This week’s post was written by Caroline Wood, a PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield.

When it comes to crop diseases, insects, viruses, and fungi may get the media limelight but in certain regions it is actually other plants which are a farmer’s greatest enemy. In sub-Saharan Africa, one weed in particular – Striga hermonthica – is an almost unstoppable scourge and one of the main limiting factors for food security.

Striga is a parasitic plant; it attaches to and feeds off a host plant. For most of us, parasitic plants are simply harmless curiosities. Over 4,000 plants are known to have adopted a parasitic mode of life, including the seasonal favorite mistletoe (a stem parasite of conifers) and Rafflesia arnoldii, nicknamed the “corpse flower” for its huge, smelly blooms. Although the latter produces the world’s largest flower, it has no true roots – only thread-like structures that infect tropical vines.

When parasitic plants infect food crops, they can turn very nasty indeed. Striga hermonthica is particularly notorious because it infects almost every cereal crop, including rice, maize, and sorghum. Striga is a hemiparasite, meaning that it mainly withdraws water from the host (parasitic plants can also be holoparasites, which withdraw both water and carbon sugars from the host). However, Striga also causes a severe stunting effect on the host crop (see Figure 1), reducing their yield to practically nothing. Little wonder then, that the common name for Striga is ‘witchweed’.

Figure 1: Striga-infected sorghum. Note the withered, shrunken appearance of the infected plants. Image credit: Joel Ransom.

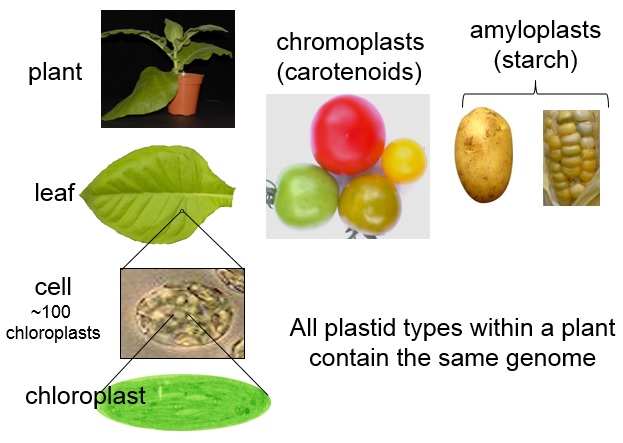

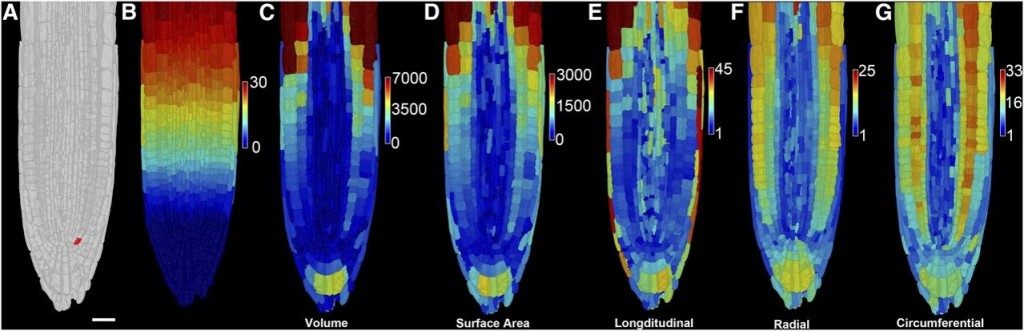

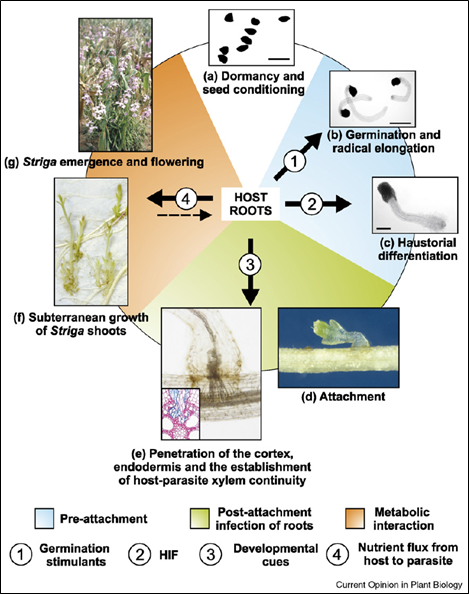

Several features of the Striga lifecycle make it especially difficult to control. The seeds can remain dormant for decades and only germinate in response to signals produced by the host root (called strigolactones) (Figure 2). Once farmland becomes infested with Striga seed, it becomes virtually useless for crop production. Germination and attachment takes place underground, so the farmer can’t tell if the land is infected until the parasite sends up shoots (with ironically beautiful purple flowers). Some chemical treatments can be effective but these remain too expensive for the subsistence farmers who are mostly affected by the weed. Many resort to simply pulling the shoots out as they appear; a time-consuming and labor-intensive process. It is estimated that Striga spp. cause crop losses of around US $10 billion each year [1].

