At July’s New Breeding Technologies workshop held in Gothenburg, Sweden, Dr. Staffan Eklöf, Swedish Board of Agriculture, gave us an insight into their analysis of European Union (EU) regulations, which led to their interpretation that some gene-edited plants are not regulated as genetically modified organisms. We speak to him here on the blog to share the story with you.

Could you begin with a brief explanation of your job, and the role of the Competent Authority for GM Plants / Swedish Board of Agriculture?

I am an administrative officer at the Swedish Board of Agriculture (SBA). The SBA is the Swedish Competent authority for most GM plants and ensures that EU regulations and national laws regarding these plants are followed. This includes issuing permits.

You reached a key decision on the regulation of some types of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants. Before we get to that, could you start by explaining what led your team to start working on this issue?

It started when we received questions from two universities about whether they needed to apply for permission to undertake field trials with some plant lines modified using CRISPR/Cas9. The underlying question was whether these plants are included in the gene technology directive or not. According to the Swedish service obligation for authorities, the SBA had to deliver an answer, and thus had to interpret the directive on this point.

Image credit: INRA, Jean Weber. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Could you give a brief overview of Sweden’s analysis of the current EU regulations that led to your interpretation that some CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants are not covered by this legislation?

The following simplification describes our interpretation pretty well; if there is foreign DNA in the plants in question, they are regulated. If not, they are not regulated.

Our interpretation touches on issues such as what is a mutation and what is a hybrid nucleic acid. The first issue is currently under analysis in the European Court of Justice. Other ongoing initiatives in the EU may also change the interpretations we made in the future, as the directive is common for all member states in the EU.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a powerful tool that can result in plants with no trace of transgenic material, so it is impossible to tell whether a particular mutation is natural. How did this influence your interpretation?

We based our interpretation on the legal text. The fact that one cannot tell if a plant without foreign DNA is the progeny of a plant that carried foreign DNA or the result of natural mutation strengthened the position that foreign DNA in previous generations should not be an issue. It is the plant in question that should be the matter for analysis.

Image credit: Frost Museum. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Does your interpretation apply to all plants generated using CRISPR-Cas9, or a subset of them?

It applies to a subset of these gene-edited plants. CRISPR/Cas9 is a tool that can be used in many different ways. Plants carrying foreign DNA are still regulated, according to our interpretation.

What does your interpretation mean for researchers working on CRISPR-Cas9, or farmers who would like to grow gene-edited crops in Sweden?

It is important to note that, with this interpretation, we don’t remove the responsibility of Swedish users to assess whether or not their specific plants are included in the EU directive. We can only tell them how we interpret the directive and what we request from the users in Sweden. Eventually I think there will be EU-wide guidelines on this matter. I should add that our interpretation is also limited to the types of CRISPR-modified plants described in the letters from the two universities.

Will gene-edited crops be grown in Europe in the future? Image credit: Richard Beatson. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

We are currently waiting for the EU to declare whether CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants will be regulated in Europe. Have policymakers in other European countries been in contact with you regarding Sweden’s decision process?

Yes, there is a clear interest; for example, Finland handled a very similar case. Other European colleagues have also shown an interest.

What message would you like plant scientists to take away from this interview? If you could help them to better understand one aspect of policymaking, what would it be?

Our interpretation is just an interpretation and as such, it is limited and can change as a result of what happens; for example, what does not require permission today may do tomorrow. Bear this in mind when planning your research and if you are unsure, it is better to ask. Moreover, even if the SBA (or your country’s equivalent) can’t request any information about the cultivation of plants that are not regulated, it is good to keep us informed.

I think it is vital that legislation meets reality for any subject. It is therefore good that pioneers drive us to deal with difficult questions.

For Africa to end chronic hunger, governments must invest in sustainable water supplies.

The fields are bare under the scorching sun and temperatures rise with every passing week. Any crops the extreme temperatures haven’t destroyed, the insect pests have, and for many farmers, there is nothing they can do. Now, news about hunger across Africa makes mass media headlines daily.

Globally, hunger levels are at their highest. In fact, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, over 70 million people across 45 countries will require food emergency assistance in 2017, with Africa being home to three of the four countries deemed to face a critical risk of famine: Nigeria, South Sudan, Sudan and Yemen. African governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and humanitarian relief agencies, including the United Nations World Food Programme, continue to launch short-term solutions such as food relief supplies to avert the situation. Kenya, for example, is handing cash transfers and food relief to its affected citizens. The UN World Food Programme is also distributing food to drought-stricken Somalia. And in Zambia, the government is employing every tool including its military to combat insect pest infestation.

But why are we here? What happened? Why is there such a large drought?

Many African smallholder farmers depend on rain-fed agriculture, and because last year’s rains were inadequate, many farmers never harvested any crops.

Indeed, failed rains across parts of the Horn of Africa have led to the current drought that is affecting Somalia, south-eastern Ethiopia and northern and eastern Kenya.

Then, even in the countries where adequate rains fell, many of the farmers had to farm on depleted soils, and consequently, the yields were lower. Degraded soils and dependence on rain-fed agriculture coupled with planting the wrong crop varieties are some of the fundamental problems that lead to poor harvests and then to hunger. Worsening the situation is the unpredictable climate. Given these fundamental and basic issues that fuel the hunger cycle in Africa, it naturally makes sense to tackle them.

It is not rocket science. Farming goes hand-in-hand with water. There can be no farming without it. While this seems easy to reason, there are few organisations working to make sure that African farmers and citizens have access to permanent water sources. Access to water sources all year round would ensure that farmers can farm year in and year out.

African governments must, therefore, invest in ensuring that their citizens have access to water. Measures that can be implemented include drilling and rehabilitating boreholes, creating reservoirs and irrigation systems, constructing hand-pumps and implementing water harvesting schemes. Such measures would go a long way and ensure that countries continue to face the same problem both in the short and long term periods.

“If Africa wants to end the recurring droughts, hard decisions must be made.”

Esther Ngumbi, Auburn University in Alabama. United States

Of course it is understandable that it can be hard to choose long-term solutions such as ensuring that citizens have access to permanent water sources year round over investing in short-term solutions when there are people who need help now.

Acknowledging this dilemma, Mitiku Kassa, the Ethiopia’s commissioner for disaster risk management, is reported to have described how hard it was to direct even a fifth of his budget towards well drilling. But such decisions must be made. The Ethiopian government still made that tough decision and sunk hundreds of bore wells throughout the country.

There is a great need to ramp up water harvesting and conservation efforts across the African continent. African governments and other stakeholders need to increase investment in multiple water-storing techniques. Such techniques include rain and flood water harvesting and the construction of water storage ponds and dams. But there should be no need to reinvent the wheel.

African countries can learn from other countries. Countries in the developed world have sustained their agriculture efforts by either drilling water wells to ensure they have access to the water they need for farming or by investing in rain and flood water harvesting. In California, for example, there have been a rise in the number of wells being drilled by farmers who use well water for farming. In 2016 alone, farmers in the San Joaquin Valley dug about 2,500 wells, a number that was five times the annual average reported in the last 30 years.

Countries such as Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand have made progress and are working on pilot projects that capture, harvest and store flood water. Stored water is then available for use by communities when they need it the most. Harvesting and storing water and making it available for agriculture, especially during the dry seasons, will allow citizens and smallholder farmers to farm throughout the year. These would further improve the resilience of farmers to the unpredictability of climate change.

If Africa wants to end the recurring droughts, hard decisions must be made. By addressing the fundamental and basic issues of long-term availability of water for agriculture, African countries can once and for all end this never-ending cycle of hunger.

Esther Ngumbi is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at Auburn University in Alabama, United States. She serves as a 2015 Clinton Global University (CGI U) Mentor for Agriculture and is a 2015 New Voices Fellow at the Aspen Institute.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

Humphrey Nkonde Dramatic threat to maize harvest (Development and Cooperation, 6 March 2017)

Mohammed Yusuf UN: 17 Million People Face Hunger East Africa (Voice of America, 8 March 2017)

Karen McVeigh Somalia famine fears prompt UN call for ‘immediate and massive’ reaction (the Guardian, 3 February 2017)

Emergency food assistance needs unprecedented as Famine threatens four countries (Famine Early Warning Systems Network, 25 January 2017)

Kazungu Samuel Kenya: Red Cross Comes to the Aid of Drought-Hit Kilifi Residents (allAfrica, 2017)

Army worms invades Zambia’s farms (Azania Post, 6 February 2017)

Lesson learned? An urgent call for action in response to the drought crisis in the horn of Africa (Inter Agency Working Group on Disaster Preparedness for East and Central Africa, 2017)

Amanda Little The Ethiopian Guide to Famine Prevention (Bloomberg Business Week, 22 December 2016)

Central Valley farmers drill more, deeper wells as drought limits loom (CBS SF Bay Area, 15 September 2016)

Underground taming floods for irrigation(International Water Management Institute, 2017)

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.

This week’s blog post was written by Dr Damiano Martignago, a genome editing specialist at Rothamsted Research.

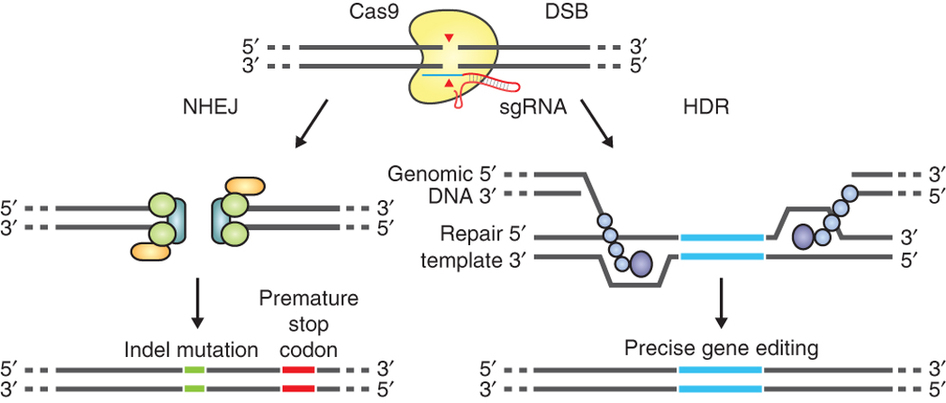

Genome editing technologies comprise a diverse set of molecular tools that allow the targeted modification of a DNA sequence within a genome. Unlike “traditional” breeding, genome editing does not rely on random DNA recombination; instead it allows the precise targeting of specific DNA sequences of interest. Genome editing approaches induce a double strand break (DSB) of the DNA molecule at specific sites, activating the cell’s DNA repair system. This process could be either error-prone, thus used by scientists to deactivate “undesired” genes, or error-free, enabling target DNA sequences to be “re-written” or the insertion of DNA fragments in a specific genomic position.

The most promising among the genome editing technologies, CRISPR/Cas9, was chosen as Science’s 2015 Breakthrough of the Year. Cas9 is an enzyme able to target a specific position of a genome thanks to a small RNA molecule called guide RNA (gRNA). gRNAs are easy to design and can be delivered to cells along with the gene encoding Cas9, or as a pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA protein-RNA complex. Once inside the cell, Cas9 cuts the target DNA sequence homologous to the gRNAs, producing DSBs.

The guide RNA (sgRNA) directs Cas9 to a specific region of the genome, where it induces a double-strand break in the DNA. On the left, the break is repaired by non-homologous-end joining, which can result in insertion/deletion (indel) mutations. On the right, the homologous-directed recombination pathway creates precise changes using a supplied template DNA. Credit: Ran et al. (2013). Nature Protocols.

Together with the increased data availability on crop genomes, genome editing techniques such as CRISPR are allowing scientists to carry out ambitious research on crop plants directly, building on the knowledge obtained during decades of investigation in model plants.

The concept of CRISPR was first tested in crops by generating cultivars that are resistant to herbicides, as this is an easy trait to screen for and identify. One of the first genome-edited crops, a herbicide-resistant oilseed rape produced by Cibus, has already been grown and harvested in the USA in 2015.

Researchers used CRISPR to engineer a wheat variety resistant to powdery mildew (shown here), a major disease of this crop. Image credit: NY State IPM Program. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Using CRISPR, scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences produced a wheat variety resistant to powdery mildew, one of the major diseases in wheat. Similarly, another Chinese research group exploited CRISPR to produce a rice line with enhanced rice blast resistance that will help to reduce the amount of fungicides used in rice farming. CRISPR/Cas9 has also been already applied to maize, tomato, potato, orange, lettuce, soybean and other legumes.

