At July’s New Breeding Technologies workshop held in Gothenburg, Sweden, Dr. Staffan Eklöf, Swedish Board of Agriculture, gave us an insight into their analysis of European Union (EU) regulations, which led to their interpretation that some gene-edited plants are not regulated as genetically modified organisms. We speak to him here on the blog to share the story with you.

Could you begin with a brief explanation of your job, and the role of the Competent Authority for GM Plants / Swedish Board of Agriculture?

I am an administrative officer at the Swedish Board of Agriculture (SBA). The SBA is the Swedish Competent authority for most GM plants and ensures that EU regulations and national laws regarding these plants are followed. This includes issuing permits.

You reached a key decision on the regulation of some types of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants. Before we get to that, could you start by explaining what led your team to start working on this issue?

It started when we received questions from two universities about whether they needed to apply for permission to undertake field trials with some plant lines modified using CRISPR/Cas9. The underlying question was whether these plants are included in the gene technology directive or not. According to the Swedish service obligation for authorities, the SBA had to deliver an answer, and thus had to interpret the directive on this point.

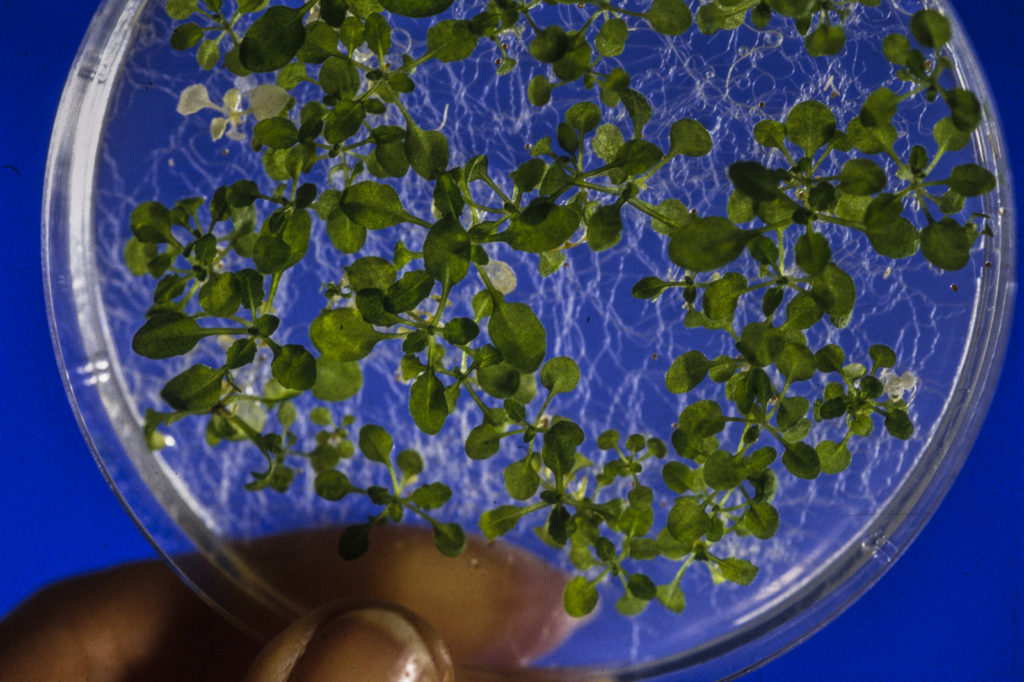

Image credit: INRA, Jean Weber. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Could you give a brief overview of Sweden’s analysis of the current EU regulations that led to your interpretation that some CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants are not covered by this legislation?

The following simplification describes our interpretation pretty well; if there is foreign DNA in the plants in question, they are regulated. If not, they are not regulated.

Our interpretation touches on issues such as what is a mutation and what is a hybrid nucleic acid. The first issue is currently under analysis in the European Court of Justice. Other ongoing initiatives in the EU may also change the interpretations we made in the future, as the directive is common for all member states in the EU.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a powerful tool that can result in plants with no trace of transgenic material, so it is impossible to tell whether a particular mutation is natural. How did this influence your interpretation?

We based our interpretation on the legal text. The fact that one cannot tell if a plant without foreign DNA is the progeny of a plant that carried foreign DNA or the result of natural mutation strengthened the position that foreign DNA in previous generations should not be an issue. It is the plant in question that should be the matter for analysis.

Image credit: Frost Museum. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Does your interpretation apply to all plants generated using CRISPR-Cas9, or a subset of them?

It applies to a subset of these gene-edited plants. CRISPR/Cas9 is a tool that can be used in many different ways. Plants carrying foreign DNA are still regulated, according to our interpretation.

