This blog has been reposted with permission from the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory.

Unlike animals, plants can’t run away when things get bad. That can be the weather changing or a caterpillar starting to slowly munch on a leaf. Instead, they change themselves inside, using a complex system of hormones, to adapt to challenges.

Now, MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory scientists are connecting two plant defense systems to how these plants do photosynthesis. The study, conducted in the labs of Christoph Benning and Gregg Howe, is in the journal, The Plant Cell.

At the heart of this connection is the chloroplast, the engine of photosynthesis. It specializes in producing compounds that plants survive with. But plants have evolved ways to use it for other, completely unrelated purposes.

Their trick is to harvest their own chloroplasts’ protective membranes, made of lipids, the molecules found in fats and oils. Lipids have many uses, from making up cell boundaries, to being part of plant hormones, to storing energy.

If plants need lipids for some purpose other than serving as membranes, special proteins break down chloroplast membrane lipids. Then, the resulting products go to where they need to be for further processing.

For example, one such protein, breaks down lipids that end up in plant seed oil. Plant seed oil is both a basic food component and a precursor for biodiesel production.

Now, Kun (Kenny) Wang, a former Benning lab grad student, reports two more such chloroplast proteins with different purposes. Their lipid breakdown products help plants turn on their defense system against living pests and other herbivores. In turn, the proteins, PLIP2 and PLIP3, are themselves activated by another defense system against non-living threats.

In a nutshell, the plant plays a version of the popular children’s game, Telephone, with itself. In the real game, players form a line. The first person whispers a message into the ear of the next person in the line, and so on, until the last player announces the message to the entire group.

In plants, defense systems and chloroplasts also pass along chemical messages down a line. Breaking it down:

“The cross-talk between defense systems has a purpose. For example, there is mounting evidence that plants facing drought are more vulnerable to caterpillar attacks,” Kenny says. “One can imagine plants evolving precautionary strategies for varied conditions. And the cross-talk helps plants form a comprehensive defense strategy.”

Kenny adds, “The chloroplast is amazing. We suspect its membrane lipids spur functions other than defense or oil production. That implies more Telephone games leading to different ends we don’t know yet. We have yet to properly examine that area.”

“Those functions could help us better understand plants and engineer them to be more resistant to complex stresses.”

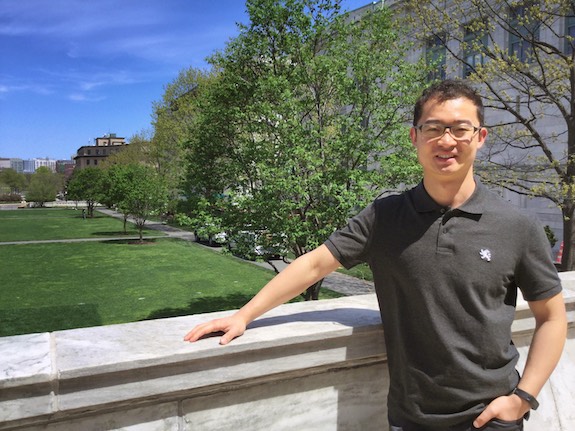

Kenny recently got his PhD from the MSU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. He has just started a post-doc position in the Farese-Walther lab at Harvard Medical School.

“They look at lipid metabolism in mammals and have started a project connecting it with brain disease in humans,” Kenny says. “There is increasing evidence that problems with lipid metabolism in the brain might lead to dementia, Alzheimer’s, etc.”

“I benefited a lot from my time at MSU. The community is very successful here: the people are nice, and you have support from colleagues and facilities. Although we scientists should sometimes be independent in our work, we also need to interact with our communities. No matter how good you are, there is a limit to your impact as an individual. That is one of the lessons I applied when looking for my post-doc.”

Photo of the author, Kun (Kenny) Wang. By Kenny Wang

Read the original article here.

In October 2015, researchers from around the world came together in Iguassu Falls, Brazil, for the Stress Resilience Symposium, organized by the Global Plant Council and the Society for Experimental Biology (SEB), to discuss the current research efforts in developing plants resistant to the changing climate. (See our blog by GPC’s Lisa Martin for more on this meeting!)

Building on the success of the meeting, the Global Plant Council team and attendees compiled a set of papers to provide a powerful call to action for stress resilience scientists around the world to come together to tackle some of the biggest challenges we will face in the future. These four papers were published in the Open Access journal Food and Energy Security alongside an editorial about the Global Plant Council.

In the editorial, the Global Plant Council team (Lisa Martin, Sarah Jose, and Ruth Bastow) introduce readers to the Global Plant Council mission, and describe the Stress Resilience initiative, the meeting, and introduce the papers that came from it.

In the first of the commentaries, Matthew Gilliham (University of Adelaide), Scott Chapman (CSIRO), Lisa Martin, Sarah Jose, and Ruth Bastow discuss ‘The case for evidence-based policy to support stress-resilient cropping systems‘, commenting on the important relationships between research and policy and how each must influence the other.

Global Plant Council President Bill Davies (Lancaster University) and CIMMYT‘s Jean-Marcel Ribaut outline the ways in which research can be translated into locally adapted agricultural best practices in their article, ‘Stress resilience in crop plants: strategic thinking to address local food production problems‘.

In the next paper, ‘Harnessing diversity from ecosystems to crops to genes‘, Vicky Buchanan-Wollaston (University of Warwick), Zoe Wilson (University of Nottingham), François Tardieu (INRA), Jim Beynon (University of Warwick), and Katherine Denby (University of York) describe the challenges that must be overcome to promote effective and efficient international research collaboration to develop new solutions and stress resilience plants to enhance food security in the future.

University of Queensland‘s Andrew Borrell and CIMMYT‘s Matthew Reynolds discuss how best to bring together researchers from different disciplines, highlighting great examples of this in their paper, ‘Integrating islands of knowledge for greater synergy and efficiency in crop research‘.

