By Atsuko Kanazawa, Igor Houwat, Cynthia Donovan

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

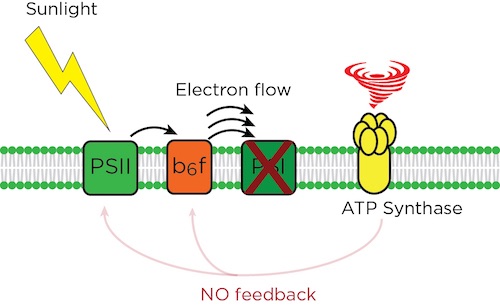

Atsuko Kanazawa is a plant scientist in the lab of David Kramer. Her main focus is on understanding the basics of photosynthesis, the process by which plants capture solar energy to generate our planet’s food supply.

This type of research has implications beyond academia, however, and the Kramer lab is using their knowledge, in addition to new technologies developed in their labs, to help farmers improve land management practices.

One component of the lab’s outreach efforts is its participation in the Legume Innovation Lab (LIL) at Michigan State University, a program which contributes to food security and economic growth in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

Atsuko recently joined a contingent that attended a LIL conference in Burkina Faso to discuss legume management with scientists from West Africa, Central America, Haiti, and the US. The experience was an eye opener, to say the least.

To understand some of the challenges faced by farmers in Africa, take a look at this picture, Atsuko says.

“When we look at corn fields in the Midwest, the corn stalks grow uniformly and are usually about the same height,” Atsuko says. “As you can see in this photo from Burkina Faso, their growth is not even.”

“Soil scientists tell us that much farmland in Africa suffers from poor nutrient content. In fact, farmers sometimes rely on finding a spot of good growth where animals have happened to fertilize the soil.”

Even if local farmers understand their problems, they often find that the appropriate solutions are beyond their reach. For example, items like fertilizer and pesticides are very expensive to buy.

That is where USAID’s Feed the Future and LIL step in, bringing economists, educators, nutritionists, and scientists to work with local universities, institutions, and private organizations towards designing best practices that improve farming and nutrition.

Atsuko says, “LIL works with local populations to select the most suitable crops for local conditions, improve soil quality, and manage pests and diseases in financially and environmentally sustainable ways.”

Unearthing sources of protein

At the Burkina Faso conference, the Kramer lab reported how a team of US and Zambian researchers are mapping bean genes and identifying varieties that can sustainably grow in hot and drought conditions.

The team is relying on a new technology platform, called PhotosynQ, which has been designed and developed in the Kramer labs in Michigan.

PhotosynQ includes a hand-held instrument that can measure plant, soil, water, and environmental parameters. The device is relatively inexpensive and easy to use, which solves accessibility issues for communities with weak purchasing power.

The heart of PhotosynQ, however, is its open-source online platform, where users upload collected data so that it can be collaboratively analyzed among a community of 2400+ researchers, educators, and farmers from over 18 countries. The idea is to solve local problems through global collaboration.

Atsuko notes that the Zambia project’s focus on beans is part of the larger context under which USAID and LIL are functioning.

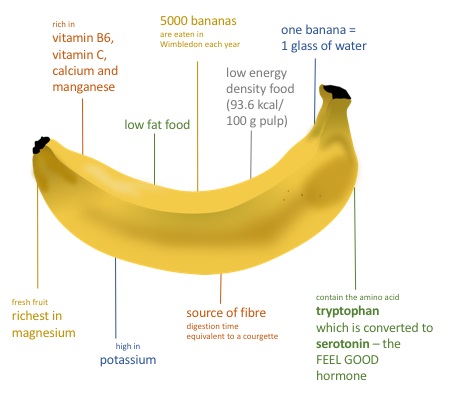

“From what I was told by other scientists, protein availability in diets tends to be a problem in developing countries, and that particularly affects children’s development,” Atsuko says. “Beans are cheaper than meat, and they are a good source of protein. Introducing high quality beans aims to improve nutrition quality.”

Science alone is sometimes not enough

But, as LIL has found, good science and relationships don’t necessarily translate into new crops being embraced by local communities.

Farmers might be reluctant to try a new variety, because they don’t know how well it will perform or if it will cook well or taste good. They also worry that if a new crop is popular, they won’t have ready access to seed quantities that meet demand.

Sometimes, as Atsuko learned at the conference, the issue goes beyond farming or nutrition considerations. In one instance, local West African communities were reluctant to try out a bean variety suggested by LIL and its partners.

The issue was its color.

“One scientist reported that during a recent famine, West African countries imported cowpeas from their neighbors, and those beans had a similar color to the variety LIL was suggesting. So the reluctance was related to a memory from a bad time.”

This particular story does have a happy ending. LIL and the Burkina Faso governmental research agency, INERA, eventually suggested two varieties of cowpeas that were embraced by farmers. Their given names best translate as, “Hope,” and “Money,” perhaps as anticipation of the good life to come.

Another fruitful, perhaps more direct, approach of working with local communities has been supporting women-run cowpea seed and grain farms. These ventures are partnerships between LIL, the national research institute, private institutions, and Burkina Faso’s state and local governments.

Atsuko and other conference attendees visited two of these farms in person. The Women’s Association Yiye in Lago is a particularly impressive success story. Operating since 2009, it now includes 360 associated producing and processing groups, involving 5642 women and 40 men.

“They have been very active,” Atsuko remarks. “You name it: soil management, bean quality management, pest and disease control, and overall economic management, all these have been implemented by this consortium in a methodical fashion.”

“One of the local farm managers told our visiting group that their crop is wonderful, with high yield and good nutrition quality. Children are growing well, and their families can send them to good schools.”

As the numbers indicate, women are the main force behind the success. The reason is that, usually, men don’t do the fieldwork on cowpeas. “But that local farm manager said that now the farm is very successful, men were going to have to work harder and pitch in!”

Back in Michigan, Atsuko is back to the lab bench to continue her photosynthesis research. She still thinks about her Burkina Faso trip, especially how her participation in LIL’s collaborative framework facilitates the work she and her colleagues pursue in West Africa and other parts of the continent.

“We are very lucky to have technologies and knowledge that can be adapted by working with local populations. We ask them to tell us what they need, because they know what the real problems are, and then we jointly try to come up with tailored solutions.”

“It is a successful model, and I feel we are very privileged to be a part of our collaborators’ lives.”

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory