch of Trends in Plant Science in 1995, then going on to New Phytologist and, in the third sector, Age UK and Mind.

In this week of the XIXth International Botanical Congress (IBC) in Shenzhen, it seems appropriate to highlight outstanding research from labs in China. More than a third of the current issue of Journal of Experimental Botany is devoted to papers from labs across this powerhouse of early 21st century plant science.

Collaborations are key, and this was a theme that came up time again at the congress. The work by Yongzhe Gu et al. is a fine example, involving scientists at four institutions studying a WRKY gene in wild and cultivated soybean: in Beijing, the State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany at the Institute of Botany in the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences; and in Harbin (Heilongjiang), the Crop Tillage and Cultivation Institute at Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and the College of Agriculture at Northeast Agricultural University. Interest here centers on the changes which led to the increased seed size in cultivated soybean with possible practical application in cultivation and genetic improvement of such a vital crop.

Botanic gardens are also part of the picture. In another paper in the same issue, Yang Li et al. from the Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden in Kunming (Yunnan) and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing present research on DELLA-interacting proteins in Arabidopsis. Here the authors show that bHLH48 and bHLH60 are transcription factors involved in GA-mediated control of flowering under long-day conditions.

Naturally, research on rice is important. Wei Jiang et al. from the National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan) describe their research on WOX11 and the control of crown root development in the nation’s grain of choice, which will be important for breeders looking to increase crop yields and resilience.

The other work featured is either in Arabidopsis or plants of economic importance: Fangfang Zheng et al. (Qingdao Agricultural University, also with collaborators in Maryland) and Xiuli Han et al. (Beijing); Yun-Song Lai et al. (Beijing/Chengdu – cucumber), Wenkong Yao et al. (Yangling, Shaanxi – Chinese grapevine, Vitis pseudoreticulata), and Xiao-Juan Liu et al. (Tai-an, Shandong – apple).

Shenzehn has grown rapidly and is now highly significant for life science as home to the China National GeneBank (CNGB) project led by BGI Genomics. The vision as set out by Huan-Ming Yang, chairman of BGI-Shenzhen, is profound – from sequencing what’s already here, often in numbers per species, to innovative synthetic biology.

Shenzehn is also home to another significant institution, the beautiful and scientifically important Fairy Lake Botanic Garden. At the IBC, the importance of biodiversity conservation for effective, economically focused plant science, but also for so many other reasons to do with our intimate relationship with plants and continued co-existence on the planet, was a central theme.

The research highlighted in Journal of Experimental Botany is part of the wider, positive growth of plant science (and, indeed, botany) not just in China, but worldwide. The Shenzehn Declaration on Plant Sciences with its seven priorities for strategic action, launched at the congress, will be a guide for the right development in coming years.

Professor Henk Hilhorst (Wageningen University and Research)

This week we spoke to Professor Henk Hilhorst (Wageningen University and Research) about his research on desiccation tolerance in seeds and plants.

Could you begin by telling us a little about your research?

I am a plant physiologist specializing in seed biology. I have a long research record on various aspects of seeds, including the mechanisms and regulation of germination and dormancy, desiccation tolerance, as well as issues in seed technology. Being six years from retirement now, I decided to extend my desiccation tolerance studies from seeds to resurrection plants, which display vegetative desiccation tolerance. I strongly believe that unveiling of the mechanism of vegetative desiccation tolerance may help us create crops that are truly tolerant to severe drought, rather than (temporarily) resistant.

How did you become interested in this field of study, and how has your career progressed?

As with many things in life, it was coincidence. I majored in plant biochemistry and applied for a PhD position in seed biology. After obtaining the degree I was offered a tenure track position in seed physiology by the Laboratory of Plant Physiology at Wageningen University, where I still work as a faculty member. My career has progressed nicely and I am an authority in the field of seed science, editor-in-chief of the journal Seed Science Research, and will become the President of the International Society for Seed Science in September of this year.

I see my current work on vegetative desiccation tolerance as a highlight in my professional life. I have always been more interested in the desiccation tolerance of seeds until about five years ago, when my current collaborator Prof Jill Farrant of the University of Cape Town, South-Africa, made me enthusiastic about these wonderful resurrection plants. We started to work together and published our first study recently in Nature Plants.

