Leaves display a remarkable range of forms from flat sheets with simple outlines to the cup-shaped traps found in carnivorous plants.

A general question in developmental and evolutionary biology is how tissues shape themselves to create the diversity of forms we find in nature such as leaves, flowers, hearts and wings.

Study of leaves has led to progress in understanding the mechanisms that produce the simpler, flatter forms. But it’s been unclear what lies behind the more complex curved leaf forms of carnivorous plants.

Previous studies using the model species Arabidopsis thaliana which has flat leaves revealed the existence of a polarity field running from the base of the leaf to the tip, a kind of inbuilt cellular compass which orients growth.

To test if an equivalent polarity field might guide growth of highly curved tissues, researchers analysed the cup-shaped leaf traps of the aquatic carnivorous plant Utricularia gibba, commonly known as the humped bladderwort.

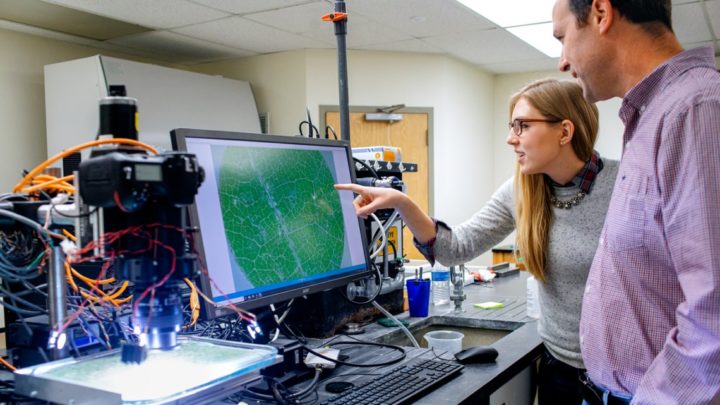

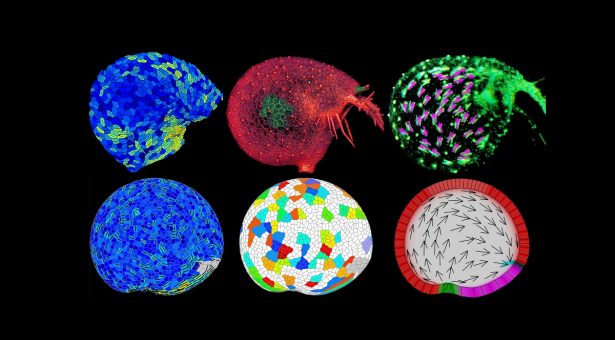

The team of Professor Enrico Coen used a combination of 3D imaging, cell and clonal analysis and computational modelling to understand how carnivorous plant traps are shaped.

These approaches showed how Utricularia gibba traps grow from a near spherical ball of cells into a mature trap capable of capturing prey.

By measuring 3D snapshots of traps at various developmental stages and exploring computational growth models they showed how differential rates and orientations of growth are involved.

The team used fluorescent proteins to monitor cellular growth directions and 3D imaging at different developmental stages to study the changing shape of the trap.

The computational modelling used to account for oriented growth invokes a polarity field comparable to that proposed for Arabidopsis leaf development, except that here it propagates within a curved sheet.

Analysis of the orientation of quadrifid glands, which in Utricularia gibba are used for nutrient absorption, confirmed the existence of the hypothesised polarity field.

The study which appears in the Journal PLOS Biology concludes that simple modulation of mechanisms underlying flat leaf development can also account for shaping of more complex 3D shapes.

One of the lead authors Karen Lee said, “A polarity field orienting growth of tissue sheets may provide a unified explanation behind the development of the diverse range of leaves we find in nature.”

The study, done in collaboration with the group of Minlong Cui at Zhejiang University in China

Read the paper: PLOS Biology

Article source: John Innes Centre

Image credit: Karen Lee, Yohei Koide, John Fozard and Claire Bushell.

This week we spoke to Francisco Gomez and Ammani Kyanam, graduate students in the Soil and Crop Science Department at Texas A&M University, USA. They were part of the organizing committee for the recent Texas A&M Plant Breeding Symposium, a successful meeting run entirely by students at the University.

Francisco Gomez and Ammani Kyanam, part of the student organizing committee of the Plant Breeding Symposium

Could you begin with a brief introduction to the Plant Breeding Symposium held at Texas A&M in February?