Genome editing could also revolutionize the management of viral plant disease. The CRISPR/Cas9 system was originally discovered in bacteria, where it provided them with molecular immunity against viruses, but it can also be moved into plants. Scientists can transform plants to produce the Cas9 and gRNAs that target viral DNA, reducing virus accumulation; alternatively, they can suppress those plant genes that are hijacked by the virus to mediate its own diffusion in the plants. Since most plants are defenseless against viruses and there are no chemical controls available for plant viruses, the main method to stop the spread of these diseases is still the destruction of the infected plant. For the first time in history, scientists have an effective weapon to fight back against plant viruses.

The cassava brown streak disease virus can destroy cassava crops, threatening the food security of the 300 million people who rely on this crop in Africa. Image credit: Katie Tomlinson (for more on this topic, read her blog here).

Genome editing will be particularly useful in the genetic improvement of many crops that are propagated mainly by vegetative reproduction, and so very difficult to improve by traditional breeding methods involving crossing (e.g. cassava, banana, grape, potato). For example, using TALENs, scientists from Cellectis edited a potato line to minimize the accumulation of reducing sugars that may be converted into acrylamide (a possible carcinogen) during cooking.

One of the hypothesized risks of using CRISPR/Cas9 is the potential targeting of undesired DNA regions, called off-targets. It is possible to limit the potential for off-targets by designing very specific gRNAs, and all of the work published so far either did not detect any off-targets or, if detected, they occurred at a very low frequency. The number of off-target mutations produced by CRISPR/Cas9 is therefore minimal, especially if compared with the widely accepted random mutagenesis of crops used in plant breeding since the 1950s.

Genome editing is interesting from a regulatory point of view too. After obtaining the desired heritable mutation using CRISPR/Cas9, it is possible to remove the CRISPR/Cas9 integrated vectors from the genome using simple genetic segregation, leaving no trace of the genome modification other than the mutation itself. This means that some countries (including the USA, Canada, and Argentina) consider the products of genome editing on a case-by-case basis, ruling that a crop is non-GM when it contains gene combinations that could have been obtained through crossing or random mutation. Many other countries are yet to issue an official statement on CRISPR, however.

Recently, scientists showed that is possible to edit the genome of plants without adding any foreign DNA and without the need for bacteria- or virus-mediated plant transformation. Instead, a pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is delivered to plant cells in vitro, which can edit the desired region of the genome before being rapidly degraded by the plant endogenous proteases and nucleases. This non-GM approach can also reduce the potential of off-target editing, because of the minimal time that the RNP is present inside the cell before being degraded. RNP-based genome editing has been already applied to tobacco plants, rice, and lettuce, as well as very recently to maize.

In conclusion, genome editing techniques, and CRISPR/Cas9 in particular, offers scientists and plant breeders a flexible and relatively easy approach to accelerate breeding practices in a wide variety of crop species, providing another tool that we can use to improve food security in the future.

For more on CRISPR, check out this recent TED Talk from Ellen Jorgensen:

Dr Damiano Martignago is a plant molecular biologist who graduated from Padua University, Italy, with a degree in Food Biotechnology in 2009. He obtained his PhD in Biology at Roma Tre University in 2014. His experience with CRISPR/Cas9 began in the lab of Prof. Fabio Fornara (University of Milan), where he used CRISPR/Cas9 to target photoperiod genes of interest in rice and generate mutants that were not previously available. He recently moved to Rothamsted Research, UK, where he works as Genome Editing Specialist, transferring CRISPR/Cas9 technology to hexaploid bread wheat with the aim of improving the efficiency of genome editing in this crop. He is actively involved with AIRIcerca (International Association of Italian Scientists), disseminating and promoting scientific news.

In June 2016, the UK Government will hold a public referendum for the people to decide whether or not Britain should exit the European Union. This contentious issue, popularly known as “Brexit”, has even divided the governing political party, with key parliamentary figures standing on either side of the debate.

There are many complex political issues for the UK to consider ahead of this referendum. One of these issues is: “what would be the consequences for UK agriculture if Britain were to leave the EU?” Professor Wyn Grant, a member of the Farmer–Scientist Network in the UK, tells us about a new report asking this very question.

by Wyn Grant

The Farmer–Scientist Network was set up by the Yorkshire Agricultural Society (UK) to facilitate practical cooperation between farmers and academics on the challenges facing agriculture. The Network felt there was a need to produce an assessment of the possible consequences of Brexit for agriculture. A working party was established, made up of leading experts on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and farmer members. I chaired this working party, and we produced what we hope is a comprehensive report, available here: http://yas.co.uk/charitable-activities/farmer-scientist-network/brexit.