Read the paper here ($): A footprint of desiccation tolerance in the genome of Xerophyta viscosa.

In your recent paper, you sequenced the genome of the resurrection plant, Xerophyta viscosa, which can survive with less than a 5% relative water content. How is it possible for a plant to lose so much of its water and still survive?

These plants have a lot of characteristics that we’ve seen in seeds. They display protective desiccation tolerance mechanisms in their leaves, including anti-oxidants, protective proteins, and even dismantle their photosynthetic machinery during periods of drought. Even the cell wall structure and composition of resurrection plants resemble those of seeds. We are currently working on a paper describing the striking similarities between seeds and resurrection plants.

What was the most interesting discovery you made upon sequencing the genome of the resurrection plant?

First, the similarities between resurrection plants and seeds listed above were also apparent at the molecular level. For example, previous work suggested that the “ABI3 regulon”, consisting of about 100 genes regulated by the transcription factor ABI3, is specific to seeds, but we found that it is almost completely present (and active) in the leaves of Xerophyta viscosa too!

Secondly, we found “islands” or clusters of genes specific for desiccation tolerance that aren’t found in other species. Many of these regulate secondary metabolite pathways.

How challenging was it to sequence the genome of this plant? How did you overcome any difficulties?

It was very challenging. First, the species is an octoploid, meaning it has eight copies of each chromosome. This meant that we had to sequence its genome at very high coverage and employing the most advanced sequencing facilities, e.g. PacBio. Getting funding for this complex analysis was another challenge. We then took almost a year to assemble the genome and annotate it at the desired quality.

You identified some of the most important genes involved in desiccation tolerance. Is it possible to translate this work into other species, such as crops that may be threatened by drought as the climate changes?

That will be our ultimate goal. It’s important to remember that desiccation-sensitive plants, including all our major crops, produce seeds that are desiccation tolerant. This implies that the information for desiccation tolerance is present in the genomes of these crops but that it is only turned on in the seeds. We are trying to determine how this is localized, in order to find a method to turn on the desiccation tolerance mechanism in vegetative parts of the (crop) plant too. In parallel we are expressing some of the key transcription factors from Xerophyta viscosa in some important crops to see how this affects them.

Are there any other interesting aspects of Xerophyta viscosa biology?

Contrary to plants that wilt and ultimately die because of (severe) drought, leaves of resurrection species do not show such stress-related senescence. This is related to the engagement of active anti-senescence genes during the drying of the leaves of resurrection species. We are currently investigating these senescence-related mechanisms too.

The rose of Jericho (Anastatica hierochuntica) is another resurrection plant. Image credit: FloraTrek. Used under license: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Do you expect to find that different types of desiccation-tolerant plants use the same subset of genes to survive drought, or could they have developed other pathways to resilience?

We expect that the core mechanism is very similar among the resurrection species but that each species may have adapted to its specific environment.

Funding permitting, we will sequence the genomes of at least another ten resurrection species to further clarify the various evolutionary pathways to desiccation tolerance and, importantly, to discriminate between species-specific and desiccation tolerance-specific genes.

What advice do you have for early career researchers?

Stick to what you believe in, even if you have to (temporarily) be involved in research that you appreciate less, e.g., because of better funding opportunities.

Read Henk’s recent paper in Nature Plants here ($): A footprint of desiccation tolerance in the genome of Xerophyta viscosa.

By Lucina Melesio

Creole — or native — varieties of maize are derived from improvements made over thousands of years by local farmers, and contain genes that help them adapt to different environments.

“We are now using this analysis to find other genes that are of vital importance to breeders, such as those resistant to extreme heat, frost or drought — environmental conditions associated with climate change and that could affect maize production.”

Sarah Hearne, CIMMYT

“Latin American breeders will be able to use these results to identify native varieties that could contribute to improved adaptation”, Edward Buckler, a Cornell University researcher and co-author of the study published in Nature Genetics (February 6), told SciDev.Net.

The information on the genetic markers described in the study will be available online, said Sarah Hearne, a researcher at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and co-author of the study. “Meanwhile, any breeder can contact us to request information”, she said.

“We are now using this analysis to find other genes that are of vital importance to breeders, such as those resistant to extreme heat, frost or drought — environmental conditions associated with climate change and that could affect maize production”, Hearne said.

Maize ears from CIMMYT’s collection, showing a wide variety of colors and shapes. CIMMYTs germplasm bank contains about 28,000 unique samples of cultivated maize and its wild relatives, teosinte and Tripsacum. These include about 26,000 samples of farmer landracestraditional, locally-adapted varieties that are rich in diversity. The bank both conserves this diversity and makes it available as a resource for breeding.

Photo credit: Xochiquetzal Fonseca/CIMMYT.

Studying native maize varieties is extremely difficult because of their genetic variation. Although domesticated, they are wilder than commercial varieties.

For this study, the researchers cultivated hybrid creole varieties in various environments in Latin America and identified regions of the genome that control growth rates. They looked into where the varieties came from and what genetic features contributed to their growth in that environment.

Hearne added that the research team has initiated a “pre-breeding” programme with a small group of breeders in Mexico. As part of that programme, CIMMYT delivers to breeders materials from its germplasm bank of Creole maize; it also provides molecular information the breeders can use to generate new varieties.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Latin America and Carribean edition.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.

This week’s post comes to us from Crystal Chan, project manager of the Application of Genomic Innovation in the Lentil Economy project led by Dr. Kirstin Bett at the Department of Plant Sciences, University of Saskatchewan.

Could you begin with a brief introduction to your research?

Our research focuses on the smart use of diverse genetic materials and wild relatives in the lentil (Lens culinaris) breeding program.

Canada has become the world’s largest producer and exporter of lentils in recent years. Lentils are an introduced species to the northern hemisphere and, until recently, our breeding program at the University of Saskatchewan involved just a handful of germplasms adapted to our climatic condition. With dedicated breeding efforts we have achieved noteworthy genetic gains in the past decade, but we are missing out on the vast genetic diversity available within the Lens genus. This is a major dilemma faced by all plant breeders: do we want consistency (sacrificing genetic diversity and reducing genetic gains over time) or diversity (sacrificing some important fixed traits and spending lots of time and resources in “backcrossing/rescue efforts”)?

In our current research, we use genomic tools to understand the genetic variability found in different lentil genotypes and the basis of what makes lentils grow well in different global environments (North America vs. Mediterranean countries vs. South Asian countries). We will then develop molecular breeding tools that breeders can use to improve the diversity and productivity of Canadian lentils while maintaining their adaptation to the northern temperate climate.

What first led you to this research topic?

Dr. Albert (Bert) Vandenberg, professor and lentil breeder at the University of Saskatchewan, noticed one of the wild lentil species was resistant to several diseases that devastate the cultivated lentil. After years of dedicated breeding effort, he was able to transfer the resistance traits to the cultivated lentil, but it took a lot of time and resources. We began looking into other beneficial traits and became fascinated with the domestication and adaptation aspects of lentil – after all lentil is one of the oldest cultivated crops, domesticated by man around 11,000 BC! With the rapid advance in genomic technology, we can start to better understand the biology and develop tools to harness these valuable genetic resources.

You have been involved in the development of tools that assist researchers to build databases of genomics and genetics data. Could you tell us more about projects such as Tripal?

Over the past six years, Lacey Sanderson (bioinformaticist in our group) has developed a database for our pulse research program at the University (Knowpulse, http://knowpulse.usask.ca/portal/). The database is specifically designed to present data that is relevant to breeders, as our group has a strong focus on variety development for the Canadian pulse crop industry. Knowpulse houses genotypic information from past and on-going lentil genomics projects, and includes tools for looking up genotypes as well as comparing the current genome assembly (currently v1.2) and other sequenced legume genomes. The tools are being developed in Tripal, an open-source toolkit that provides an interface between the data and a Drupal web content management system, in collaboration with colleagues at Washington State University.

At the moment we are developing new functionalities that will allow us to store and present germplasm information as well as phenotypic data. We are also working with our colleagues at Washington State University (under the “Tripal Gateway Project” funded by the National Science Foundation) to enhance interconnectivity between Knowpulse and other legume databases, such as the Legume Information Service (LIS) and Soybase, to facilitate comparative genomic studies.

How challenging are pulse genomes to assemble? How closely related are the various crops?

We had the fortune to lead the lentil genome sequencing initiative thanks to the support from producer groups and governments across the globe. The lentil genome is really challenging to assemble! We see nice synteny between lentil and the model legume, medicago, however the lentil genome is much bigger. We see a significant increase in genome size between chickpea and beans versus lentil (and pea for that matter), yet we have evidence to show that genome duplication is not the cause of the size increase. There are a lot of very long repetitive elements sprinkled around the genome, which makes its sequencing and proper assembly very challenging. Not to mention understanding the role of these long repetitive elements in biological functions…

What insights into crop domestication have you gained from these genomes?

That’s what we are working on right now under the AGILE (“Application of Genomics to Innovation in the Lentil Economy”) project. Stay tuned!

Do you work with breeders to develop new cultivars? What sorts of traits are most important?

Breeding is at the core of our work – both Kirstin and Bert are breeders (Kirstin has an active dry bean breeding program when she’s not busy with genomic research). All our research aims to feed information to the breeders so that they can make better crossing and selection decisions. Our work in herbicide tolerance has led to the development and implementation of a molecular marker to screen for herbicide resistance. With that marker we save time (skipping a crossing cycle) and forego the herbicide spraying test for all of our early materials.

Disease resistance and drought tolerance are also important for the growers. Visual quality (seed shape, size, color) are very important too as our customers are very picky as to what sort of lentils they like to buy/eat.

What does the future of legume/lentil agriculture hold?

Lentils have been a staple food in many countries for centuries and have been gaining popularity in North America in recent years as people are looking for plant-based protein sources. Lentils are high in fibre, protein, and complex carbohydrates, while low in fat and calories, and have a low glycemic index. They are suitable for vegetarian/vegan, gluten-free, diabetic, and heart-smart diets. Lentils also provide essential micronutrients such as iron, zinc and folates. Lentils are widely recognized as nutrient-dense food that could serve as part of the solution to combat global food and nutritional insecurity.

In modern agriculture, adding lentil or other leguminous crops in the crop rotation helps improve soil structure, soil quality, and biotic diversity, as well as enhancing soil fertility through their ability to fix nitrogen. Because pulse crops require little to no nitrogen fertilizer, they use half of the non-renewable energy inputs of other crops, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

2016 was marked by the United Nations as the International Year of Pulses, which was great as many people have become more aware of the benefits of pulse crops on the plate and in the field.

Follow us on twitter (@Wildlentils) for research updates!

All images are credited to Mr Derek Wright.

Sales of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) have exploded in the last decade, with prices more than tripling between 2008 and 2014. The popularity of this pseudocereal comes from its highly nutritious seeds, which resemble grains and contain a good balance of protein, vitamins, and minerals. The nourishing nature of quinoa meant it was prized by the Incas, who called it the “Mother grain”.

Quinoa is a popular ‘grain’, but it is more closely related to spinach and beetroot than cereals like wheat or barley. Image credit: Flickr user. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Quinoa is native to the Andes of South America, where it thrives in a range of conditions from coastal regions to alpine regions of up to 4000 m above sea level. Its resilience and nutritious seeds means that quinoa has been identified as a key crop for enhancing food security, but there are currently very few breeding programs targeting this species.

The challenge of improving the efficiency and sustainability of quinoa production has so far been restricted by the lack of a reference genome. This week, a team of researchers led by Professor Mark Tester (King Abdullah University of Science & Technology; KAUST) addressed this issue, publishing a high-quality genome sequence for quinoa in Nature. They compared the genome with that of related species to characterize the evolution and domestication of the crop, and investigated the genetic diversity of economically important traits.

The evolution of quinoa

Tester and colleagues used an array of genomics techniques to assemble 1.39 Gb of the estimated 1.45-1.50 Gb full length of quinoa’s genome. Quinoa is a tetraploid, meaning it has four copies of each chromosome. The researchers shed light on the evolutionary history of this crop by sequencing descendants of the two diploid species (each containing two sets of chromosomes) that hybridized to generate quinoa; kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule) and Swedish goosefoot (Chenopodium suecicum). Comparing these sequences to quinoa and other relatives, the team showed that the hybridization event likely occurred between 3.3 and 6.3 million years ago. A comparison with other closely related Chenopodium species also suggested that, contrary to previous predictions, quinoa may have been domesticated twice, both in highland and coastal environments.

Quinoa field. Image credit: LID. Used under license: CC BY-SA 2.0.

Washing away quinoa’s bitter taste

Quinoa seeds are coated with soap-like chemicals called saponins, which have a bitter taste that deters herbivores. Saponins can disrupt the cell membranes of red blood cells, so they have to be removed before human consumption, but this process is costly, so quinoa breeders are always looking for varieties that produce lower levels of saponins.

Sweet (low-saponin) quinoa strains do occur naturally, but the genes that regulate this phenotype were previously unknown. Tester and colleagues investigated sweet and bitter quinoa strains and discovered that a single gene (TRITERPENE SAPONIN BIOSYNTHESIS ACTIVATING REGULATOR-LIKE 1 [TSARL1]) controls the amount of saponins produced in the seeds. The low-saponin quinoa strains contained mutations in TSARL1 that prevented it from functioning properly. This is a key target for the improvement of quinoa in the future, although farmers will have to find new ways to protect their crops from birds and other seed predators!

Quinoa flowers. Image credit: Alan Cann. Used under license: CC BY-SA 2.0.

Quality quinoa

The high-quality reference genome for quinoa generated by Tester and colleagues is likely to be vital for allowing many exciting improvements in the future. Breeders hoping to improve the yield, ease of harvest, stress tolerance, and saponin content of quinoa can develop genetic markers to speed up breeding for these key traits, improving the productivity of quinoa varieties and enhancing future food security.

Read the paper in Nature: Jarvis et al., 2017. The genome of Chenopodium quinoa. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/nature21370

Thank you to Professor Mark Tester (KAUST) for providing information used in this post!

Another fantastic year of discovery is over – read on for our 2016 plant science top picks!

A Zostera marina meadow in the Archipelago Sea, southwest Finland. Image credit: Christoffer Boström (Olsen et al., 2016. Nature).

The year began with the publication of the fascinating eelgrass (Zostera marina) genome by an international team of researchers. This marine monocot descended from land-dwelling ancestors, but went through a dramatic adaptation to life in the ocean, in what the lead author Professor Jeanine Olsen described as, “arguably the most extreme adaptation a terrestrial… species can undergo”.

One of the most interesting revelations was that eelgrass cannot make stomatal pores because it has completely lost the genes responsible for regulating their development. It also ditched genes involved in perceiving UV light, which does not penetrate well through its deep water habitat.

Read the paper in Nature: The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea.

BLOG: You can find out more about the secrets of seagrass in our blog post.

Plants are known to form new organs throughout their lifecycle, but it was not previously clear how they organized their cell development to form the right shapes. In February, researchers in Germany used an exciting new type of high-resolution fluorescence microscope to observe every individual cell in a developing lateral root, following the complex arrangement of their cell division over time.

Using this new four-dimensional cell lineage map of lateral root development in combination with computer modelling, the team revealed that, while the contribution of each cell is not pre-determined, the cells self-organize to regulate the overall development of the root in a predictable manner.

Watch the mesmerizing cell division in lateral root development in the video below, which accompanied the paper:

Read the paper in Current Biology: Rules and self-organizing properties of post-embryonic plant organ cell division patterns.

In March, a Spanish team of researchers revealed how the anti-wilting molecular machinery involved in preserving cell turgor assembles in response to drought. They found that a family of small proteins, the CARs, act in clusters to guide proteins to the cell membrane, in what author Dr. Pedro Luis Rodriguez described as “a kind of landing strip, acting as molecular antennas that call out to other proteins as and when necessary to orchestrate the required cellular response”.

Read the paper in PNAS: Calcium-dependent oligomerization of CAR proteins at cell membrane modulates ABA signaling.

*If you’d like to read more about stress resilience in plants, check out the meeting report from the Stress Resilience Forum run by the GPC in coalition with the Society for Experimental Biology.*

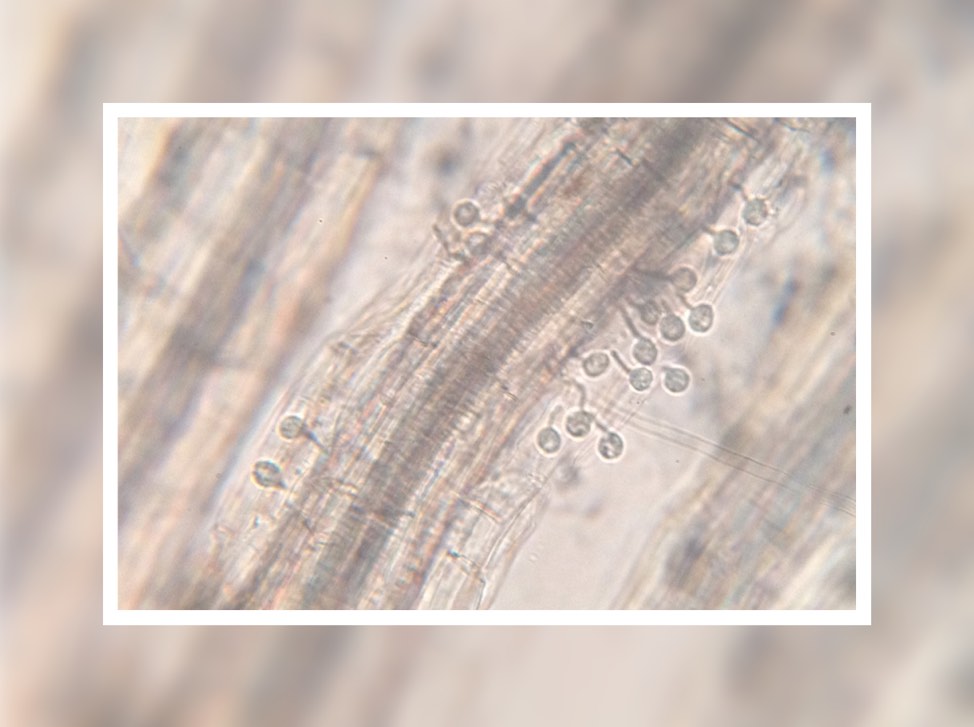

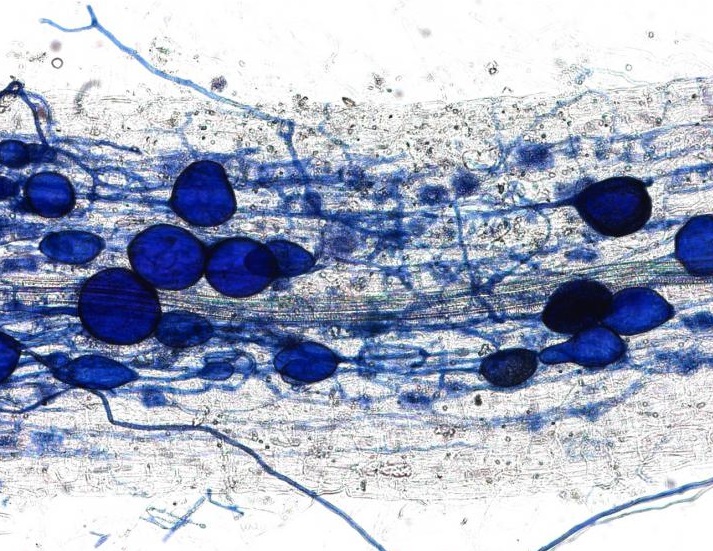

This plant root is infected with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Image credit: University of Zurich.