What does your interpretation mean for researchers working on CRISPR-Cas9, or farmers who would like to grow gene-edited crops in Sweden?

It is important to note that, with this interpretation, we don’t remove the responsibility of Swedish users to assess whether or not their specific plants are included in the EU directive. We can only tell them how we interpret the directive and what we request from the users in Sweden. Eventually I think there will be EU-wide guidelines on this matter. I should add that our interpretation is also limited to the types of CRISPR-modified plants described in the letters from the two universities.

Will gene-edited crops be grown in Europe in the future? Image credit: Richard Beatson. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

We are currently waiting for the EU to declare whether CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants will be regulated in Europe. Have policymakers in other European countries been in contact with you regarding Sweden’s decision process?

Yes, there is a clear interest; for example, Finland handled a very similar case. Other European colleagues have also shown an interest.

What message would you like plant scientists to take away from this interview? If you could help them to better understand one aspect of policymaking, what would it be?

Our interpretation is just an interpretation and as such, it is limited and can change as a result of what happens; for example, what does not require permission today may do tomorrow. Bear this in mind when planning your research and if you are unsure, it is better to ask. Moreover, even if the SBA (or your country’s equivalent) can’t request any information about the cultivation of plants that are not regulated, it is good to keep us informed.

I think it is vital that legislation meets reality for any subject. It is therefore good that pioneers drive us to deal with difficult questions.

This week’s blog was written by Dr Craig Cormick, the Creative Director of ThinkOutsideThe. He is one of Australia’s leading science communicators, with over 30 years’ experience working with agencies such as CSIRO, Questacon and Federal Government Departments.

So what do you think CRISPR cabbage might taste like? CRISPR-crispy? Altered in some way?

Participants at the recent Society for Experimental Biology/Global Plant Council New Breeding Technologies workshop in Gothenburg, Sweden, had a chance to find out, because in Sweden CRISPR-produced plants are not captured by the country’s GMO regulations and can be produced.

Professor Stefan Jansson, one of the workshop organizers, has grown the CRISPR cabbage (discussed in his blog for GPC!) and not only had it included on the menu of the workshop dinner, but also had samples for participants to take away. Some delegates were keen to pick up the samples while others were unsure how their own country’s regulatory rules would apply to them

That’s really CRISPR-edited cabbage on the menu. #SEBNBT17 Thanks Stefan Jansson pic.twitter.com/85KtpaTHWi

— Wayne Parrott (@ProfParrott) July 7, 2017

The uncertainty some delegates felt about the legality of taking a CRISPR cabbage sample home was a good demonstration of the diversity of regulations that apply – or may apply – to new breeding technologies, such as CRISPR and gene editing – and there was considerable discussion at the workshop on how European Union regulations and court rulings may play out, affecting both the development and export/import of plants and foods produced by the new technologies.

A lack of certainty has meant many researchers are unable to determine whether their work will need to be subjected to costly and time-consuming regulations or not.

The need for new breeding technologies was made clear at the workshop, which was attended by 70 people from 17 countries, with presentations on the need to double our current food production to feed the world in 2050 and reduce crop losses caused by problems such as viruses, which deplete crops by 10–15%.

The two-day workshop, held in early July, looked at a breadth of issues, including community attitudes, gene editing success stories, and tools and resources. But discussions kept coming back to regulation.

Regulations of gene technologies were largely developed 20 years ago or so, for different technologies than now exist, and as a result are not clear enough for researchers to determine whether different gene editing technologies they are working on may be governed by them or not.

The diversity of regulations is also going to be an issue, for some countries may allow different gene editing technologies, but others may not allow products developed using them to be imported.

That led to the group beginning to develop a statement that captured the feeling of the workshop, which, when complete, it is hoped will be adopted by relevant agencies around the world to develop their own particular positions on gene editing technologies. It would be a huge benefit to have a coherent and common line in an environment of mixed regulations in mixed jurisdictions.

And as to the initial question of what CRISPR cabbage tastes like – just like any cabbage you might buy at your local supermarket or farmers market, of course – since it is really no different.

#SEBNBT17 looks like normal cabbage but this gene edited! pic.twitter.com/i5pSy5c4bC

— GARNet (@GARNetweets) July 7, 2017

Want to read more about CRISPR? Check out our interview with Prof. Stefan Jansson or our introduction to CRISPR from Dr Damiano Martignago.

Another fantastic year of discovery is over – read on for our 2016 plant science top picks!

A Zostera marina meadow in the Archipelago Sea, southwest Finland. Image credit: Christoffer Boström (Olsen et al., 2016. Nature).

The year began with the publication of the fascinating eelgrass (Zostera marina) genome by an international team of researchers. This marine monocot descended from land-dwelling ancestors, but went through a dramatic adaptation to life in the ocean, in what the lead author Professor Jeanine Olsen described as, “arguably the most extreme adaptation a terrestrial… species can undergo”.

