A group of scientists from Sechenov University, Russia, and La Trobe University, Australia, have developed a fast and cost-effective method of detecting and identifying bioactive compounds in complex samples such as plant extracts. They successfully applied the method to examine Mediterranean and Australian native culinary herbs. Three articles on this work were published in Applied Sciences, Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis and Journal of Chromatography A.

Since ancient times, people have been using herbs as food additives and medicines, though a search for useful compounds and a study of their properties remain a difficult task. It is possible to examine a compound if it is stable enough and can be separated from other substances in a sample. However, plant extracts contain hundreds of compounds. In the past, only known compounds were investigated by target analysis and most bioactive compounds were left undiscovered. Thus, the number of compounds that are yet to be explored is so huge that methods that can both screen mixtures and identify the compounds responsible for bioactivity are of greater value.

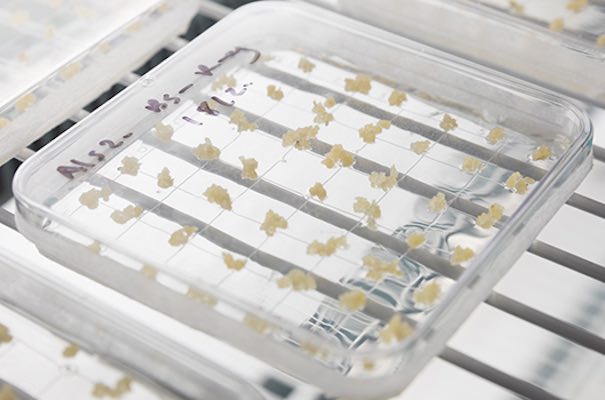

The authors of the papers used an Effect Directed Analysis (EDA) approach, which is a combination of chromatographic separation with in situ (bio)assays and physico-chemical characterisation to discover and identify bioactive compounds in complex plant samples. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and high performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) are well established, chromatographic separation techniques ideally suited for high-throughput screening of bioactive compounds in crude samples.

To separate substances, TLC uses the fact that various compounds are transported by a solvent and absorbed by a sorbent at different speeds. A sorbent-coated plate with a studied mixture is immersed with one end in the solvent, and under the action of capillary forces, it begins to rise along the plate, taking the substances of the mixture with it. As they move upward, the compounds are absorbed by the sorbent and remain as horizontal bands that can be distinguished in visible, infrared or ultraviolet light. Using this method, crude extracts can be analysed directly with no preparation and possible loss of sample components.

Bioassays allow to determine the properties of compounds, such as toxicity, observing how model organisms (bacteria, plants or small animals) react to them. In this way, one can select extracts able to inhibit the action of individual enzymes or reactive oxygen species.

Combination of TLC chromatography with microbial (bacteria and yeast) tests and biochemical (enzyme) bioassays enables rapid and reliable characterization of bioactive compounds directly on the chromatographic plates, without isolation/extraction. The advantage of HPTLC is that plates/chromatograms can be directly immersed into enzyme solution (bioassays), incubated for up to several hours, followed by visualization of the (bio)activity profile via an enzyme substrate reaction as bioactivity zones. This approach is more cost effective, enabling a more streamlined method to detect and characterise natural products that are suitable candidates for further investigation as potential new drug molecules.

Using this method, scientists examined the properties of bioactive compounds from culinary herbs commonly used in the Mediterranean diet: basil, lavender, rosemary, oregano, sage and thyme. Australia’s native plants were added to the list: lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora), native thyme (Prostanthera incisa), sea parsley (Apium prostratum), seablite (Suaeda australis) and saltbush (Atriplex cinerea). Some of the secondary metabolites from these plants exhibit significant antioxidant activity and enzyme inhibition, like α-amylase inhibition. Therefore, these herbs may be preventive not only against cardiovascular diseases but also type 2 diabetes. The enzyme α-amylase breaks down polysaccharides, thereby increasing blood sugar levels. Recent studies suggest that hyperglycemia induces generation of reactive oxygen species, alteration of endogenous antioxidants and oxidative stress. It was found that patients with uncontrolled sugar levels in addition to diabetes also suffer from accelerated cognitive decline independent of their age. Although Australian native herbs are used as a substitute for related European plants, their medicinal properties are much less studied.

After preparing the extracts, the scientists began to study their composition and qualities. Rosemary and oregano extracts showed the greatest antioxidant activity, while sage, oregano and thyme were the best at slowing down reactions involving α-amylase (extracts from lavender flowers and leaves were the only ones not to show this effect). Among the studied Australian native herbs, lemon myrtle showed the strongest antioxidant properties, with the best α-amylase inhibition observed with extracts of native thyme (this property was noticed for the first time), sea parsley and saltbush.

The study of plant extracts using bioassay and thin-layer chromatography allows scientists to examine a variety of compounds, find mixtures that have the desired properties and isolate substances that exhibit them to the greatest extent. This fast and cost-effective method will be useful for finding new drug compounds.

Read the papers: Applied Sciences, Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis and Journal of Chromatography A.