In producing the Brexit report, one of our objectives was to provide information that farmers and others concerned with agriculture could use to question politicians during the referendum campaign. We also felt that agriculture and food had not been given sufficient attention during the negotiations and subsequent discussions. Should Brexit occur, our report draws attention to the issues that would have to be considered in exit negotiations.

In producing the Brexit report, one of our objectives was to provide information that farmers and others concerned with agriculture could use to question politicians during the referendum campaign. We also felt that agriculture and food had not been given sufficient attention during the negotiations and subsequent discussions. Should Brexit occur, our report draws attention to the issues that would have to be considered in exit negotiations.

When evaluating the implications of Brexit for agriculture, we expected there would be complexities and uncertainties, but these were, in fact, greater than we anticipated. One reason for this is that, although the Lisbon Treaty on which the EU is founded makes provision for Member States to leave the EU under ‘Article 50’, none have ever done so before. It is difficult to know in advance how Britain’s exit would proceed, but it would almost certainly be necessary to use the entire two-year negotiating window provided for in the Treaty. Another complication is that the UK Government has not undertaken any formal contingency planning for exit, so it is difficult to know what a future domestic agricultural policy would look like.

In the event of Brexit taking place, the Farmer–Scientist Network feels that an optimal arrangement for the UK would be to establish a free trade area with the rest of the EU, with tariff-free access for UK farm products to the internal market. However, we don’t think the EU would want to give too generous a deal for fear of encouraging other member states to think about the benefits of exit.

Currently, two ‘pillars’ of financial subsidy are awarded to stakeholders in EU agriculture. We believe that the existing ‘Pillar 1’ subsidies that are given to EU farmers would be vulnerable after Brexit. This is an important issue, as for many farmers these subsidies make the difference between making a profit and running at a loss. Supporters of Brexit argue that the savings made from contributions to the EU budget would more than allow for subsidies to continue to be paid at the existing level. However, this overlooks the fact that the UK Treasury has for a long time targeted these subsidies as “market distorting”, and in the current climate of austerity in the UK, they could be at risk of being phased out as a means to reduce public expenditure.

We did, however, think that the ‘Pillar 2’ subsidies directed at agri-environmental and rural development objectives would be continued in some form. This is in part because they are embedded in contracts that continue beyond 2020, and because they have a coalition of domestic support from outside the industry from environmental and conservation lobbies.

Some farmers resent what they see as excessive regulation emanating from Brussels. However, we think it is unlikely that many of these controls would be dropped or relaxed following Brexit. There are good reasons for regulations covering such areas as water pollution, pesticide use and animal welfare that have nothing to do with membership of the EU. Domestic support for such regulations would continue from environmental, conservation, public health, animal welfare and consumer organisations.

Some farmers hope that plant protection products that have been banned under EU regulations could be used after Brexit. However, there would still be domestic pressure to regulate these products and manufacturers might be unwilling to produce them just for the UK market.

The UK at present negotiates in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) as a part of an EU bloc which provides additional leverage against powerful countries such as the United States. The agreements that the EU has with ‘third’ countries (those outside of Europe) would have to be renegotiated on a single country basis. Supporters of Brexit are confident that this task could be completed within two years. However, given that the UK has relied on the negotiating resources of the European Commission, it does not have many international trade diplomats and the process could take considerably longer.

The horticulture industry in the UK is substantially dependent on migrant labour from elsewhere in the EU. This could not easily be replaced with domestic labour. It would be necessary to try and negotiate a new version of the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) – a scheme (redundant since 2013) that was established to allow migrant workers from certain countries outside of the EU to work in UK agriculture – to ensure that the sector would have the labour it needs to function.

Being part of a larger political community gives British farmers some political cover from countries where farming makes up a large share of GDP or has strong cultural roots. The Farmer–Scientist Network concluded that it was difficult to see Brexit as beneficial to UK agriculture. However, we also emphasised that there are broader considerations about UK membership that needed to be weighed in any voting decision.