Dr Anil Day, University of Manchester

This week we spoke to Dr. Anil Day, a synthetic biologist at the University of Manchester who has developed an impressive array of tools and techniques to transform chloroplast genomes.

Could you begin by giving our readers a brief overview of synthetic biology?

Synthetic biology involves the application of engineering principles to biological systems. One approach to understanding a biological system is to break it down into smaller parts, which can be used to design new properties. These redesigned pieces can be reassembled into a new system, tested experimentally, and refined in an iterative process. Synthetic biology projects that are underway in our lab include designing plastids such as chloroplasts with new metabolic functions, and in the longer term the design and assembly of synthetic chloroplast genomes.

Why do you use chloroplasts for synthetic biology systems?

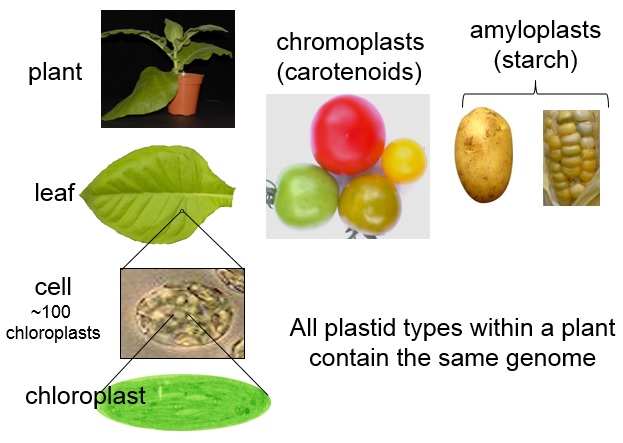

Chloroplasts have a relatively small genome, coding for about 100 genes. Importantly, exogenous (foreign) genes coding for new functions can be precisely introduced into the chloroplast genome. All of the plastids within a plant contain the same genome so, once established, the user-designed reprogrammed plastids will be present throughout the plant. Chloroplasts can also produce very high levels of protein; researchers have achieved expression levels where over 70% of the total soluble protein in the leaves is the engineered protein. Expression in tomato fruit is also possible.

Multiple genes can be introduced into chloroplasts and expressed coordinately, allowing the metabolic engineering of more complex processes. The upper size limit for insertions is not known but is likely to be above the 50,000 nucleotide insertion achieved to date. Furthermore, chloroplasts and other plastids are important metabolic hubs and contain a wide variety of chemical substrates useful for metabolic engineering.

Plants have several types of plastids, including green photosynthetic chloroplasts, pigment-containing chromoplasts, and starch-containing amyloplasts. Credit: Dr. Anil Day.

Could you describe the current state of our ability to engineer chloroplasts?

Chloroplast engineering is routine in many labs around the globe. Although there are multiple chloroplasts in every cell, the process of converting all the chloroplasts to a single population of engineered genomes is not an issue. Most researchers use the tobacco plant because it is easily transformed, but other crops are amenable to transformation, including oilseed rape, soybean, tomato, and potato (cereals such as rice and wheat are more problematic). There has been progress with developing the inducible expression of exogenous genes in chloroplasts too.

What challenges/differences do you face when transforming chloroplast genomes when compared to the nuclear genome?

Typical genetic modification of the DNA in the nucleus is performed by introducing exogenous genes in T-DNA. T-DNA is transferred to the plant using the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which is an efficient process, but the T-DNA integrates ‘randomly’ at many sites within chromosomes and different lines can have variable expression levels due to positional effects and gene silencing.

A. tumefaciens-mediated gene delivery systems do not work for chloroplast transformation. Most chloroplast transformation labs introduce genes into plastids by blasting cells with gold or tungsten particles coated with DNA. Because chloroplast genomes are present in multiple copies per cell, the process of converting all resident chloroplasts to the transgenic genome requires a continued period of selection. This means that the isolation of chloroplast transformants can take slightly longer than nuclear transformation. In our lab, we speed up this process by using restoration of photosynthesis to select chloroplasts with exogenous genes. Once plants with a uniform population of transgenic plastid genomes have been isolated, the transgenes are stable and inherited through the maternal line.

For the novice, I would say nuclear transformation using A. tumefaciens is easier to accomplish than chloroplast transformation.

A tobacco plant containing leaf areas with edited (pale green) and normal (darker green) chloroplasts. Credit: Dr. Anil Day.

Last year you reported that chloroplasts degrade in mature sperm cells just prior to fertilization. Could you elaborate on how this might be utilized in future crop breeding?

Chloroplasts are inherited from the female parent in wheat. This is useful because it restricts the pollen-mediated spread of chloroplast-localized transgenes into the environment. Previously, no-one had studied the mechanism of maternal chloroplast inheritance in wheat using modern cell biology tools. With our collaborators Lucia Primavesi, Huixia Wu, and Huw Jones at Rothamsted Research, we developed an efficient method to observe small non-green plastids in wheat pollen in real time. We found that the plastids were destroyed during the maturation of sperm cells, which explained the absence of paternal plastids in the offspring.

This discovery has applications in crop breeding. Anther culture is a powerful technique where new homozygous plants can be produced by doubling the chromosome numbers of haploid plants regenerated from pollen. This technique has been challenging in cereals, as chloroplast degradation in pollen leads to a high percentage of albino plants (in some cases 100% albinos). Understanding how to prevent the destruction of plastids in pollen sperm cells will improve this technique in cereals, which could speed up crop breeding in the future.

Transformed plantlets are selected by their ability to survive on a herbicide-containing agar plate, and can then be grown up into mature plants. Credit: Dr. Anil Day.

What sorts of processes have you successfully transformed into chloroplasts, and what kinds of results have you achieved?

We have expressed a variety of exogenous genes in chloroplasts, from those conferring resistance to herbicides to vaccine epitopes and pharmaceutical proteins:

- Plants expressing the bar gene in chloroplasts were resistant to the herbicide glufosinate (also known as phosphinothricin).

- A chloroplast-expressed viral epitope was used to identify samples of human blood infected with the hepatitis C virus.

- Human transforming growth factor 3 (hTGFβ3), a potential wound healing drug, accumulated to high concentrations in chloroplasts, and could be processed to a pure active form resembling clinical grade hTGFβ3.

- In collaboration with Ray Dixon, Cheng Qi, and Mandy Dowson-Day at the John Innes Centre, we investigated the feasibility of introducing nitrogen-fixing genes into chloroplasts. This work was initiated in a unicellular green alga with the bacterial nifH gene.

What is the cutting edge of chloroplast transformation research?

Chloroplast genes are important for plant growth and development but they are difficult to improve by conventional breeding methods. We recently developed a method to edit plastid genomes, which allows beneficial single point mutations to be introduced into chloroplast genes. This is important because the resulting plants have an identical genome to the original cultivar apart the single base substitution, potentially leading to a new class of biotech crop.