One of the most interesting revelations was that eelgrass cannot make stomatal pores because it has completely lost the genes responsible for regulating their development. It also ditched genes involved in perceiving UV light, which does not penetrate well through its deep water habitat.

Read the paper in Nature: The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea.

BLOG: You can find out more about the secrets of seagrass in our blog post.

Plants are known to form new organs throughout their lifecycle, but it was not previously clear how they organized their cell development to form the right shapes. In February, researchers in Germany used an exciting new type of high-resolution fluorescence microscope to observe every individual cell in a developing lateral root, following the complex arrangement of their cell division over time.

Using this new four-dimensional cell lineage map of lateral root development in combination with computer modelling, the team revealed that, while the contribution of each cell is not pre-determined, the cells self-organize to regulate the overall development of the root in a predictable manner.

Watch the mesmerizing cell division in lateral root development in the video below, which accompanied the paper:

Read the paper in Current Biology: Rules and self-organizing properties of post-embryonic plant organ cell division patterns.

In March, a Spanish team of researchers revealed how the anti-wilting molecular machinery involved in preserving cell turgor assembles in response to drought. They found that a family of small proteins, the CARs, act in clusters to guide proteins to the cell membrane, in what author Dr. Pedro Luis Rodriguez described as “a kind of landing strip, acting as molecular antennas that call out to other proteins as and when necessary to orchestrate the required cellular response”.

Read the paper in PNAS: Calcium-dependent oligomerization of CAR proteins at cell membrane modulates ABA signaling.

*If you’d like to read more about stress resilience in plants, check out the meeting report from the Stress Resilience Forum run by the GPC in coalition with the Society for Experimental Biology.*

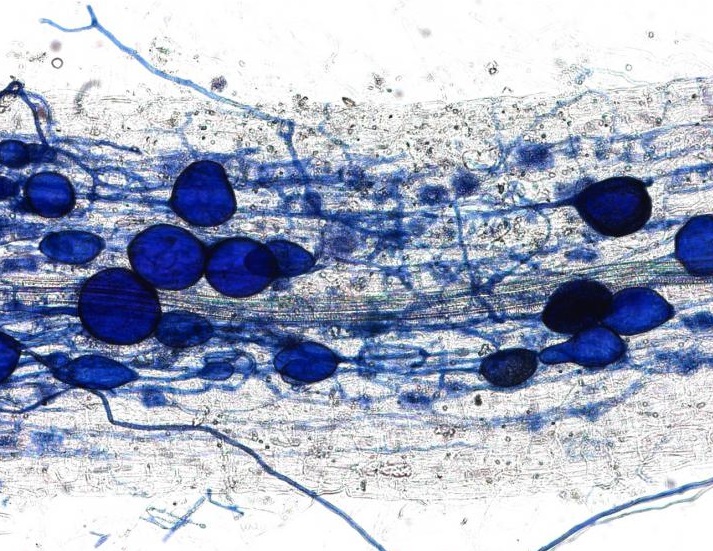

This plant root is infected with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Image credit: University of Zurich.

In April, we received an amazing insight into the ‘decision-making ability’ of plants when a Swiss team discovered that plants can punish mutualist fungi that try to cheat them. In a clever experiment, the researchers provided a plant with two mutualistic partners; a ‘generous’ fungus that provides the plant with a lot of phosphates in return for carbohydrates, and a ‘meaner’ fungus that attempts to reduce the amount of phosphate it ‘pays’. They revealed that the plants can starve the meaner fungus, providing fewer carbohydrates until it pays its phosphate bill.

Author Professor Andres Wiemsken explains: “The plant exploits the competitive situation of the two fungi in a targeted manner, triggering what is essentially a market-based process determined by cost and performance”.

Read the paper in Ecology Letters: Options of partners improve carbon for phosphorus trade in the arbuscular mycorrhizal mutualism.

The transition of ancient plants from water onto land was one of the most important events in our planet’s evolution, but required a massive change in plant biology. Suddenly plants risked drying out, so had to develop new ways to survive drought.

In May, an international team discovered a key gene in moss (Physcomitrella patens) that allows it to tolerate dehydration. This gene, ANR, was an ancient adaptation of an algal gene that allowed the early plants to respond to the drought-signaling hormone ABA. Its evolution is still a mystery, though, as author Dr. Sean Stevenson explains: “What’s interesting is that aquatic algae can’t respond to ABA: the next challenge is to discover how this hormone signaling process arose.”

Read the paper in The Plant Cell: Genetic analysis of Physcomitrella patens identifies ABSCISIC ACID NON-RESPONSIVE, a regulator of ABA responses unique to basal land plants and required for desiccation tolerance.