In all of these papers, the authors suggest practical short- and long-term action steps and highlight ways in which the Global Plant Council could help to bring researchers together to coordinate these changes most effectively.

Read the papers in Food and Energy Security here.

This week we spoke with Dr Sally Howlett, a Knowledge Exchange Fellow with the N8 AgriFood Programme. (More on Sally at the end).

Sally, what is the N8 AgriFood Programme? When and why was it established?

The N8 Research Partnership is a collaboration of the eight most research-intensive universities in the North of England, namely Durham, Lancaster, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Sheffield, and York. It is a not-for-profit organization with the aim of bringing together research, industry and society in joint initiatives. These partners have a strong track record of working together on large-scale, collaborative research projects, one of which is the N8 AgriFood Programme. This £16M multi-disciplinary initiative is funded by the N8 partners and HEFCE (The Higher Education Funding Council for England), and was launched in 2015 to address three key global challenges in Food Security: sustainable food production, resilient food supply chains, and improved nutrition and consumer behavior.

How does plant science research fit into the N8 AgriFood Programme?

There is a strong motivation to ‘think interdisciplinary’ when it comes to developing projects for the N8 AgriFood Programme; therefore, whilst the most obvious home for plant science may be within the theme of sustainable food production, e.g. crop improvement, we see no boundaries when it comes to integrating fundamental research in plant science with applications in all three of our research themes. The testing of research ideas in the ‘real world’ is supported by the five University farms within the N8, which include arable and livestock holdings.

We are launching a Crop Innovation Pipeline to assist with the translation of research into practical applications, with the first event taking place in Newcastle on 2nd-3rd May 2017. It is an opportunity for scientists from academia and industry and representatives from the farming community to discuss their ideas for the implementation of plant biology research into on-farm crop improvement strategies.

How is the work split between the different institutions? How is such a large-scale initiative managed?

Whilst there are many areas of shared expertise between the eight partner institutions, each also has its own areas of specialism within the agri-food arena. The strength of the N8 AgriFood Programme is in working collaboratively to identify complementary strengths and grow those areas in a synergistic way. In this way, we are collectively able to tackle research projects that would not be possible for a single university alone. Pump-priming funds are available at a local and strategic level to support this kick-starting of new multi-institution projects. The Programme itself is led out of the University of York, and each University has its own N8 AgriFood Chair in complementary areas across the Programme. Having both inward- and outward-facing roles, they work with the Knowledge Exchange Fellows and the Programme Lead for each theme to ensure activities at their own institute are connected with what is going on in the wider N8.

What does your work as a Knowledge Exchange Fellow entail?

As a Knowledge Exchange Fellow within the N8 AgriFood Programme, my initial contact with people usually begins with the question ‘What on earth does a Knowledge Exchange Fellow do?’ – and it can be quite difficult to answer! Although some form of knowledge transfer activity has been a defined output of research projects for some time now, knowledge exchange as an ongoing two-way dialogue between researchers and external stakeholders to enable a co-creation process has been less common until recently. Hence dedicated Knowledge Exchange Fellows with academic training are a relatively ‘new’, but growing, phenomenon.

My role is best described as acting as a bridge between the research community and non-academics with a vested interest in developing or using the findings of the research process. It is key to have a good understanding of the perspectives of all parties involved and be able to translate this into the appropriate language for a particular sector. Each of the N8 institutes has appointed Knowledge Exchange Fellow(s), and we work as a cohort to keep abreast of the latest developments in our fields in order to support the development of relationships and innovative projects. In such a huge undertaking, the phrase ‘there is strength in numbers’ is certainly apposite!

How does N8 AgriFood interact with companies?

N8 Agrifood engages with UK-based companies in many ways, including individual face-to-face meetings, attending and hosting networking events, participating in national exhibitions, and holding business-facing conferences. We also run a series of Industry Innovation Forums on various topics throughout the year. These provide a unique opportunity to discuss key challenges, identify problems and deliver new insights into innovation for agri-food, matching practical and technical industry challenges with the best research capabilities of the N8 universities.

How does N8 Agrifood interact with farmers?

As the engine of the agri-food industry, the views and collective experience of the farming community are vitally important in shaping the direction and content of the projects we develop. Co-hosting events with programs such as the ADAS Yield Enhancement Network (YEN), which involves over 100 farms, is one way that we connect with the sector. We are also working with agricultural societies to promote what we are doing and engage directly with their networks of farming members, e.g. the Yorkshire Agricultural Society’s Farmer Scientist Network. Last year we gave a series of seminars at the Great Yorkshire Show and are keen to encourage further collaboration with practicing farmers and growers across the UK.

Does N8 AgriFood collaborate with other research institutes around the world?

The N8 AgriFood Programme has strong international connections and actively welcomes working with international research institutes. Given the interconnectedness of our global food system, we feel that it is vital to link with overseas partners and that real impact can be had by bringing together top researchers from other countries to work together on problems. The value of N8 AgriFood as a one-stop shop is that we represent a large breadth and depth of expertise under a single umbrella, which greatly facilitates collaborating and finding suitable collaboration partners. Our pump-priming funds are a way for researchers to initiate new international partnerships, and we are also working to build links with global research organizations who have shared interests. For example, we recently visited Brazil and China to explore specific opportunities for collaboration and leveraging of research expertise and facilities, and are currently organizing a workshop in Argentina in March.

Where can readers get more information?

If you’d like to find out more, please visit our website: http://n8agrifood.ac.uk/, or consider attending one of our upcoming events:

All images are credited to the N8 Agrifood Programme.

Dr Sally Howlett is a Knowledge Exchange Fellow with the N8 AgriFood Programme. Her research background is in sustainable crop production and plant pest management. After working on the control of invertebrate crop pests in New Zealand for several years, she returned to on-farm research in the UK and extended her focus to include the crops themselves taking a whole-systems view and comparing performance under conventional, organic and agroforestry management approaches. Sally’s role within N8 AgriFood provides a great opportunity to use her experience of agriculture and working with different actors across the sector to engage with external stakeholders, co-producing ideas and multi-disciplinary projects with applications throughout the agrifood chain.

Another fantastic year of discovery is over – read on for our 2016 plant science top picks!

A Zostera marina meadow in the Archipelago Sea, southwest Finland. Image credit: Christoffer Boström (Olsen et al., 2016. Nature).

The year began with the publication of the fascinating eelgrass (Zostera marina) genome by an international team of researchers. This marine monocot descended from land-dwelling ancestors, but went through a dramatic adaptation to life in the ocean, in what the lead author Professor Jeanine Olsen described as, “arguably the most extreme adaptation a terrestrial… species can undergo”.

One of the most interesting revelations was that eelgrass cannot make stomatal pores because it has completely lost the genes responsible for regulating their development. It also ditched genes involved in perceiving UV light, which does not penetrate well through its deep water habitat.

Read the paper in Nature: The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea.

BLOG: You can find out more about the secrets of seagrass in our blog post.

Plants are known to form new organs throughout their lifecycle, but it was not previously clear how they organized their cell development to form the right shapes. In February, researchers in Germany used an exciting new type of high-resolution fluorescence microscope to observe every individual cell in a developing lateral root, following the complex arrangement of their cell division over time.

Using this new four-dimensional cell lineage map of lateral root development in combination with computer modelling, the team revealed that, while the contribution of each cell is not pre-determined, the cells self-organize to regulate the overall development of the root in a predictable manner.

Watch the mesmerizing cell division in lateral root development in the video below, which accompanied the paper:

Read the paper in Current Biology: Rules and self-organizing properties of post-embryonic plant organ cell division patterns.

In March, a Spanish team of researchers revealed how the anti-wilting molecular machinery involved in preserving cell turgor assembles in response to drought. They found that a family of small proteins, the CARs, act in clusters to guide proteins to the cell membrane, in what author Dr. Pedro Luis Rodriguez described as “a kind of landing strip, acting as molecular antennas that call out to other proteins as and when necessary to orchestrate the required cellular response”.

Read the paper in PNAS: Calcium-dependent oligomerization of CAR proteins at cell membrane modulates ABA signaling.

*If you’d like to read more about stress resilience in plants, check out the meeting report from the Stress Resilience Forum run by the GPC in coalition with the Society for Experimental Biology.*

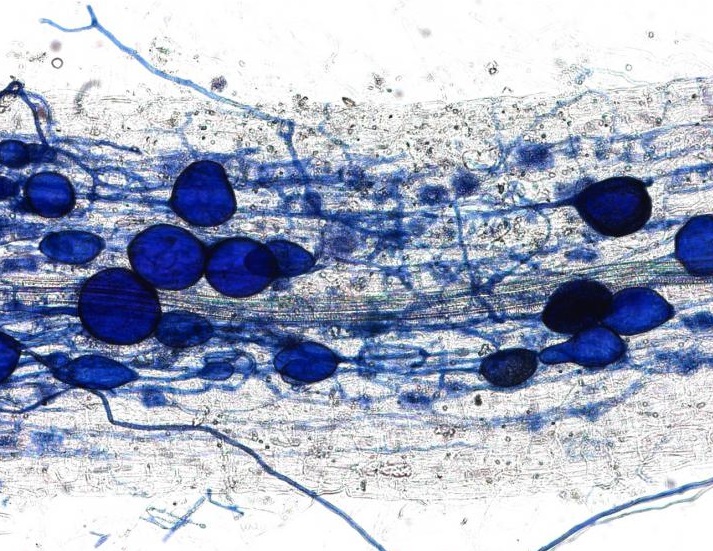

This plant root is infected with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Image credit: University of Zurich.

In April, we received an amazing insight into the ‘decision-making ability’ of plants when a Swiss team discovered that plants can punish mutualist fungi that try to cheat them. In a clever experiment, the researchers provided a plant with two mutualistic partners; a ‘generous’ fungus that provides the plant with a lot of phosphates in return for carbohydrates, and a ‘meaner’ fungus that attempts to reduce the amount of phosphate it ‘pays’. They revealed that the plants can starve the meaner fungus, providing fewer carbohydrates until it pays its phosphate bill.

Author Professor Andres Wiemsken explains: “The plant exploits the competitive situation of the two fungi in a targeted manner, triggering what is essentially a market-based process determined by cost and performance”.

Read the paper in Ecology Letters: Options of partners improve carbon for phosphorus trade in the arbuscular mycorrhizal mutualism.

The transition of ancient plants from water onto land was one of the most important events in our planet’s evolution, but required a massive change in plant biology. Suddenly plants risked drying out, so had to develop new ways to survive drought.

In May, an international team discovered a key gene in moss (Physcomitrella patens) that allows it to tolerate dehydration. This gene, ANR, was an ancient adaptation of an algal gene that allowed the early plants to respond to the drought-signaling hormone ABA. Its evolution is still a mystery, though, as author Dr. Sean Stevenson explains: “What’s interesting is that aquatic algae can’t respond to ABA: the next challenge is to discover how this hormone signaling process arose.”

Read the paper in The Plant Cell: Genetic analysis of Physcomitrella patens identifies ABSCISIC ACID NON-RESPONSIVE, a regulator of ABA responses unique to basal land plants and required for desiccation tolerance.

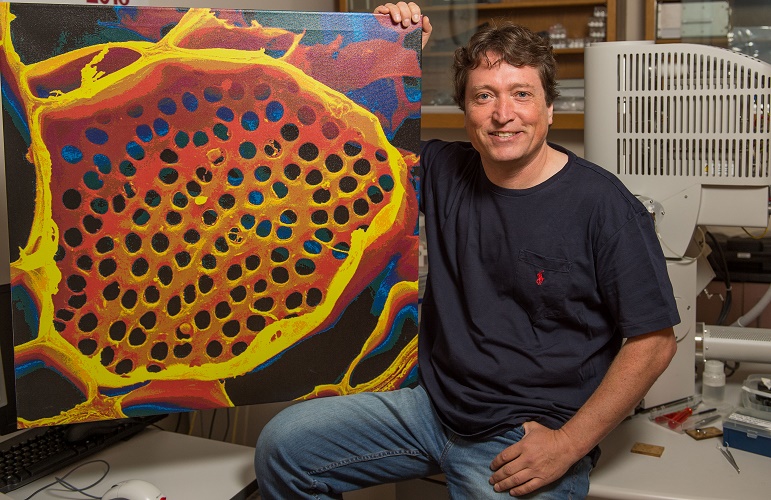

Professor Michael Knoblauch shows off a microscope image of phloem tubes. Image credit: Washington State University.

Sometimes revisiting old ideas can pay off, as a US team revealed in June. In 1930, Ernst Münch hypothesized that transport through the phloem sieve tubes in the plant vascular tissue is driven by pressure gradients, but no-one really knew how this would account for the massive pressure required to move nutrients through something as large as a tree.

Professor Michael Knoblauch and colleagues spent decades devising new methods to investigate pressures and flow within phloem without disrupting the system. He eventually developed a suite of techniques, including a picogauge with the help of his son, Jan, to measure tiny pressure differences in the plants. They found that plants can alter the shape of their phloem vessels to change the pressure within them, allowing them to transport sugars over varying distances, which provided strong support for Münch flow.

Read the paper in eLife: Testing the Münch hypothesis of long distance phloem transport in plants.

BLOG: We featured similar work (including an amazing video of the wound response in sieve tubes) by Knoblauch’s collaborator, Dr. Winfried Peters, on the blog – read it here!

Preserved remains of rope, seeds, reeds and pellets (left), and a desiccated barley grain (right) found at Yoram Cave in the Judean Desert. Credit: Uri Davidovich and Ehud Weiss.

In July, an international and highly multidisciplinary team published the genome of 6,000-year-old barley grains excavated from a cave in Israel, the oldest plant genome reconstructed to date. The grains were visually and genetically very similar to modern barley, showing that this crop was domesticated very early on in our agricultural history. With more analysis ongoing, author Dr. Verena Schünemann predicts that “DNA-analysis of archaeological remains of prehistoric plants will provide us with novel insights into the origin, domestication and spread of crop plants”.

Read the paper in Nature Genetics: Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley.

BLOG: We interviewed Dr. Nils Stein about this fascinating work on the blog – click here to read more!

Another exciting cereal paper was published in August, when an Australian team revealed that C4 photosynthesis occurs in wheat seeds. Like many important crops, wheat leaves perform C3 photosynthesis, which is a less efficient process, so many researchers are attempting to engineer the complex C4 photosynthesis pathway into C3 crops.

This discovery was completely unexpected, as throughout its evolution wheat has been a C3 plant. Author Professor Robert Henry suggested: “One theory is that as [atmospheric] carbon dioxide began to decline, [wheat’s] seeds evolved a C4 pathway to capture more sunlight to convert to energy.”

Read the paper in Scientific Reports: New evidence for grain specific C4 photosynthesis in wheat.

Professor Stefan Jansson cooks up “Tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables”. Image credit: Stefan Jansson.

September marked an historic event. Professor Stefan Jansson cooked up the world’s first CRISPR meal, tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables (genome-edited cabbage). Jansson has paved the way for CRISPR in Europe; while the EU is yet to make a decision about how CRISPR-edited plants will be regulated, Jansson successfully convinced the Swedish Board of Agriculture to rule that plants edited in a manner that could have been achieved by traditional breeding (i.e. the deletion or minor mutation of a gene, but not the insertion of a gene from another species) cannot be treated as a GMO.

Read more in the Umeå University press release: Umeå researcher served a world first (?) CRISPR meal.

BLOG: We interviewed Professor Stefan Jansson about his prominent role in the CRISPR/GM debate earlier in 2016 – check out his post here.

*You may also be interested in the upcoming meeting, ‘New Breeding Technologies in the Plant Sciences’, which will be held at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, on 7-8 July 2017. The workshop has been organized by Professor Jansson, along with the GPC’s Executive Director Ruth Bastow and Professor Barry Pogson (Australian National University/GPC Chair). For more info, click here.*

Phytochromes help plants detect day length by sensing differences in red and far-red light, but a UK-Germany research collaboration revealed that these receptors switch roles at night to become thermometers, helping plants to respond to seasonal changes in temperature.

Dr Philip Wigge explains: “Just as mercury rises in a thermometer, the rate at which phytochromes revert to their inactive state during the night is a direct measure of temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower phytochromes revert to inactivity, so the molecules spend more time in their active, growth-suppressing state. This is why plants are slower to grow in winter”.

Read the paper in Science: Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis.

A fossil ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) leaf with its modern counterpart. Image credit: Gigascience.

In November, a Chinese team published the genome of Ginkgo biloba¸ the oldest extant tree species. Its large (10.6 Gb) genome has previously impeded our understanding of this living fossil, but researchers will now be able to investigate its ~42,000 genes to understand its interesting characteristics, such as resistance to stress and dioecious reproduction, and how it remained almost unchanged in the 270 million years it has existed.

Author Professor Yunpeng Zhao said, “Such a genome fills a major phylogenetic gap of land plants, and provides key genetic resources to address evolutionary questions [such as the] phylogenetic relationships of gymnosperm lineages, [and the] evolution of genome and genes in land plants”.

Read the paper in GigaScience: Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba.

The year ended with another fascinating discovery from a Danish team, who used fluorescent tags and microscopy to confirm the existence of metabolons, clusters of metabolic enzymes that have never been detected in cells before. These metabolons can assemble rapidly in response to a stimulus, working as a metabolic production line to efficiently produce the required compounds. Scientists have been looking for metabolons for 40 years, and this discovery could be crucial for improving our ability to harness the production power of plants.

Read the paper in Science: Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum.

Another amazing year of science! We’re looking forward to seeing what 2017 will bring!

P.S. Check out 2015 Plant Science Round Up to see last year’s top picks!

This week we speak to Tim Williams, the Business Manager of Farming Futures and Research Fund Development Manager at Aberystwyth University, UK.

Could you give a brief introduction to Farming Futures and its mission?

Farming Futures is an independent, UK-based, inclusive agri-food supply chains alliance. Our mission is to work with researchers and industry to share knowledge, with the aim of improving the sustainability and productive efficiency of agriculture, all within the context of healthy, high-quality food.

What is the history of the organization?

Farming Futures started with an idea by Professor Wayne Powell in 2009 (then the director of the Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS) at Aberystwyth) in discussion with Mark Price, who was the Managing Director of British supermarket chain Waitrose. It was launched in 2010, starting out as the Centre of Excellence for UK Farming (CEUKF). Waitrose seed-funded Farming Futures, and since then we have received support from the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) and Innovate UK.

The inauguration meeting of Farming Futures in 2009, then known as the Centre of Excellence for UK Farming. Left-Right: Tim Williams, Wayne Powell, Heather Jenkins, David Davies, Philip Morgan, Jamie Newbold.

How has plant and crop research been integrated into the recommendations presented by Farming Futures?

Plant science is the fundamental driver for agri-food development. We work closely with industry, as well as the AHDB and other farm advisory bodies across the UK to inform them about new developments. Accelerated, directed breeding programs using genomic and phenomic technologies are helping us to develop new varieties that offer more productive, more resilient, environmentally friendly plants – not just as food crops, but also for soil quality, nutrient retention, flood reduction, energy biomass, renewable chemistry, and a host of other desirable characteristics.

Historically, to paraphrase a fellow botanist, we have bred ‘needy, greedy plants’ that deplete resources and need lots of nasty chemicals to keep them growing. Now scientists are mining the genomes of crop ancestors to rediscover the genetic traits we unwittingly threw away on the route to increased yield.

What roles do research partners such as universities play?

We work together in a pre-competitive way to enable research, and to represent farming within agri-food policy – researchers from different organizations can collaborate thanks to our partners’ trusting relationships with each other. Collaborations in science are vital because the problems our global society faces are multi-factorial, non-linear and multi-disciplinary. They are far too complex for the typical university research team, working alone, to address efficiently. We need the equivalent of the CERN Large Hadron Collider project for agri-food.

In addition to helping researchers to bring in millions of pounds worth of applied research projects (at least £12 million, but it is notoriously difficult to find out what industry is funding), Farming Futures helped to establish the government-funded Agri-Food Tech Centres of Innovation for a total of around £90 million, bringing in industry to co-fund and support three of the four: the Agrimetrics Centre, Agri-Epi-Centre and Centre of Innovation Excellence in Livestock. In time, these Centres will catalyze a lot of collaborative research and will help stimulate innovation and technology uptake by industry.

…Economic returns on R&D are about 27 X investment but takes an average of 23 yrs for R&D innovation to be taken up by agriculture. 2/2

— DefraChiefScientist (@DefraChiefScien) January 27, 2016

What climate change challenges will farmers face? Are there any specific challenges that Farming Futures can address?

Farming Futures and its network brings together scientists from different disciplines to discuss these problems and potential solutions. For instance, people from the UK’s national weather service (the Met Office) and some of the biggest food retailers and processors in the world come together at our conferences and workshops to think through scenarios and solutions. These solutions include breeding crops for increased resilience, not just peak yield. We are running out of fungicides that work efficiently, in the same way that we are running out of antibiotics; however, some very clever scientists have worked out some potential solutions that are more environmentally sound, so I am an optimist.

This problem solving is best done at the supply-chain level as it brings in a wider expertise. As I repeat often, a colleague once said to the board of one of the world’s biggest brewers, “No barley = no beer = no business”, inferring the question, “What are you doing to ensure that barley growers are going to be able to supply you in the future?”

Your website has an interesting study from 2011 highlighting six potential jobs of the future, including geoengineer, energy farming, web 3.0 farm host, pharmer, etc. How can students direct their skill development to meet the needs of the future?

There are many emerging jobs and skills, but each of these named jobs from 2011 are actually in practice now. The web 3.0 has now become web 4.0, which is the “internet of things”, with data collection from lots of devices including drones for precision agriculture and robots for weeding and picking crops.

The future of agri-food is in big data, including consumer behavior, weather forecasting, genomics, phenomics, and real-time analysis of the growth progress of plants and animals on-farm. We need more electronic and mechanical engineers with an understanding of biology, as well as more biologists who work within the agri-food industries and in government policy development.

What are you currently working on?

We are currently working with partners on a number of projects across the Agri-Food Tech Centres and trying to form more research collaborations. One of our big projects is The National Library for Agri-Food. I am currently working with web developers and experts from Jisc and the British Library to scope the requirements and to build a demonstration web site.

Finally, I would just like to add that we are open to collaborations across agri-food supply chains and will work to foster them, either openly or privately as appropriate.

In addition to IBERS, Farming Futures has four founding members (Northern Ireland’s Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), Harper Adams University (HAU), NIAB with East Malling Research (NIAB-EMR), and Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC)) and an influential Steering Board, chaired by Lord Curry of Kirkharle, who is very well known and respected in UK government and farming.

The 1000 plants initiative (1KP) is a multidisciplinary consortium aiming to generate large-scale gene sequencing data for over 1000 species of plants. Included in these species are those of interest to agriculture and medicines, as well as green algae, extremophytes and non-flowering plants. The project is funded by several supporters, and has already generated many published papers.

Gane Wong is a Professor in the Faculty of Science at the University of Alberta in Canada. Having previously worked on the Human Genome Project, he now leads the 1KP initiative. Dennis Stevenson, Vice President for Botanical Research, New York Botanical Garden, and Adjunct Professor, Cornell University (USA), studies the evolution and classification of the Cycadales. He became involved in the 1KP initiative as an opportunity to sample the breadth of green plant diversity.

We spoke to both Professor Stevenson (DS) and Professor Wong (GW) about the initiative. Professor Douglas Soltis from Florida Museum of Natural History also contributed to this blog post with input in editing the answers.

What do you think has been the biggest benefit of 1KP?

DS: This has been an unparalleled opportunity to reveal and understand the genes that have led to the plant diversity we see around us. We were able to study plants that were pivotal in terms of plant evolution but which have not previously been included in sequencing projects as they are not considered important economically

The 1KP project presented a fantastic opportunity to explore plant biodiversity. Photo by Bob Leckridge. Used under Creative Commons 2.0.

GW: The project was funded by the Government of Alberta and the investment firm Musea Ventures to raise the profile of the University of Alberta. Notably there was no requirement by the funders to sequence any particular species. I was able to ask the plant science community what the best possible use of these resources would be. The community was in full agreement that the money should be used to sample plant diversity.

Hopefully our work will change the thinking at the funding agencies regarding the value of sequencing biodiversity.

What techniques were utilized in this project to carry out the research?

GW: Complete genomes were too expensive to sequence. Many plants have unusually large genomes and de novo assembly of a polyploid genome remains difficult. To overcome this problem, we sequenced transcriptomes. However, this made our sample collection more difficult as the tissue had to be fresh. In addition, when we started the project, the software to assemble de novo transcriptomes did not work particularly well. I simply made a bet that these problems would be solved by the time we collected the samples and extracted the RNA. For the most part that’s what happened, although we did end up developing our own assembly software as well!

The 1KP initiative is an international consortium. How has the group evolved over time and what benefits have you seen from having this diverse set of skills?

GW: 1KP would not be where it is today without the participation of scientists around the world from many different backgrounds. For example, plant systematists who defined species of interest and provided the tissue samples worked alongside bioinformaticians who analyzed the data, and gene family experts who are now publishing fascinating stories about particular genes.

DS: One of the great things about this project is how it has evolved over time as new researchers became involved. There is no restriction on who can take part, which species can be studied or which questions can be asked of the data. This makes the 1KP initiative unique compared to more traditionally funded projects.

GW: We continually encouraged others to get involved and mine our data for interesting information. We did a lot of this through word of mouth and ended up with some highly interesting, unexpected discoveries. For example, an optogenetics group at MIT and Harvard used our data to develop new tools for mammalian neurosciences. This really highlights the importance of not restricting the species we study to those of known economic importance.

According to ISI outputs from this research, two of the most highly cited papers from 1KP are here and here.

You aimed to investigate a highly diverse array of plants. How many plants of the major phylogenetic groups have now been sequenced, and are you still working on expanding the data set?

DS: A lot of thought went into the species selection. We aimed for proportional representation (by number of species) of the major plant groups. We also aimed to represent the morphological diversity of those groups.

GW: Altogether, we generated 1345 transcriptomes from 1174 plant species.

Has this project lead to any breakthroughs in our understanding of the phylogeny of plants?

DS: This will be the first broad look at what the nuclear genome has to tell us, and the first meaningful comparison of large nuclear and plastid data sets. However, due to rapid evolution plus extinction, many parts of the plant evolutionary tree remain extremely difficult to solve.

Hornworts are non-vascular plants that grow in damp, humid places. Photo by Jason Hollinger. Used under Creative Commons License 2.0.

One significant breakthrough was the discovery of horizontal gene transfer from a hornwort to a group of ferns. This was unexpected and very interesting in terms of the ability of those ferns to be able to accommodate understory habitats.

GW: With regard to horizontal gene transfer, there are papers in the pipeline that will illustrate the discovery of even more of these events in other species. We have also studied gene duplications at the whole genome and gene family level. This is the most comprehensive survey ever undertaken, and people will be surprised at the scale of the discoveries. However, we will be releasing our findings shortly as part of a series and it would be unwise for us to give the story away here! Keep a look out for these!

By Hannes Dempewolf

We at the Global Crop Diversity Trust care about wildlings! No, not the people beyond The Wall, but the wild cousins of our domesticated crops. By collecting, conserving and using wild crop relatives, we hope to be able to adapt agriculture to climate change. This project is funded by the Government of Norway, in partnership with the Millennium Seed Bank at Kew in the UK, and many national and international research institutes around the world.

The first step of this project was to map and analyze the distribution patterns of hundreds of crop wild relatives. Next, we identified global priorities for collecting, and are now providing support to our national partners to collect these wild species and use them in pre-breeding efforts. An example of a crop we have already started pre-breeding is eggplant (aubergine). This crop, important in developing countries, has many wild relatives, which we are using to develop varieties that can better withstand abiotic stresses and variable environments.

More recently we have started a discussion with the crop science community on how best to share our data and information about these species, and genetic resources more generally. This discourse that was at the heart of what has now become the DivSeek Initiative, a Global Plant Council initiative that you can read more about in this GPC blog post by Gurdev Khush.

Why should you care?

Good question. I couldn’t possibly answer it better than Sandy Knapp, one of the Project’s recent reviewers, who speaks in the video below.

