Coating crop seeds with bacteria found on a desert shrub boosts yields in hot fields.

Bacteria plucked from a desert plant could help crops survive heatwaves and protect the future of food.

Global warming has increased the number of severe heatwaves that wreak havoc on agriculture, reduce crop yields and threaten food supplies. However, not all plants perish in extreme heat. Some have natural heat tolerance, while others acquire heat tolerance after previous exposure to higher temperatures than normal, similar to how vaccines trigger the immune system with a tiny dose of virus.

But breeding heat tolerant crops is laborious and expensive, and slightly warming entire fields is even trickier.

There is growing interest in harnessing microbes to protect plants, and biologists have shown that root-dwelling bacteria can help their herbaceous hosts survive extreme conditions, such as drought, excessive salt or heat.

“Beneficial bacteria could become one of the quickest, cheapest and greenest ways to help achieve sustainable agriculture,” says postdoc Kirti Shekhawat. “However, no long-term studies have proven they work in the real world, and we haven’t yet uncovered what’s happening on a molecular level,” she adds.

To fill this knowledge gap, Shekhawat, along with a team led by Heribert Hirt, selected the beneficial bacteria SA187 that lives in the root of a robust desert shrub, Indigofera argentea. They coated wheat seeds with the bacteria and then planted them in the lab along with some untreated seeds. After six days, they heated the crops at 44 degrees Celsius for two hours. “Any longer would kill them all,” says Shekhawat.

The untreated wheat suffered leaf damage and ceased to grow, while the treated wheat emerged unscathed and flourished, suggesting that the bacteria had triggered heat tolerance. “The bacteria enter the plant as soon as the seeds germinate, and they live happily in symbiosis for the plant’s entire life,” explains Shekhawat.

The researchers then grew their wheat for several years in natural fields in Dubai, where temperatures can reach 45 degrees Celsius. Here, wheat is usually grown only in winter, but the bacteria-bolstered crops consistently had yields between 20 and 50 percent higher than normal. “We were incredibly happy to see that a single bacterial species could protect crops like this,” says Shekhawat.

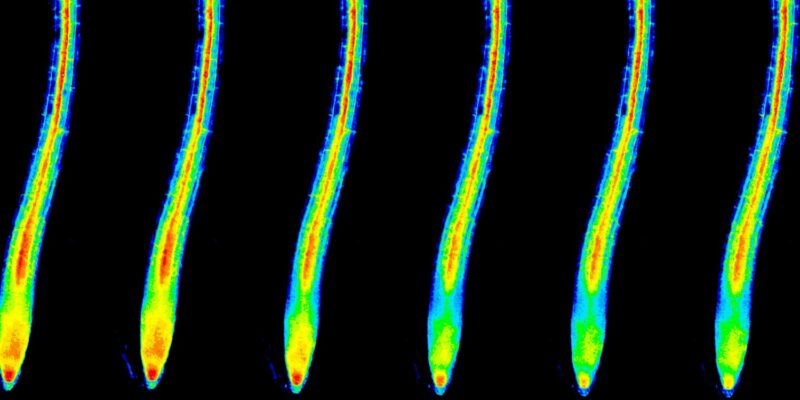

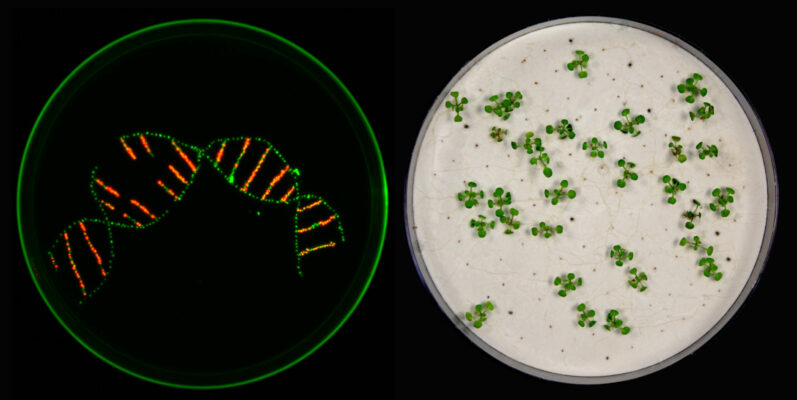

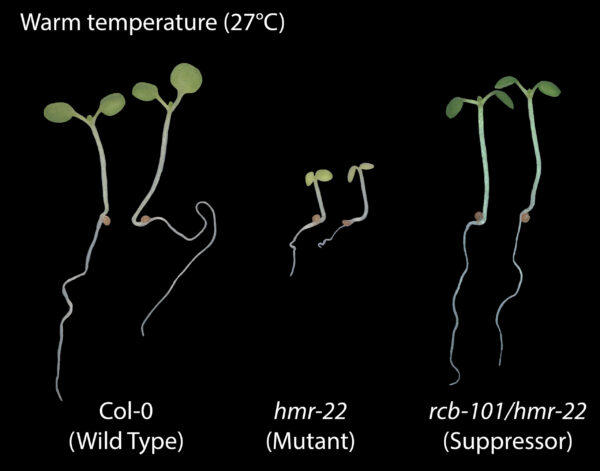

The team then used the model plant Arabidopsis to screen all the plant genes expressed under heat stress, both with and without the bacteria. They found that the bacteria produce metabolites that are converted into the plant hormone ethylene, which primes the plant’s heat-resistance genes for action. “Essentially, the bacteria teach the plant how to use its own defense system,” says Shekhawat.

Thousands of other bacteria have the power to protect plants against diverse threats, from droughts to fungi, and the team is already testing some on other crops, including vegetables. “We have just scratched the surface of this hidden world of soil that we once dismissed as dead matter,” says Hirt. “Beneficial bacteria could help transform an unsustainable agricultural system into a truly ecological one.”

Read the paper: EMBO reports

Article source: KAUST

Image: Studies have shown that root-dwelling bacteria can help plants and crops survive extreme conditions, such as drought, excessive salt or heat. Credit: Anastasia Serin, KAUST