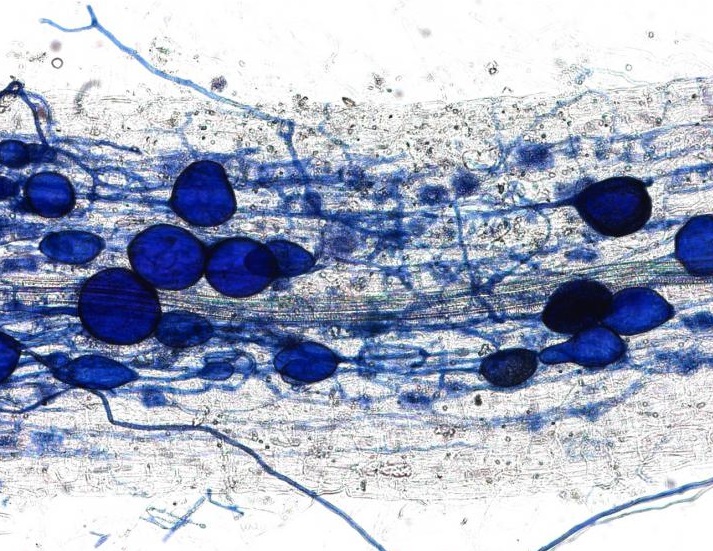

Certain crop cultivars and their wild relatives show natural resistance to Striga. Here at the University of Sheffield, our lab group (headed by Professor Julie Scholes) is working to identify resistance genes in rice and maize, with the eventual aim of breeding these into high-yielding cultivars. To do this, we grow the host plants in rhizotrons (root observation chambers) which allow us to observe the process of Striga attachment and infection (see Figure 3). Already this has been successful in identifying rice cultivars that have broad-spectrum resistance to Striga, and which are now being used by farmers across Africa.

Figure 2: Life cycle of Striga spp. A single plant produces up to 100,000 seeds, which can remain viable in the soil for 20 years. Following a warm, moist conditioning phase, parasite seeds become responsive to chemical cues produced by the roots of suitable hosts, which cause them to germinate and attach to the host root. The parasite then develops a haustorium: an absorptive organ which penetrates the root and connects to the xylem vessels in the host’s vascular system. This fuels the development of the Striga shoots, which eventually emerge above ground and flower. Figure from [2].

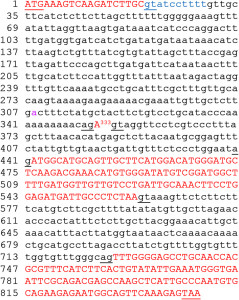

But many fundamental aspects of the infection process remain almost a complete mystery, particularly how the parasite overcomes the host’s intrinsic defense systems. It is possible that Striga deliberately triggers certain host signaling pathways; a strategy used by other root pathogens such as the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. This is the focus of my project: to identify the key defense pathways that determine the level of host resistance to Striga. It would be very difficult to investigate this in crop plants, which typically have incredibly large genomes, so my model organism is Arabidopsis thaliana, the workhorse of the plant science world, whose genome has been fully sequenced and mapped. Arabidopsis cannot be infected by Striga hermonthica but it is susceptible to the related species, Striga gesnerioides, which normally infects cowpea. I am currently working through a range of different Arabidopsis mutants, each affected in a certain defense pathway, to test whether these have an altered resistance to the parasite. Once I have an idea of which plant defense hormones may be involved (such as salicylic acid or jasmonic acid), I plant to test the expression of candidate genes to decipher what is happening at the molecular level.

Figure 3: One of my Arabidopsis plants growing in a rhizotron. Preconditioned Striga seeds were applied to the roots three weeks ago with a paintbrush. Those that successfully attached and infected the host have now developed into haustoria. The number of haustoria indicates the level of resistance in the host. Image credit: Caroline Wood.

It’s early days yet, but I am excited by the prospect of shedding light on how these devastating weeds are so effective in breaking into their hosts. Ultimately this could lead to new ways of ‘priming’ host plants so that they are armed and ready when Striga attacks. It’s an ambitious challenge, and one that will certainly keep me going for the remaining two years of my PhD!

You can follow my journey by reading my blog and keeping up with me on Twitter (@sciencedestiny).

References:

[1] Westwood, J. H. et al. (2010). The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends in Plant Science, 15(4): 227-235. [2] Scholes, J. D. and Press, M. C. (2008). Striga infestation of cereal crops – an unsolved problem in resource limited agriculture. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 11(2): 180-186.