One of the great leaders in the field, Jack Harlan, also recognized their immense value: “When the crop you live by is threatened you will turn to any source of relief you can find. In most cases, it is the wild relatives that salvage the situation, and we can point very specifically to several examples in which genes from wild relatives stand between man and starvation or economic ruin.”

Wild rice, Oryza officinalis, is being used to adapt commercial rice cultivars to climate change. Photo credit: IRRI photos, used under Creative Commons License 2.0

Crop wild relatives have indeed been used for many decades to improve crops and their value is well recognized by breeders. This is increasingly true also for abiotic stress tolerances, particularly relevant if we care about adapting our agricultural systems to climate change. One such example is the use of a wild rice (Oryza officinalis) to change the flowering time of the rice cultivar Koshihikari (Oryza sativa) to avoid the hottest part of the day.

Share the care

Fostering the community of those who care about crop wild relatives is an important objective of the project. We make sure that all the germplasm collected by partners is accessible to the global community for research and breeding, within the framework of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (the ‘Plant Treaty’). The project invests into building capacity into collecting: it’s not as simple a process as it may sound. The following shows the training in collection in Uganda:

We also put a heavy emphasis on technology transfer and the development of lasting partnerships in all of the pre-breeding projects we support.

The only way we can safeguard and reap the benefits of the genetic diversity of crop wild relatives over the long term is by supporting a vibrant, committed community. We hope you agree, and encourage you to get in touch via cropwildrelatives@croptrust.org.

To find out more about the Crop Trust and how you can take action to help conserve crop diversity for food security, please visit our webpage. For more information about the Crop Wild Relatives project, please visit www.cwrdiversity.org.

Approaches to biofortification

Biofortification is the improvement of the nutritional value of our crops through both traditional breeding and genetic engineering. Alongside DivSeek and Stress Resilience, biofortification is one of the Global Plant Council’s three main initiatives and will be central to addressing many of the challenges facing world health. However, biofortification doesn’t always involve changing our crops in some way. Often the nutrients we are lacking are present in pre-existing crops. We can biofortify our diets simply by identifying what’s missing and altering our life style accordingly.

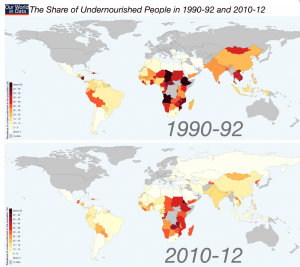

Tackling undernourishment

The share (%) of undernourished people per country. From: Max Roser (2015) -‘Hunger and Undernourishment’. Published online at www.OurWorldInData.org

More often that not we intuitively link biofortification with tackling undernourishment in the developing world, and indeed improvements in the diets of deprived communities would be of enormous benefit to global health.

To do this, a key challenge is to increase the nutrient content of staple food crops such as rice in Asia and maize in sub-Saharan Africa. We need to do this in a sustainable and affordable way; ensuring foods are accessible to those who need it. Alongside the fortification of staple crops we need to identify economical crop species that will grow in harsh environments and provide nutrients currently absent from the diet.

Addressing obesity

It is easy to forget that malnutrition is also a problem in developed countries. Worldwide, at least 2.8 million people per year die from obesity-related illnesses, and in 2011 more than 40 million children under the age of five were overweight. Obesity and related health problems such as diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers, place enormous strain on health services, and are partly a function of poor diet lacking in fibre and key phytonutrients. Addressing this is as important as tackling undernourishment, and many of the same principles apply.

Simple lifestyle changes, such as encouraging the consumption of more fruits and vegetables, are clearly a priority. In addition to this dietary change, if we are going to biofortify foods, there should be an emphasis on crops that are already widely consumed.

Purple tomatoes

Professor Cathie Martin works at the John Innes Centre researching the link between diet and health, and how crops could be fortified to improve our diets and global health.

Tomatoes, are one crop plant already eaten widely in the West, commonly found in fast and convenience foods. For this reason they became the focus of the work of Professor Cathie Martin at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, UK. Cathie’s lab has developed a genetically modified tomato that is rich in anthocyanins, making them purple in colour. Anthocyanins are an important dietary component that can have numerous health benefits, including a potentially significant role in the prevention of diseases such as cancer and diabetes. They are the compounds that give some foods, such as blueberries or eggplant, their distinctive blue or purple colouring. Consuming higher quantities could be highly beneficial to health.

“We focused on anthocyanins because of their huge potential health benefits. Pre-clinical studies show that introducing our purple tomatoes into the diet could be an incredibly effective way to protect against diseases such as cancer. Our next steps will be to confirm these findings in human trials,” says Cathie.

However, naturally occurring tomato varieties containing anthocyanins already exist. Wouldn’t it be better to increase consumption of these rather than creating new ones?

“Indeed purple tomatoes do occur naturally. However, these have anthocyanins only in the skin, in quantities too small to make a significant impact on health. Our genetically modified tomatoes have anthocyanins in all tissues,” explains Cathie.

Since developing the purple tomatoes, Cathie, in collaboration with Professor Jonathan Jones, has set up Norfolk Plant Sciences, the UK’s first GM crop company. However, resistance and uncertainty in Europe surrounding GM technology means that progress has been slow.

“The company was founded in 2007 and we are currently working towards the approval of our purple tomato juice in the USA. Producing just the juice rather than the entire fruit means there are no seeds in the final product. This eliminates environmental challenges without compromising health benefits. If the juice proves successful in the USA we may then work towards approval in the UK and Europe.”

It’s not all about Genetic Modification

Of course if we want to make drastic changes to our foods, such as increase anthocyanins in our tomatoes or carotenoids in our rice, GM technology will be a necessity. However, we can go some way to biofortifying our diets without the use of GM.