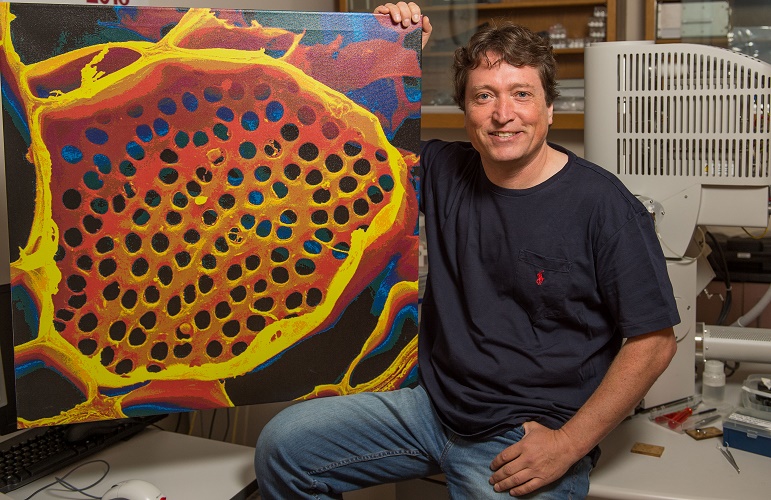

Professor Michael Knoblauch shows off a microscope image of phloem tubes. Image credit: Washington State University.

Sometimes revisiting old ideas can pay off, as a US team revealed in June. In 1930, Ernst Münch hypothesized that transport through the phloem sieve tubes in the plant vascular tissue is driven by pressure gradients, but no-one really knew how this would account for the massive pressure required to move nutrients through something as large as a tree.

Professor Michael Knoblauch and colleagues spent decades devising new methods to investigate pressures and flow within phloem without disrupting the system. He eventually developed a suite of techniques, including a picogauge with the help of his son, Jan, to measure tiny pressure differences in the plants. They found that plants can alter the shape of their phloem vessels to change the pressure within them, allowing them to transport sugars over varying distances, which provided strong support for Münch flow.

Read the paper in eLife: Testing the Münch hypothesis of long distance phloem transport in plants.

BLOG: We featured similar work (including an amazing video of the wound response in sieve tubes) by Knoblauch’s collaborator, Dr. Winfried Peters, on the blog – read it here!

Preserved remains of rope, seeds, reeds and pellets (left), and a desiccated barley grain (right) found at Yoram Cave in the Judean Desert. Credit: Uri Davidovich and Ehud Weiss.

In July, an international and highly multidisciplinary team published the genome of 6,000-year-old barley grains excavated from a cave in Israel, the oldest plant genome reconstructed to date. The grains were visually and genetically very similar to modern barley, showing that this crop was domesticated very early on in our agricultural history. With more analysis ongoing, author Dr. Verena Schünemann predicts that “DNA-analysis of archaeological remains of prehistoric plants will provide us with novel insights into the origin, domestication and spread of crop plants”.

Read the paper in Nature Genetics: Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley.

BLOG: We interviewed Dr. Nils Stein about this fascinating work on the blog – click here to read more!

Another exciting cereal paper was published in August, when an Australian team revealed that C4 photosynthesis occurs in wheat seeds. Like many important crops, wheat leaves perform C3 photosynthesis, which is a less efficient process, so many researchers are attempting to engineer the complex C4 photosynthesis pathway into C3 crops.

This discovery was completely unexpected, as throughout its evolution wheat has been a C3 plant. Author Professor Robert Henry suggested: “One theory is that as [atmospheric] carbon dioxide began to decline, [wheat’s] seeds evolved a C4 pathway to capture more sunlight to convert to energy.”

Read the paper in Scientific Reports: New evidence for grain specific C4 photosynthesis in wheat.

Professor Stefan Jansson cooks up “Tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables”. Image credit: Stefan Jansson.

September marked an historic event. Professor Stefan Jansson cooked up the world’s first CRISPR meal, tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables (genome-edited cabbage). Jansson has paved the way for CRISPR in Europe; while the EU is yet to make a decision about how CRISPR-edited plants will be regulated, Jansson successfully convinced the Swedish Board of Agriculture to rule that plants edited in a manner that could have been achieved by traditional breeding (i.e. the deletion or minor mutation of a gene, but not the insertion of a gene from another species) cannot be treated as a GMO.

Read more in the Umeå University press release: Umeå researcher served a world first (?) CRISPR meal.

BLOG: We interviewed Professor Stefan Jansson about his prominent role in the CRISPR/GM debate earlier in 2016 – check out his post here.