Texas A&M University is one of the largest academic and public plant breeding institutions worldwide, which trains breeders in a variety of programs. Every year, students at the University organize the Texas A&M Plant Breeding Symposium, which is part of the DuPont Pioneer series of symposia. The symposium provides a platform for graduate students to bridge the interaction between the public and private sectors and engage in conversations about the grand challenges facing humanity that could be addressed by plant breeding. It’s also a great chance to network with faculty, students, and industry representatives.

Could you tell us more about this theme and how the different sessions were chosen?

We wanted the theme of the meeting to mirror the university’s goal of thinking big to pinpoint solutions to modern global challenges using plant science and breeding. Every member of the committee had the opportunity propose a theme, which were then put to a vote.

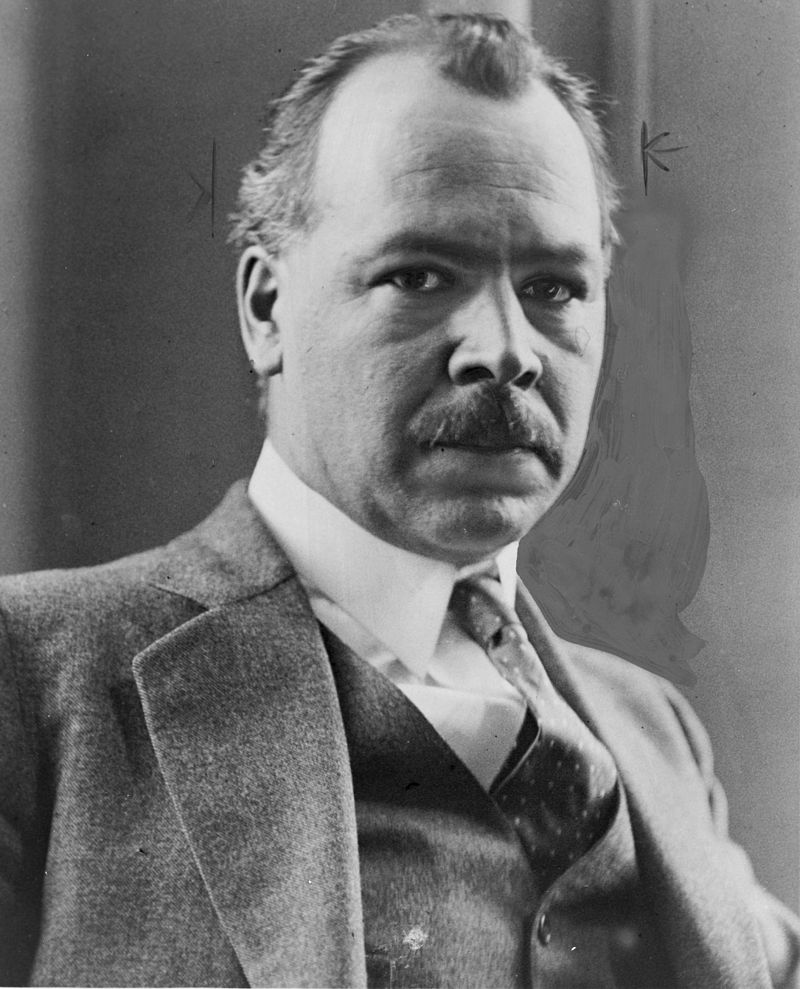

Nikolai Vavilov, a Russian botanist and geneticist, was the inspiration for this year’s symposium. Image credit: Public Domain.

This year’s theme, “The Vavilov Method: Utilizing Genetic Diversity”, celebrated the life and career of Russian botanist Nikolai Vavilov, who identified the centers of origin of cultivated plants. We invited plant scientists and breeders who are applying Vavilov’s ideas through the conservation, collection, and effective utilization of genetic diversity in modern crop breeding programs. This year we also developed a workshop entitled “Where does a breeder go to find genetic diversity?”, which allowed students and faculty to talk about the importance of utilizing genetic diversity in crop improvement and to learn new tools to help them incorporate genetic diversity in breeding programs.

Could you tell us more about how you developed the workshop?