In April, we received an amazing insight into the ‘decision-making ability’ of plants when a Swiss team discovered that plants can punish mutualist fungi that try to cheat them. In a clever experiment, the researchers provided a plant with two mutualistic partners; a ‘generous’ fungus that provides the plant with a lot of phosphates in return for carbohydrates, and a ‘meaner’ fungus that attempts to reduce the amount of phosphate it ‘pays’. They revealed that the plants can starve the meaner fungus, providing fewer carbohydrates until it pays its phosphate bill.

Author Professor Andres Wiemsken explains: “The plant exploits the competitive situation of the two fungi in a targeted manner, triggering what is essentially a market-based process determined by cost and performance”.

Read the paper in Ecology Letters: Options of partners improve carbon for phosphorus trade in the arbuscular mycorrhizal mutualism.

The transition of ancient plants from water onto land was one of the most important events in our planet’s evolution, but required a massive change in plant biology. Suddenly plants risked drying out, so had to develop new ways to survive drought.

In May, an international team discovered a key gene in moss (Physcomitrella patens) that allows it to tolerate dehydration. This gene, ANR, was an ancient adaptation of an algal gene that allowed the early plants to respond to the drought-signaling hormone ABA. Its evolution is still a mystery, though, as author Dr. Sean Stevenson explains: “What’s interesting is that aquatic algae can’t respond to ABA: the next challenge is to discover how this hormone signaling process arose.”

Read the paper in The Plant Cell: Genetic analysis of Physcomitrella patens identifies ABSCISIC ACID NON-RESPONSIVE, a regulator of ABA responses unique to basal land plants and required for desiccation tolerance.

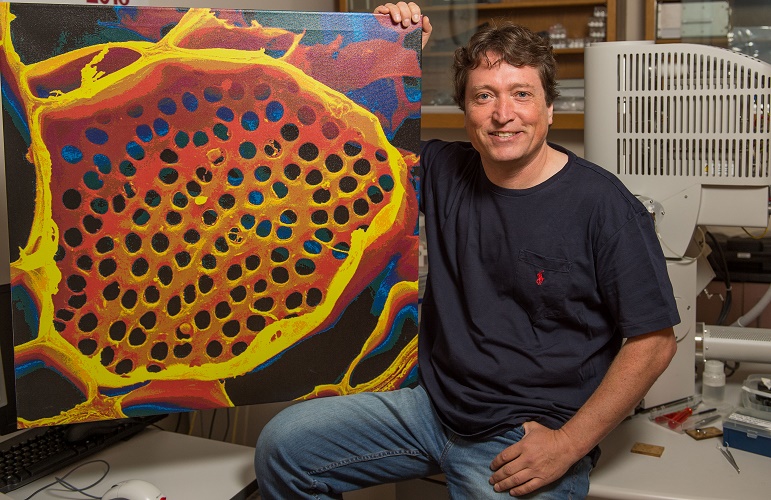

Professor Michael Knoblauch shows off a microscope image of phloem tubes. Image credit: Washington State University.

Sometimes revisiting old ideas can pay off, as a US team revealed in June. In 1930, Ernst Münch hypothesized that transport through the phloem sieve tubes in the plant vascular tissue is driven by pressure gradients, but no-one really knew how this would account for the massive pressure required to move nutrients through something as large as a tree.

Professor Michael Knoblauch and colleagues spent decades devising new methods to investigate pressures and flow within phloem without disrupting the system. He eventually developed a suite of techniques, including a picogauge with the help of his son, Jan, to measure tiny pressure differences in the plants. They found that plants can alter the shape of their phloem vessels to change the pressure within them, allowing them to transport sugars over varying distances, which provided strong support for Münch flow.

Read the paper in eLife: Testing the Münch hypothesis of long distance phloem transport in plants.

BLOG: We featured similar work (including an amazing video of the wound response in sieve tubes) by Knoblauch’s collaborator, Dr. Winfried Peters, on the blog – read it here!

Preserved remains of rope, seeds, reeds and pellets (left), and a desiccated barley grain (right) found at Yoram Cave in the Judean Desert. Credit: Uri Davidovich and Ehud Weiss.