*You may also be interested in the upcoming meeting, ‘New Breeding Technologies in the Plant Sciences’, which will be held at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, on 7-8 July 2017. The workshop has been organized by Professor Jansson, along with the GPC’s Executive Director Ruth Bastow and Professor Barry Pogson (Australian National University/GPC Chair). For more info, click here.*

Phytochromes help plants detect day length by sensing differences in red and far-red light, but a UK-Germany research collaboration revealed that these receptors switch roles at night to become thermometers, helping plants to respond to seasonal changes in temperature.

Dr Philip Wigge explains: “Just as mercury rises in a thermometer, the rate at which phytochromes revert to their inactive state during the night is a direct measure of temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower phytochromes revert to inactivity, so the molecules spend more time in their active, growth-suppressing state. This is why plants are slower to grow in winter”.

Read the paper in Science: Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis.

A fossil ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) leaf with its modern counterpart. Image credit: Gigascience.

In November, a Chinese team published the genome of Ginkgo biloba¸ the oldest extant tree species. Its large (10.6 Gb) genome has previously impeded our understanding of this living fossil, but researchers will now be able to investigate its ~42,000 genes to understand its interesting characteristics, such as resistance to stress and dioecious reproduction, and how it remained almost unchanged in the 270 million years it has existed.

Author Professor Yunpeng Zhao said, “Such a genome fills a major phylogenetic gap of land plants, and provides key genetic resources to address evolutionary questions [such as the] phylogenetic relationships of gymnosperm lineages, [and the] evolution of genome and genes in land plants”.

Read the paper in GigaScience: Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba.

The year ended with another fascinating discovery from a Danish team, who used fluorescent tags and microscopy to confirm the existence of metabolons, clusters of metabolic enzymes that have never been detected in cells before. These metabolons can assemble rapidly in response to a stimulus, working as a metabolic production line to efficiently produce the required compounds. Scientists have been looking for metabolons for 40 years, and this discovery could be crucial for improving our ability to harness the production power of plants.

Read the paper in Science: Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum.

Another amazing year of science! We’re looking forward to seeing what 2017 will bring!

P.S. Check out 2015 Plant Science Round Up to see last year’s top picks!

This week’s blog post was written by Dr Damiano Martignago, a genome editing specialist at Rothamsted Research.

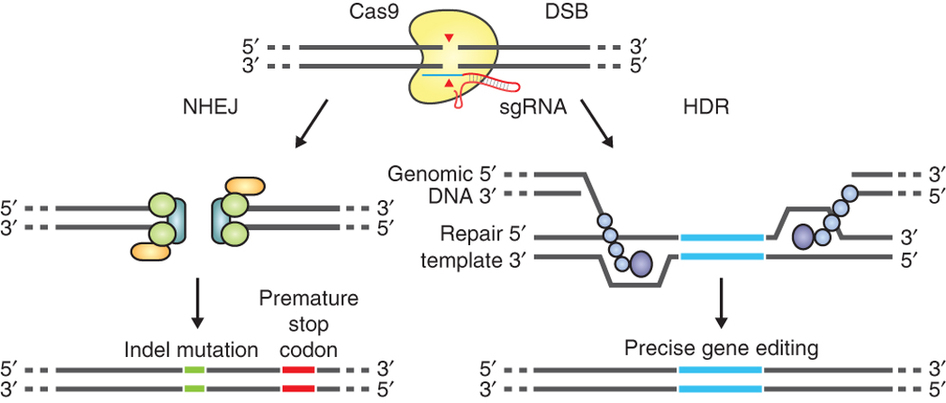

Genome editing technologies comprise a diverse set of molecular tools that allow the targeted modification of a DNA sequence within a genome. Unlike “traditional” breeding, genome editing does not rely on random DNA recombination; instead it allows the precise targeting of specific DNA sequences of interest. Genome editing approaches induce a double strand break (DSB) of the DNA molecule at specific sites, activating the cell’s DNA repair system. This process could be either error-prone, thus used by scientists to deactivate “undesired” genes, or error-free, enabling target DNA sequences to be “re-written” or the insertion of DNA fragments in a specific genomic position.

The most promising among the genome editing technologies, CRISPR/Cas9, was chosen as Science’s 2015 Breakthrough of the Year. Cas9 is an enzyme able to target a specific position of a genome thanks to a small RNA molecule called guide RNA (gRNA). gRNAs are easy to design and can be delivered to cells along with the gene encoding Cas9, or as a pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA protein-RNA complex. Once inside the cell, Cas9 cuts the target DNA sequence homologous to the gRNAs, producing DSBs.

The guide RNA (sgRNA) directs Cas9 to a specific region of the genome, where it induces a double-strand break in the DNA. On the left, the break is repaired by non-homologous-end joining, which can result in insertion/deletion (indel) mutations. On the right, the homologous-directed recombination pathway creates precise changes using a supplied template DNA. Credit: Ran et al. (2013). Nature Protocols.