Golden rice, shown on the left, is a biofortified crop that accumulates high quantities of provitamin A in the grain. This could help tackle Vitamin A Deficiency in developing countries, from which 500,000 children become blind every year, and nine million will die of malnutrition. Photo credit: IRRI photos used under Creative Commons 2.0

Primarily we really need to focus on changing diet and lifestyle. Promoting plants rich in the nutritional components we need is essential, in addition to encouraging traditional diets such as the Mediterranean diet rich in fish, fruits and vegetables. However, changing people’s behavior and relationship with food is a huge challenge. Cathie cites the UK 5-A-Day governmental campaign as an example.

“This campaign was aimed at encouraging people to eat five portions of fruit or vegetables a day. At the end of this 25-year campaign only 3% more of the UK population was getting their five a day.”

In addition to dietary change, we could biofortify our crops through traditional breeding. For example, one answer to increasing anthocyanins in the diet could be red wheat. Red wheat is rich in anthocyanins, and furthermore less susceptible to pre-harvest sprouting, which causes large crop losses every year for farmers. However, we have so far resisted selecting for this trait in wheat breeding programs as it is not considered esthetically pleasing. To improve our diets we may need to change our expectations of what we want our plates to look like.

Next steps

Plant scientists alone cannot tackle biofortification of our diets! Cathie believes the key to a healthier future is interdisciplinary research:

“Everyone needs to come together: nutritionists, epidemiologists, plant breeders, and plant scientists. However, with such a diverse group of people it is hard to reach agreement on the next steps, and equally as difficult to secure funding for research projects. We really need to promote collaboration and interaction between all groups in order to move forwards.”

The Journal of Experimental Botany (JXB) published a special issue in June entitled ‘Breeding plants to cope with future climate change’

By Jonathan Ingram

The Journal of Experimental Botany (JXB) recently published a special issue entitled ‘Breeding plants to cope with future climate change’.

More often than not, climate change discussions are focused on debating the degree of change we are likely to experience, unpredictable weather scenarios, and politics. However, regardless of the hows and whys, it is now an undeniable fact that the climate will change in some way.

This JXB special issue focuses on the necessary and cutting edge research needed to breed plants that can cope under new conditions, which is essential for continued production of food and resources in the future.

The breadth of research required to address this problem is wide. The 12 reviews included in the issue cover aspects such as research planning and putting together integrated research programs, and more specific topics, such as the use of traditional landraces in breeding programs. Alongside these reviews, original research addresses some of the key questions using novel techniques and methodology. Critically, the research presented comes from a diversity of labs around the world, from European wheat fields to upland rice in Brazil. Taking a global view is essential in our adaptation to climate change.

Avoiding starvation

Why release this special issue now?

Quite simply, the consequences of an inadequate response to climate change are stark for the human population. In fact, as previously discussed on the Global Plant Council blog, changing climate and extreme weather events are already having an impact on food production. For example, drought in Australia (2007), Russia (2010) and South-East China (2013) all resulted in steep increases in food prices. However, a positive side effect of this was to put food security at the top of the global agenda.

A farm in China during drought. Reduced food production can cause steep rises in food prices leading to socio-economic problems.

Photo credit: Bert van Dijk used under Creative Commons License 2.0

Moving forwards, researchers and breeders alike will have to change their fundamental approach to developing novel varieties of crops. In the past, breeders have been highly succesful in increasing yields to feed a growing population. However, we now need to adapt to a rapidly changing and unpredictable environment.

Dr Bryan McKersie sums this up in his contribution to the special issue. He commented: “Current plant breeding methods use large populations and rigorous selection in field environments, but the future environment is different and does not exist yet. Lessons learned from the Green Revolution and development of genetically engineered crops suggest that a new interdisciplinary research plan is needed to achieve food security.”

Driving up yields

So which traits should we be studying to increase resilience to climate change in our crops?

A potentially important characteristic brought to the foreground by Dr Karine Chenu and colleagues (University of Queensland, Australia) is susceptibility to frost damage. Although seemingly counterintuitive at first, the changing climate could result in greater frost exposure at key phases of the crop lifecycle. Warmer temperatures, or clear and cool nights during a drought, would allow vulnerable tissue to emerge earlier in the spring (Gu et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2012). A late frost could then be incredibly destructive to our agricultural systems, causing losses of up to 85% (Paulsen and Heyne, 1983; Boer et al., 1993).

As explained by Dr Chenu, “Finding frost tolerant lines would thus help to deal with frost damage but also with losses due to extreme heat and drought – as they could be avoided by earlier sowings”.

The authors conclude that a “national yield advantage of up to 20% could result from the breeding of frost tolerant lines if useful genetic variation can be found”. The impact of this for future agriculture is incredibly exciting.

This study is just one illustration of the importance of thinking outside the box and investigating a wide range of traits when looking to adapt crops to climate change.

You can find the full Breeding plants to cope with future climate change Special Issue of Journal of Experimental Botany here. Much of the research in the issue is freely available (open access).

Journal of Experimental Botany publishes an exciting mix of research, review and comment on fundamental questions of broad interest in plant science. Regular special issues highlight key areas.

References

Association of Applied Biologists. 2014. Breeding plants to cope with future climate change. Newsletter of the Association of Applied Biologists 81, Spring/Summer 2014.

Boer R, Campbell LC, Fletcher DJ. 1993. Characteristics of frost in a major wheat-growing region of Australia. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 44, 1731–1743.

Gu L, Hanson PJ, Post WM et al. 2008. The 2007 Eastern US spring freeze: increased cold damage in a warming world? BioScience 58, 253–262.

Paulsen GM, Heyne EG. 1983. Grain production of winter wheat after spring freeze injury. Agronomy Journal 75, 705–707.

Zheng BY, Chenu K, Dreccer MF, Chapman SC. 2012. Breeding for the future: what are the potential impacts of future frost and heat events on sowing and flowering time requirements for Australian bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) varieties? Global Change Biology 18, 2899–2914.