This article is reposted from the Devex blog with kind permission from the author, Lisa Cornish.

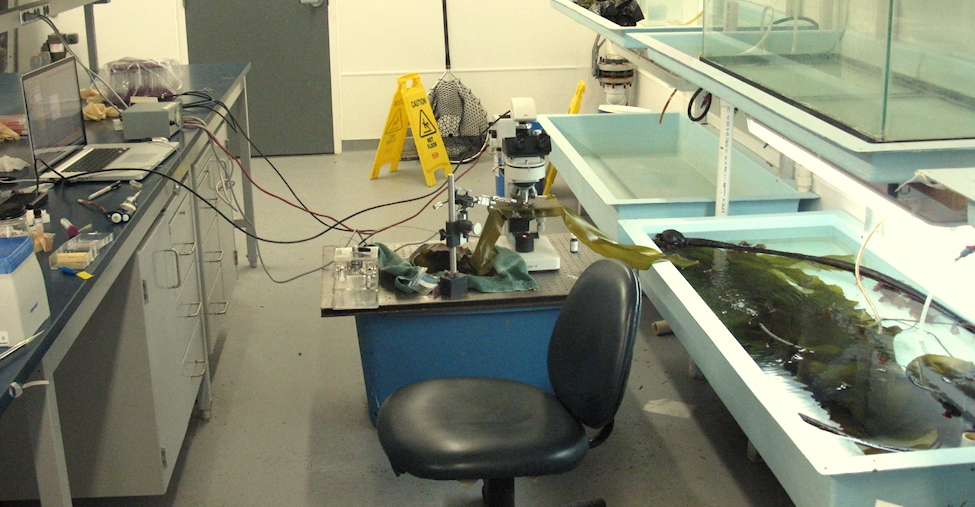

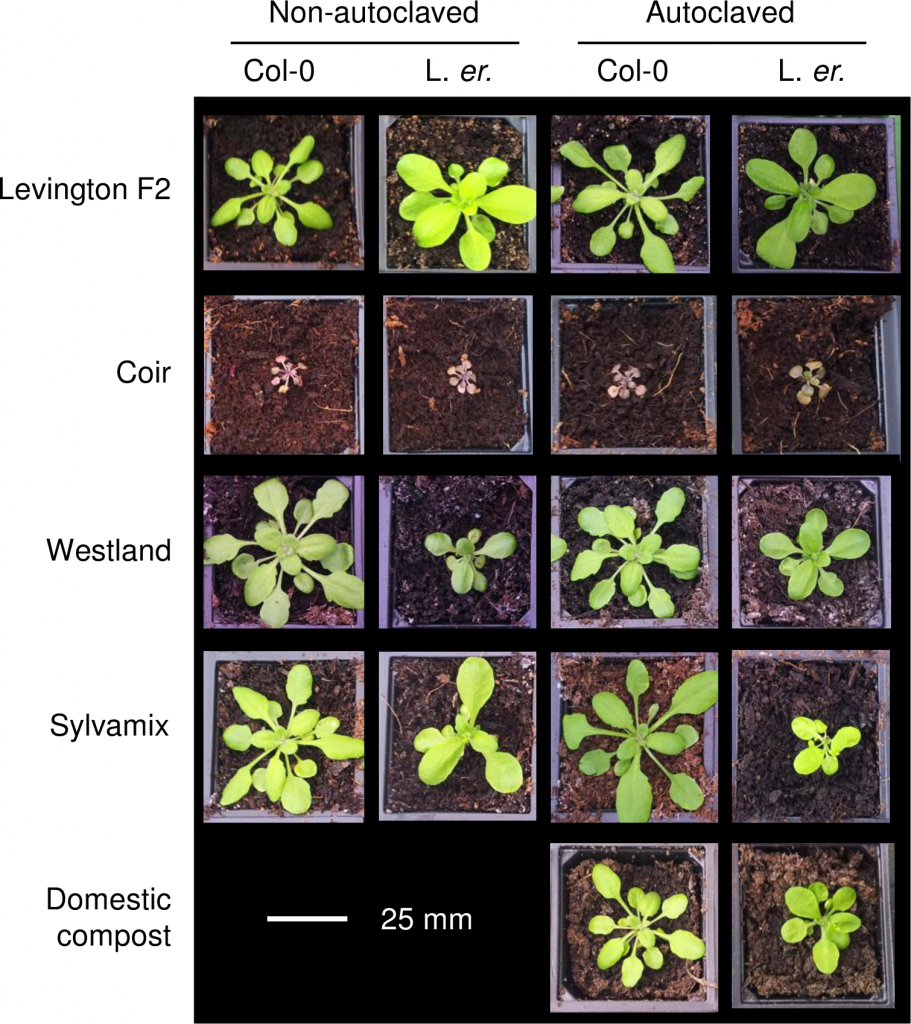

Plant samples in the genebank at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture’s Genetic Resources Unit, at the institution’s headquarters in Colombia. Credit: Neil Palmer / CIAT. Used under license: CC BY-SA 2.0.

It was too dry in the Australian region of Wimmera to produce crops last summer. This year, floods are set to wipe out yields again. Like a number of other regions across the planet, climate change is starting to be felt.