Our aim for the workshop was to engage students and faculty on where we can find genetic diversity, how we can use it, and to include a panel discussion on the challenges and the future of genetic diversity in modern plant breeding programs. As a new value-added event, the workshop was challenging to set up because it required a different set of skills to the rest of the meeting. Once we had an idea of what we wanted, we set up an initial meeting with our speakers where we brainstormed ideas. After several online meetings and e-mails with Professor Paul Gepts (UC Davis), Dr. Colin Khoury (Agricultural Research Service, USDA; check out his recent GPC blog here!), and Professor Susan McCouch (Cornell University), we finalized the structure of the workshop, the layout of the sessions, and the objectives for the speakers. We also had a representative from DivSeek, Dr. Ruth Bastow, on the discussion panel, who contributed to our discussion on future tools for accessing diversity in the future.

How has the symposium grown since the inaugural meeting in 2015?

Every year we want to make the symposium a memorable event, and we want other students and faculty to really get something out of it. We are learning more and more about the students and faculty with these events, particularly in terms of which topics are the most exciting or interesting. The symposium has also grown into a two-day event, with this year’s inclusion of the workshop.

Did you have to overcome any challenges in the organization of the event?

One of our biggest challenges was to secure funding for the event, which is free to attend. To add further value to our event, we wanted to have additional components such as a student research competition and/or workshop, which meant we had to aggressively fundraise from multiple sources. This involved writing a lot of grant proposals both to plant sciences departments across Texas A&M University, as well as to other sources of external funding.

We are grateful to DuPont Pioneer for providing a large amount of the funding. In 2017, we also received sponsorship from the Texas Institute for Genomic Science and Society, Departments of Soil and Crop Sciences, Molecular and Environmental Plant Science, Horticulture, Plant Pathology, and Biology, Texas Grain Sorghum Association, Texas Peanut Producers Board, and Cotton Incorporated. Our beverage sponsor was Pepsi and Kind Snacks was our snack sponsor.

What advice would you give a graduate student trying to organize a similar event?

Plan early and set small goals! Communication is key for a large team to organize such an event. We encourage groups to use Slack or some sort of team work interface. It really helped us to be in constant communication with each other during the months leading up to the symposium.

Could you tell us a little about your own research?

My research (Francisco Gomez) is focused on identifying genomic regions (known as quantitative trait loci; QTLs) associated with mechanical traits that are known to be associated with stem lodging, a major agronomic problem that reduces yields worldwide. My colleague and co-chair, Ammani Kyanam, received her Masters in Plant Breeding in while working in the cotton cytogenetics program in our department. Her research focused on developing genomic tools to facilitate the development of Chromosome Segment Substitution Lines for upland cotton. She is currently mapping QTLs for aphid resistance in sorghum for her Ph.D. You can learn more about the research of our individual committee members at http://plantbreedingsymposium.com/committee/.

How can our readers connect with you?

We have a strong social media presence via Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, where we post event videos, photos and periodical updates. Check them out below!

Facebook: TAMUPBsymposium

Instagram: @pbsymposium

Twitter: @pbsymposium

YouTube: Texas A&M Plant Breeding Symposium

Website: plantbreedingsymposium.com

Email: mailto:pbsymposium@gmail.com

By Lucina Melesio

[MEXICO CITY] An international team of scientists identified a hundred genes that influence adaptation to the latitude, altitude, growing season and flowering time of nearly 4,500 native maize varieties in Mexico and in almost all Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Creole — or native — varieties of maize are derived from improvements made over thousands of years by local farmers, and contain genes that help them adapt to different environments.

“We are now using this analysis to find other genes that are of vital importance to breeders, such as those resistant to extreme heat, frost or drought — environmental conditions associated with climate change and that could affect maize production.”

Sarah Hearne, CIMMYT

“Latin American breeders will be able to use these results to identify native varieties that could contribute to improved adaptation”, Edward Buckler, a Cornell University researcher and co-author of the study published in Nature Genetics (February 6), told SciDev.Net.

The information on the genetic markers described in the study will be available online, said Sarah Hearne, a researcher at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and co-author of the study. “Meanwhile, any breeder can contact us to request information”, she said.

“We are now using this analysis to find other genes that are of vital importance to breeders, such as those resistant to extreme heat, frost or drought — environmental conditions associated with climate change and that could affect maize production”, Hearne said.

Maize ears from CIMMYT’s collection, showing a wide variety of colors and shapes. CIMMYTs germplasm bank contains about 28,000 unique samples of cultivated maize and its wild relatives, teosinte and Tripsacum. These include about 26,000 samples of farmer landracestraditional, locally-adapted varieties that are rich in diversity. The bank both conserves this diversity and makes it available as a resource for breeding.

Photo credit: Xochiquetzal Fonseca/CIMMYT.

Studying native maize varieties is extremely difficult because of their genetic variation. Although domesticated, they are wilder than commercial varieties.

For this study, the researchers cultivated hybrid creole varieties in various environments in Latin America and identified regions of the genome that control growth rates. They looked into where the varieties came from and what genetic features contributed to their growth in that environment.

Hearne added that the research team has initiated a “pre-breeding” programme with a small group of breeders in Mexico. As part of that programme, CIMMYT delivers to breeders materials from its germplasm bank of Creole maize; it also provides molecular information the breeders can use to generate new varieties.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Latin America and Carribean edition.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.

This post was written by Professor Doug Cook (University of California, Davis), the Director of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Climate Resilient Chickpea. His current research spans both model and crop legume systems from a cellular to an ecosystem scale.

The origins of modern human society derive, in large part, from the transition to an agrarian lifestyle that occurred in parallel at multiple locations around the world, including ~10,000 years ago in Mesopotamia*. Early agriculturalists wrought a revolution that would define human trajectory to the current day, domesticating wild plant and animal species into crops and livestock. The wild progenitors of chickpea, for example, were among a handful of Mesopotamian neo-crops, brought from hilly slopes into more fertile and cultivable plains and river valleys. In doing so, these farmers selected a small number of useful traits largely based on natural mutations that made wild forms amenable to agriculture, such as the consistency of flowering, upright growth, and seeds that remained attached to plants rather than dispersing.

Collecting wild chickpea plants, soil, and seed in southeastern Turkey. Image credit: Chickpea Innovation lab.

An unintended consequence of crop domestication was the loss of the vast majority of genetic diversity found in the wild populations. The Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Climate Resilient Chickpea at the University of California, Davis (Chickpea Innovation Lab) documented a ~95% loss of genetic variation from wild species to modern elite varieties. This reduction in genetic variation constrains our ability to adapt the chickpea crop to the range of challenges facing modern agriculture.

The Chickpea Innovation Lab is re-awakening the untapped potential of wild chickpea and directing that potential to solve global problems in agriculture, especially in the developing world. Combining longstanding practices in ecology with the remarkable power of genomics and sophisticated computational methods, we have spanned the gap from the wild systems to cultivated crops. Beginning with the analysis of ~2,000 wild genomes, the simple technology of genetic crosses applied at massive scale has delivered a large and representative suite of wild variation into agricultural germplasm. These traits are now being actively used for phenotyping and breeding in the U.S., India, Ethiopia and Turkey, and our team is currently prospecting for tolerance to drought, heat and cold; increased pest and disease resistance; improved seed nutritional content; nitrogen fixation; plant architecture; and yield.

Visiting Ethiopian student, Sultan Mohammed Yimer investigating disease resistance in wild chickpea. Image credit: Chickpea Innovation lab.

Along the way, the Chickpea Innovation Lab has deposited wild germplasm into the multi-lateral system, providing open access to a treasure trove of genetic variation. The Chickpea Innovation Lab derives support from numerous sponsors whose funds enable the collection, characterization, and utilization of this vital germplasm resource.

International research

A unique strength of the lab is that our diverse sponsorship permits activities ranging from fundamental scientific investigation to applied agricultural research and product development.

An additional objective of the Lab is to train and educate students in the developing world. Towards that end, 18 international and nine domestic students, postdoctoral scientists and visiting faculty have received training in disciplines ranging from computational biology, plant pathology and entomology, to agricultural microbiology, and molecular genetics and breeding.

Harvesting progeny derived by crossing wild and cultivated chickpea plants in Davis, California. Image credit: Chickpea Innovation lab.

* Mesopotamia, literally “between the rivers”, is the region of modern day southeastern Turkey, bounded by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

This article is reposted from the Devex blog with kind permission from the author, Lisa Cornish.

Plant samples in the genebank at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture’s Genetic Resources Unit, at the institution’s headquarters in Colombia. Credit: Neil Palmer / CIAT. Used under license: CC BY-SA 2.0.

It was too dry in the Australian region of Wimmera to produce crops last summer. This year, floods are set to wipe out yields again. Like a number of other regions across the planet, climate change is starting to be felt.