In July, an international and highly multidisciplinary team published the genome of 6,000-year-old barley grains excavated from a cave in Israel, the oldest plant genome reconstructed to date. The grains were visually and genetically very similar to modern barley, showing that this crop was domesticated very early on in our agricultural history. With more analysis ongoing, author Dr. Verena Schünemann predicts that “DNA-analysis of archaeological remains of prehistoric plants will provide us with novel insights into the origin, domestication and spread of crop plants”.

Read the paper in Nature Genetics: Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley.

BLOG: We interviewed Dr. Nils Stein about this fascinating work on the blog – click here to read more!

Another exciting cereal paper was published in August, when an Australian team revealed that C4 photosynthesis occurs in wheat seeds. Like many important crops, wheat leaves perform C3 photosynthesis, which is a less efficient process, so many researchers are attempting to engineer the complex C4 photosynthesis pathway into C3 crops.

This discovery was completely unexpected, as throughout its evolution wheat has been a C3 plant. Author Professor Robert Henry suggested: “One theory is that as [atmospheric] carbon dioxide began to decline, [wheat’s] seeds evolved a C4 pathway to capture more sunlight to convert to energy.”

Read the paper in Scientific Reports: New evidence for grain specific C4 photosynthesis in wheat.

Professor Stefan Jansson cooks up “Tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables”. Image credit: Stefan Jansson.

September marked an historic event. Professor Stefan Jansson cooked up the world’s first CRISPR meal, tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables (genome-edited cabbage). Jansson has paved the way for CRISPR in Europe; while the EU is yet to make a decision about how CRISPR-edited plants will be regulated, Jansson successfully convinced the Swedish Board of Agriculture to rule that plants edited in a manner that could have been achieved by traditional breeding (i.e. the deletion or minor mutation of a gene, but not the insertion of a gene from another species) cannot be treated as a GMO.

Read more in the Umeå University press release: Umeå researcher served a world first (?) CRISPR meal.

BLOG: We interviewed Professor Stefan Jansson about his prominent role in the CRISPR/GM debate earlier in 2016 – check out his post here.

*You may also be interested in the upcoming meeting, ‘New Breeding Technologies in the Plant Sciences’, which will be held at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, on 7-8 July 2017. The workshop has been organized by Professor Jansson, along with the GPC’s Executive Director Ruth Bastow and Professor Barry Pogson (Australian National University/GPC Chair). For more info, click here.*

Phytochromes help plants detect day length by sensing differences in red and far-red light, but a UK-Germany research collaboration revealed that these receptors switch roles at night to become thermometers, helping plants to respond to seasonal changes in temperature.

Dr Philip Wigge explains: “Just as mercury rises in a thermometer, the rate at which phytochromes revert to their inactive state during the night is a direct measure of temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower phytochromes revert to inactivity, so the molecules spend more time in their active, growth-suppressing state. This is why plants are slower to grow in winter”.

Read the paper in Science: Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis.

A fossil ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) leaf with its modern counterpart. Image credit: Gigascience.

In November, a Chinese team published the genome of Ginkgo biloba¸ the oldest extant tree species. Its large (10.6 Gb) genome has previously impeded our understanding of this living fossil, but researchers will now be able to investigate its ~42,000 genes to understand its interesting characteristics, such as resistance to stress and dioecious reproduction, and how it remained almost unchanged in the 270 million years it has existed.

Author Professor Yunpeng Zhao said, “Such a genome fills a major phylogenetic gap of land plants, and provides key genetic resources to address evolutionary questions [such as the] phylogenetic relationships of gymnosperm lineages, [and the] evolution of genome and genes in land plants”.

Read the paper in GigaScience: Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba.

The year ended with another fascinating discovery from a Danish team, who used fluorescent tags and microscopy to confirm the existence of metabolons, clusters of metabolic enzymes that have never been detected in cells before. These metabolons can assemble rapidly in response to a stimulus, working as a metabolic production line to efficiently produce the required compounds. Scientists have been looking for metabolons for 40 years, and this discovery could be crucial for improving our ability to harness the production power of plants.

Read the paper in Science: Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum.

Another amazing year of science! We’re looking forward to seeing what 2017 will bring!

P.S. Check out 2015 Plant Science Round Up to see last year’s top picks!