Article source: Sechenov University via Eurekalert

Image credit: Melburnian / Wikimedia

Smart thermostats tell air conditioners to switch on when the sun is bearing down in the summer and when to shut down to conserve energy. Similarly, plants have Rubisco activase, or Rca for short, that tells the plant’s energy-producing enzyme (Rubisco) to kick on when the sun is shining and signals it to stop when the leaf is deprived of light to conserve energy.

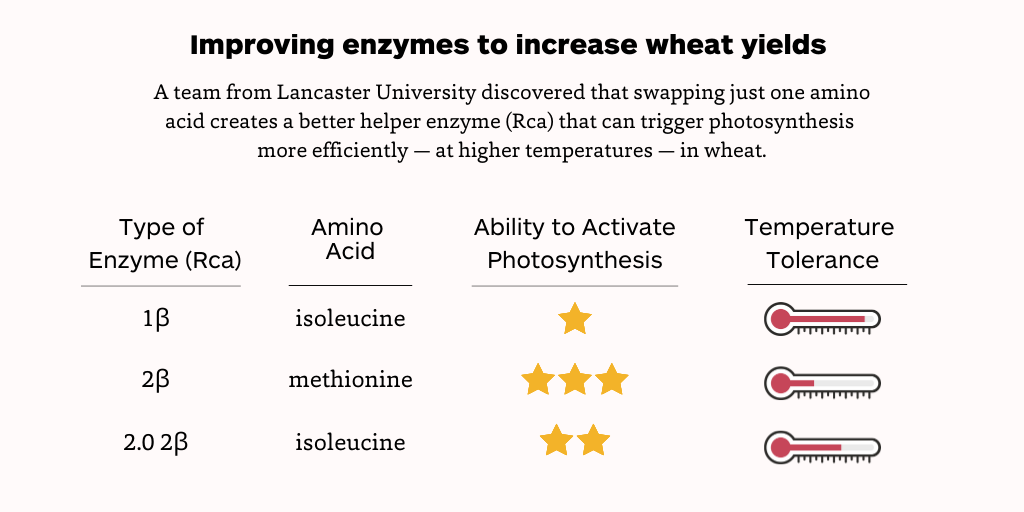

A team from Lancaster University reports in The Plant Journal that swapping just one molecular building block out of 380 that make up an Rca in wheat enables it to activate Rubisco faster in hotter temperatures, suggesting an opportunity to help protect crops from rising temperatures.

“We took a wheat Rca (2β) that was already pretty good at activating Rubisco in lower temperatures and swapped out just one of its amino acids with one found in another wheat Rca (1β) that works pretty well in higher temperatures but is rubbish at activating Rubisco — and the result is a new form of 2β Rca that is the best of both worlds,” said Dr Elizabete Carmo-Silva, a senior lecturer at the Lancaster Environment Centre who oversaw this work for a research project called Realizing Increased Photosynthetic Efficiency (RIPE).

RIPE is engineering crops to be more productive by improving photosynthesis, the natural process all plants use to convert sunlight into energy and yields. RIPE is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.S. Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), and the U.K. Government’s Department for International Development(DFID).

Here’s the breakdown: naturally occurring wheat Rca 1β has an isoleucine amino acid, works up to 39 degrees Celcius, but isn’t great at activating Rubisco, whereas the naturally occurring 2β has a methionine amino acid, works up to about 30 degrees Celcius, and is good at activating Rubisco. Here the team has created a new version of 2β with an isoleucine amino acid that works up to 35 degrees Celcius and is quite good at activating Rubisco.

“Essentially, 1β is a rubbish enzyme and 2β is sensitive to higher temperatures,” Dr Carmo-Silva said. “The cool thing here is that we have shown how this one amino acid swap can make Rca active at higher temperatures without really affecting its efficiency to activate Rubisco, which could help crops kickstart photosynthesis under temperature stress to churn out higher yields.”

This work was carried out in vitro in E. coli, supported by a Ph.D. studentship by the Lancaster Environment Centre to first author Gustaf Degen. Importantly, these findings will support RIPE’s efforts to characterise and improve the Rca of other food crops such as cowpea and soybean, each with multiple different forms of Rca.

“When looking at cowpea growing regions in Africa, it goes all the way from South Africa with an average around 22 degrees Celcius to Nigeria at about 30, and areas further north get to 38,” Dr Carmo-Silva said. “If we can help Rubisco activate more efficiently across these temperatures, that is really powerful and could help us close the gap between yield potential and the reality for farmers who depend on these crops for their sustenance and livelihoods.”

The RIPE project and its sponsors are committed to ensuring Global Access and making the project’s technologies available to the farmers who need them the most.

Realizing Increased Photosynthetic Efficiency (RIPE) aims to improve photosynthesis to equip farmers worldwide with higher-yielding crops to ensure everyone has enough food to lead a healthy, productive life. This international research project is sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.S. Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, and the U.K. Government’s Department for International Development.

RIPE is led by the University of Illinois in partnership with The Australian National University, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Lancaster University, Louisiana State University, University of California, Berkeley, University of Cambridge, University of Essex, and U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service.

Read the paper: The Plant Journal

Article source: Lancaster University

Image credit: RIPE project