Together with the increased data availability on crop genomes, genome editing techniques such as CRISPR are allowing scientists to carry out ambitious research on crop plants directly, building on the knowledge obtained during decades of investigation in model plants.

The concept of CRISPR was first tested in crops by generating cultivars that are resistant to herbicides, as this is an easy trait to screen for and identify. One of the first genome-edited crops, a herbicide-resistant oilseed rape produced by Cibus, has already been grown and harvested in the USA in 2015.

Researchers used CRISPR to engineer a wheat variety resistant to powdery mildew (shown here), a major disease of this crop. Image credit: NY State IPM Program. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Using CRISPR, scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences produced a wheat variety resistant to powdery mildew, one of the major diseases in wheat. Similarly, another Chinese research group exploited CRISPR to produce a rice line with enhanced rice blast resistance that will help to reduce the amount of fungicides used in rice farming. CRISPR/Cas9 has also been already applied to maize, tomato, potato, orange, lettuce, soybean and other legumes.

Genome editing could also revolutionize the management of viral plant disease. The CRISPR/Cas9 system was originally discovered in bacteria, where it provided them with molecular immunity against viruses, but it can also be moved into plants. Scientists can transform plants to produce the Cas9 and gRNAs that target viral DNA, reducing virus accumulation; alternatively, they can suppress those plant genes that are hijacked by the virus to mediate its own diffusion in the plants. Since most plants are defenseless against viruses and there are no chemical controls available for plant viruses, the main method to stop the spread of these diseases is still the destruction of the infected plant. For the first time in history, scientists have an effective weapon to fight back against plant viruses.

The cassava brown streak disease virus can destroy cassava crops, threatening the food security of the 300 million people who rely on this crop in Africa. Image credit: Katie Tomlinson (for more on this topic, read her blog here).

Genome editing will be particularly useful in the genetic improvement of many crops that are propagated mainly by vegetative reproduction, and so very difficult to improve by traditional breeding methods involving crossing (e.g. cassava, banana, grape, potato). For example, using TALENs, scientists from Cellectis edited a potato line to minimize the accumulation of reducing sugars that may be converted into acrylamide (a possible carcinogen) during cooking.

One of the hypothesized risks of using CRISPR/Cas9 is the potential targeting of undesired DNA regions, called off-targets. It is possible to limit the potential for off-targets by designing very specific gRNAs, and all of the work published so far either did not detect any off-targets or, if detected, they occurred at a very low frequency. The number of off-target mutations produced by CRISPR/Cas9 is therefore minimal, especially if compared with the widely accepted random mutagenesis of crops used in plant breeding since the 1950s.

Genome editing is interesting from a regulatory point of view too. After obtaining the desired heritable mutation using CRISPR/Cas9, it is possible to remove the CRISPR/Cas9 integrated vectors from the genome using simple genetic segregation, leaving no trace of the genome modification other than the mutation itself. This means that some countries (including the USA, Canada, and Argentina) consider the products of genome editing on a case-by-case basis, ruling that a crop is non-GM when it contains gene combinations that could have been obtained through crossing or random mutation. Many other countries are yet to issue an official statement on CRISPR, however.

Recently, scientists showed that is possible to edit the genome of plants without adding any foreign DNA and without the need for bacteria- or virus-mediated plant transformation. Instead, a pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is delivered to plant cells in vitro, which can edit the desired region of the genome before being rapidly degraded by the plant endogenous proteases and nucleases. This non-GM approach can also reduce the potential of off-target editing, because of the minimal time that the RNP is present inside the cell before being degraded. RNP-based genome editing has been already applied to tobacco plants, rice, and lettuce, as well as very recently to maize.

In conclusion, genome editing techniques, and CRISPR/Cas9 in particular, offers scientists and plant breeders a flexible and relatively easy approach to accelerate breeding practices in a wide variety of crop species, providing another tool that we can use to improve food security in the future.

For more on CRISPR, check out this recent TED Talk from Ellen Jorgensen:

Dr Damiano Martignago is a plant molecular biologist who graduated from Padua University, Italy, with a degree in Food Biotechnology in 2009. He obtained his PhD in Biology at Roma Tre University in 2014. His experience with CRISPR/Cas9 began in the lab of Prof. Fabio Fornara (University of Milan), where he used CRISPR/Cas9 to target photoperiod genes of interest in rice and generate mutants that were not previously available. He recently moved to Rothamsted Research, UK, where he works as Genome Editing Specialist, transferring CRISPR/Cas9 technology to hexaploid bread wheat with the aim of improving the efficiency of genome editing in this crop. He is actively involved with AIRIcerca (International Association of Italian Scientists), disseminating and promoting scientific news.