“It’s like this every year somewhere,” said Sally Norton, head of the Australian Grains Genebank, which stores diverse genetic material for plant breeding and research.

For Norton and many of her colleagues in agricultural genetics, the picture is increasingly clear: The variety of crops used today are not able to withstand the changing conditions and changes expected in the future.

Australia’s biodiversity may offer some help, according to discussions at the recent International Genebank Managers Annual General Meeting held in Horsham, Victoria. The gathering, which brings together 11 countries, focused on how to better conserve seeds, build databases to manage collections, boost capacity across the world and fill gaps in genebanks.

Researchers are particularly interested in crop wilds, “the ancestors of our domesticated crops,” Marie Haga, executive director of the The Crop Trust, explained to Devex. Australia is one of the richest sources of these seeds. “It’s like the wolf being the ancestor to our domesticated dogs. Crop wild relatives have traits that we have lost in the domestication process — they might need less water, might live in unfriendly conditions, may be resistant to pests and diseases.”

As climate change continues to batter agricultural yields, crop wild relatives could provide resilience. The seeds give breeders and farmers new options of plant varieties with traits to withstand a variety of conditions based on the harsh climates they are found — drought, fire, flood, poor soil, high salinity.

For Haga, crop wild relatives are a solution for food security. “The challenge is that many of the varieties widely used in modern agriculture are very vulnerable, because we have been breeding on the same line and they are adapted to very specific environment,” Haga said. Varieties that flourish today, she said, could wither as the climate fluctuates.

“Utilization of the natural diversity of crops is key to the future,” she said. “The climate is rapidly changing and we need to feed a growing population with more nutritious food. It is very hard to see how we can do this unless we go back to the building blocks of agriculture.”

Norton agreed: “Crop wild relatives have an amazing adaptability to changing conditions,” she told Devex. “When we talk about food security, we are talking about getting varieties in farm paddocks that have greater resilience to extreme conditions. It may not be the highest yield, but you are going to get something from this crop.”

Crop wild relatives have so far been underutilized in the research and breeding process of crops.

“We have this fabulous natural diversity out there including 125,000 varieties of wheat and 200,000 varieties of rice.” Haga said. “We have not at all unlocked the potential of these crops.”

One reason is a dearth of research. “Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Collecting, Protecting and Preparing Crop Wild Relatives,” a 10-year project led by Haga to ensure long-term conservation of crop wild relatives, conducted a global survey of distribution and conservation and found that of 1,076 known wild relatives for 81 crops, more than 95 percent are insufficiently represented in genebanks and 29 percent are completely missing. They are missing purely due to the fact that they have yet to be collected.

“Genebank managers are generally open to include crop wild relatives in their collections.” Haga said. “It’s just quite simply that not enough work has been done in this area and the full potential is yet to be realized,” she said.

At the moment, seeds are being collected in 25 countries around the world as part of the crop wild relative project, but it is Australia that has been identified as one of the richest sources for crop wild relatives in the world. Because of the continent’s low population density and vast, undisturbed natural environment, a wide variety of species have been conserved, said Norton.

Australia holds significant diversity of wild relatives of rice, sorghum, pigeon pea, banana, sweet potato and eggplant currently missing from global collections, according to research by the Australian Seed Bank Partnership. Forty species have been prioritized for collection with high hopes that they will enable crops to withstand the harsh environmental conditions in which Australian species are found.

There are still many areas of Australia yet to be surveyed, and the full extent of its agricultural riches may yet to be tapped.

Australian researchers will play an important role in pre-breeding local species of wild relatives to improve their use in breeding programs. Crop wild relatives have historically been used in a variety of crops including synthetic wheat, but Australian native wild relatives have been harder to include in the breeding process.

“In the next 10 to 15 years it would be surprising if there is not something coming out that hasn’t got a component of Australian native wild relative in it,” Norton said who is currently involved in the collection of Australian crop wild relatives.

There is an urgency to collect crop wild relatives. Not only are wild species needed now to support changing environmental conditions affecting crops and farming, urbanization is putting crop wild relatives at risk of disappearing.

“We need to collect these sooner rather than later,” Norton told Devex. “Urbanization has a big impact on any native environment, let alone crop wild relatives. We know what species on our target list are more threatened than others — urbanization, flooding and fire are all risks to their security. We certainly have a priority list of species to collect and we need to make sure we target the ones that are under threat first.”

Once the varieties are conserved, breeders and farmers will need to be convinced to start using crop wild relatives. Many are already on board. “Most breeders understand these wild relatives have great potential,” Haga said.

Still, wild relatives can be difficult to work with and produce a lower yield. Haga expects there to be some reluctance, though limited.

“The understanding of the need is increasing and we feel very confident that this material will be used and some of them may be the game changer we are looking for,” she said.

Haga’s 10-year project on crop wild relatives is halfway complete. They are nearing the end of the collection phase and entering the pre-breeding process, before they are able to breed and deliver new species to farmers.

Australian support for the program includes an agreement for additional amount of $5 million. That comes on top of previous support of $21.2 million to the Crop Diversity Endowment Fund, which supports crop diversity globally and with a focus on the Indo-Pacific. Brazil, Chile, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the United States are among other supporters of the endowment fund that hopes to reach $850 million. In Australia, further resources are still required to fund and support better seed collection at home.

Globally, plans for crop wild relatives includes raising greater awareness of their potential and importance.

“We have a big job to do to create awareness of the important of crop diversity generally and crop wild relatives specifically,” Haga said. “We have been speaking for years about biodiversity in birds and fish and a range of other animals, but we have talked very little about conserving the diversity of crops. I will fight for all types of diversity, but especially plants.”

This article is reposted from the Devex blog with kind permission from the author, Lisa Cornish.

By Hannes Dempewolf

We at the Global Crop Diversity Trust care about wildlings! No, not the people beyond The Wall, but the wild cousins of our domesticated crops. By collecting, conserving and using wild crop relatives, we hope to be able to adapt agriculture to climate change. This project is funded by the Government of Norway, in partnership with the Millennium Seed Bank at Kew in the UK, and many national and international research institutes around the world.

The first step of this project was to map and analyze the distribution patterns of hundreds of crop wild relatives. Next, we identified global priorities for collecting, and are now providing support to our national partners to collect these wild species and use them in pre-breeding efforts. An example of a crop we have already started pre-breeding is eggplant (aubergine). This crop, important in developing countries, has many wild relatives, which we are using to develop varieties that can better withstand abiotic stresses and variable environments.

More recently we have started a discussion with the crop science community on how best to share our data and information about these species, and genetic resources more generally. This discourse that was at the heart of what has now become the DivSeek Initiative, a Global Plant Council initiative that you can read more about in this GPC blog post by Gurdev Khush.

Why should you care?

Good question. I couldn’t possibly answer it better than Sandy Knapp, one of the Project’s recent reviewers, who speaks in the video below.

One of the great leaders in the field, Jack Harlan, also recognized their immense value: “When the crop you live by is threatened you will turn to any source of relief you can find. In most cases, it is the wild relatives that salvage the situation, and we can point very specifically to several examples in which genes from wild relatives stand between man and starvation or economic ruin.”

Wild rice, Oryza officinalis, is being used to adapt commercial rice cultivars to climate change. Photo credit: IRRI photos, used under Creative Commons License 2.0

Crop wild relatives have indeed been used for many decades to improve crops and their value is well recognized by breeders. This is increasingly true also for abiotic stress tolerances, particularly relevant if we care about adapting our agricultural systems to climate change. One such example is the use of a wild rice (Oryza officinalis) to change the flowering time of the rice cultivar Koshihikari (Oryza sativa) to avoid the hottest part of the day.

Share the care

Fostering the community of those who care about crop wild relatives is an important objective of the project. We make sure that all the germplasm collected by partners is accessible to the global community for research and breeding, within the framework of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (the ‘Plant Treaty’). The project invests into building capacity into collecting: it’s not as simple a process as it may sound. The following shows the training in collection in Uganda:

We also put a heavy emphasis on technology transfer and the development of lasting partnerships in all of the pre-breeding projects we support.

The only way we can safeguard and reap the benefits of the genetic diversity of crop wild relatives over the long term is by supporting a vibrant, committed community. We hope you agree, and encourage you to get in touch via cropwildrelatives@croptrust.org.

To find out more about the Crop Trust and how you can take action to help conserve crop diversity for food security, please visit our webpage. For more information about the Crop Wild Relatives project, please visit www.cwrdiversity.org.