This week we speak to Professor Stefan Jansson, Umeå University, Sweden, who is the President of one of the Global Plant Council member organizations, the Scandinavian Plant Physiology Society (SPPS). He tells us more about his fascinating work, his prominent role in the GM debate, and his thoughts on the work of the SPPS and GPC, both now and in the future.

Could you tell us a little about your areas of research interest?

I have worked on (too) many things within plant science, but now I am focused on two subjects: “How do trees know that it is autumn?”, and “How can spruce needles stay green in the winter?” We use several approaches to answer these questions, including genetics, genomics, bioinformatics, biochemistry and biophysics.

Your ground-breaking work on CRISPR led to you being awarded the Forest Biotechnologist of the Year award by the Institute of Forest Biosciences. Could you tell us more about this work, and the role you have played in the GM debate?

In our work on photosynthetic light harvesting, we have generated and/or analyzed different lines lacking an important regulatory protein; PsbS. PsbS mutants resulting from treatment with radiation or chemical mutagens can be grown anywhere without restriction, but those that are genetically modified by the insertion of disrupting ‘T-DNA’ are, in reality, forbidden to be grown. For years, I, and many other scientists, have pointed out that it does not make sense for plants with the same properties to be treated so differently by legislators. In science we treat such plants as equivalents; when we publish our results we could be required to confirm that the correct gene was investigated by using an additional T-DNA gene knock-out line or an RNAi plant (RNA interference, where inserted RNA blocks the production of a particular protein), but in the legislation they and the ‘traditionally mutated’ plants are opposites.

This has been the situation for many years, but it has been impossible to change. To challenge this, we set up an experiment using a targeted gene-editing approach called CRISPR/Cas9 to make a deletion in the PsbS gene, which resulted in a plant with a non-functional PsbS gene but no residual T-DNA. We asked the Swedish competent authority if this would be treated as a GM plant or not, arguing that it is impossible to know if it is a ‘traditional’ deletion mutant or a gene-edited mutant. In the end, the authority said that, according to their interpretation of the law, this cannot be treated as a GMO.

If this interpretation is also used in other countries, plant breeders will have access to gene-editing techniques to aid them in their work to generate new varieties, which would otherwise not be a possibility. The reason we did this was to provide the authorities with a concrete case, and one which was not linked to a company or commercial crop but rather something that everyone would realize could only be important for basic science. Therefore most of the arguments that are used against GMOs could not be used, and this should be a step forward in the debate.

You are the President of the Scandinavian Plant Physiology Society, one of the Global Plant Council member organizations. Could you briefly outline the work of the SPPS?

You are the President of the Scandinavian Plant Physiology Society, one of the Global Plant Council member organizations. Could you briefly outline the work of the SPPS?

We support plant scientists – not only plant physiologists – in the Nordic countries, organize meetings, publish a journal (Physiologia Plantarum), etc.

What are the most important benefits that SPPS members receive?

This is an issue that we discuss a lot in the society right now. Only a limited fraction of Nordic plant scientists are members – obviously are the benefits not large enough – and this is something that we intend to change in the coming years. We think, for example, that we need to be a better platform for networking between researchers and research centers, and have a lot of ideas that we would like to implement.

How does the GPC benefit the SPPS?

Although there are country- and region-specific issues important for plant scientists, the biggest issues are global. The arguments why we need plant science are basically the same whether you are a plant scientist in Umeå or Ouagadougou, therefore we all benefit from a global plant organization.

What do you see as important roles for the future of the GPC, both for SPPS and the wider community?

This is quite clear to me: we will contribute to saving the planet.

What advice would you give to early career researchers in plant science?

Your curiosity is your biggest asset, so take good care of it.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

The challenge for the GPC is clearly to get enough resources to be able to fulfil its very worthwhile ambitions. GPC has made a good start: the vision is clear and the roadmap is there, which are two prerequisites, but additional resources are needed to employ people to realize these ambitions, build upon current successes, and perform the important activities. It is easy to say that if we all contribute with a small fraction of our time that would be sufficient, but we all have may other obligations and commitments, and a few dedicated people are needed in all organizations.

Established GM technologies are far from perfect

The first genetically modified (GM) crops were approved for commercial use in 1994, and GM crops are now grown on over 180 million hectares across 29 countries. The most used forms of genetic modification are systems that result in herbicide resistance or expression of the Bt toxin in maize and cotton to provide protection against pests such as the European corn borer. These systems both require few novel genes to be introduced to the plant, and allow more efficient use of herbicides and pesticides, both of which are harmful to the environment and human health. Current systems of genetic modification usually involve

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is used to genetically engineer plants in the lab. In nature this bacteria uses its ability to alter plant DNA to cause tumours. Image by Jacinta Lluch Valero used under Creative Commons 2.0.

the use of Agrobacterium vectors, direct transformation by DNA uptake into the plant protoplast, or bombardment with gold particles covered in DNA. However, current systems of transformation are far from perfect. Many beneficial traits such as disease resistance require stacking of multiple genes, something that is difficult with current transformation systems. Furthermore, it is essential that transgenes are positioned correctly within the host genome. Current systems of genetic modification can insert genes into the ‘wrong’ place, disrupting function of endogenous genes or having implications for down or upstream processes. An additional problem is that transfer of transgenes from one line to another requires several generations of backcrossing. However, the past two decades have seen great developments in microbiology. Many new tools and resources are now available that could greatly enhance the biotechnology of the future.

New technologies

Many new and emerging technologies are now available that could transform plant genetic engineering. For example, high throughput sequencing and the wide availability of bioinformatics tools now make identifying target genes and traits easier than ever. Technologies such as site-specific recombination (SSR) and genome editing allow specific regions of the genome to be precisely targeted in order to add or remove genes. Artificial chromosome technology is also part of this emerging group that could be of benefit to plant science. Synthetic chromosomes have already been used in yeast, and widely studied in mammalian systems due to their potential use in gene therapy. Although there have so far been no definitive examples in plants, work has been done in maize that shows the potential of the technology for use in GM crops.

Building an artificial chromosome

A minichromosomes is a small, synthetic chromosome with no genes of its own. It can be programmed to express any desirable DNA sequence that could encode for one, or a number, of genes. An ideal minichromosome would be small and only contain essential elements such as a centromere, telomeres and origin of replication. Once introduced into the plant the minichromosomes should be designed such that interference with host growth and development is minimal. A key requirement is that the chromosome is stable during both meiosis and mitosis. This would ensure introduced genes do not become disrupted or mutated during cell division and reproduction. Gene expression would therefore remain the same for many generations. Finally, the DNA sequence on the minichromosomes could be designed such that it is amenable to SSR or gene editing systems. This would allow re-design and addition of new traits further down the line.

Potential advantages of artificial chromosomes

Plant artificial chromosomes (PACs) have many advantages over traditional transformation systems. For example, to confer complex traits such as disease resistance and tolerance to abiotic stresses such as heat and drought, multiple genes are required. This is not easy with current methods of modification.

PACs could offer a new way to introduce beneficial traits to our crops plants and feed a growing population.Image by Seattle.Romer. Used under Creative Commons 2.0.

However, PACs allow an almost unlimited number of genes to be integrated into the host system. A further possibility that comes from being able to add multiple genes is the addition of new metabolic pathways into the plant. This could allow us to change the nutrients produced by a plant to benefit our diets. Additionally, in a contained environment, plants could be used as a cheap, sustainable way to produce pharmaceuticals. A second major benefit of PACs is that they avoid linkage drag. This is when a desirable gene is closely linked to a deleterious gene that acts to reduce plant fitness. Where this linkage is very tight even repeated backcrossing cannot separate out the genes. Design of new DNA sequences completely avoids this problem, and could allow us to select out detrimental traits from out crop plants.

Regulations for novel biotechnology

Emerging technologies pose new questions to policy makers regarding GM regulation. For example, the use of genome editing, whereby specific sites in the genome are targeted and modified, produces an end product with a phenotype almost identical to one that could be achieved through conventional breeding. This sets genome-edited crops apart from other transgene-containing GM material. For this reason many now argue that genome-edited crops ought not to come under current GM regulations. Much of this argument centres on whether or not to regulate the scientific technique used to produce a crop, or to regulate the end product in the field. For more information on genome editing including current regulations and consensus, see the links at the end of this article.

PACs pose a different set of problems entirely. Minichromosomes would be foreign bodies in the plant, and gene stacking within these introduces even more foreign genes than is possible with current technologies. This would require extensive assessment of both environmental and health effects prior to commercialization. Currently regulatory approval costs around $1-15 million per insertion into the genome. These heavy charges may discourage the further development of minichromosomes technology. However, with PACs it is possible that a particular package of genes could be assessed once, and then transferred into numerous cultivars. This would eliminate the requirement to individually engineer and test every cultivar, so perhaps saving time and money in the long term.

More information on genome editing:

Sense about science genome editing Q & A

The regulatory status of genome-edited crops

The Guardian article on genome editing regulation

A proposed regulatory network for genome edited crops in Nature

A recent workshop on the CRISPR-CAS system of genome editing was held in September 2015 by GARNet and OpenPlant at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, UK. You can read the full meeting report here.