“It’s like this every year somewhere,” said Sally Norton, head of the Australian Grains Genebank, which stores diverse genetic material for plant breeding and research.

For Norton and many of her colleagues in agricultural genetics, the picture is increasingly clear: The variety of crops used today are not able to withstand the changing conditions and changes expected in the future.

Australia’s biodiversity may offer some help, according to discussions at the recent International Genebank Managers Annual General Meeting held in Horsham, Victoria. The gathering, which brings together 11 countries, focused on how to better conserve seeds, build databases to manage collections, boost capacity across the world and fill gaps in genebanks.

Researchers are particularly interested in crop wilds, “the ancestors of our domesticated crops,” Marie Haga, executive director of the The Crop Trust, explained to Devex. Australia is one of the richest sources of these seeds. “It’s like the wolf being the ancestor to our domesticated dogs. Crop wild relatives have traits that we have lost in the domestication process — they might need less water, might live in unfriendly conditions, may be resistant to pests and diseases.”

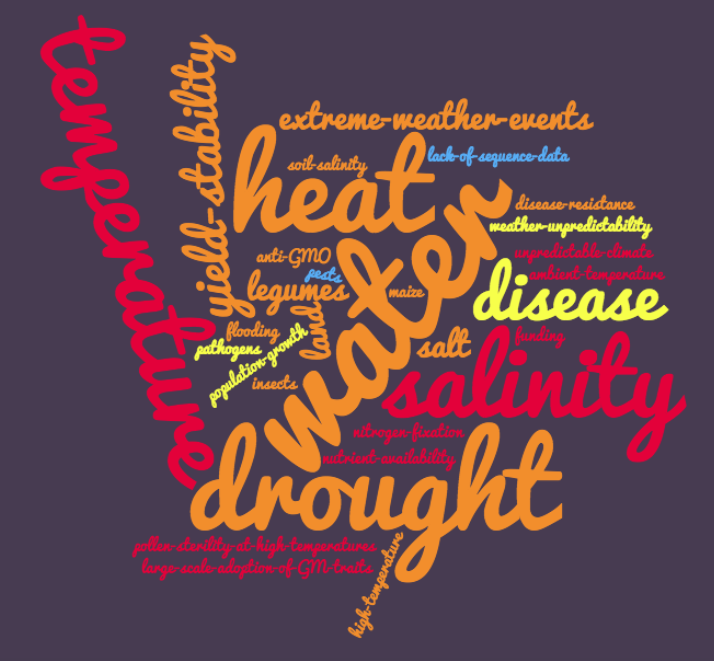

As climate change continues to batter agricultural yields, crop wild relatives could provide resilience. The seeds give breeders and farmers new options of plant varieties with traits to withstand a variety of conditions based on the harsh climates they are found — drought, fire, flood, poor soil, high salinity.

For Haga, crop wild relatives are a solution for food security. “The challenge is that many of the varieties widely used in modern agriculture are very vulnerable, because we have been breeding on the same line and they are adapted to very specific environment,” Haga said. Varieties that flourish today, she said, could wither as the climate fluctuates.

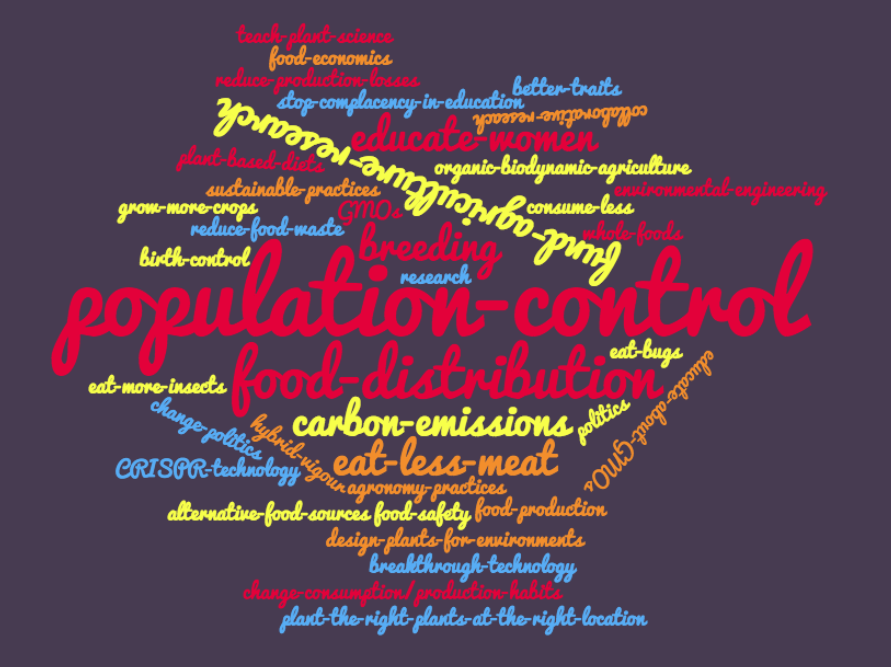

“Utilization of the natural diversity of crops is key to the future,” she said. “The climate is rapidly changing and we need to feed a growing population with more nutritious food. It is very hard to see how we can do this unless we go back to the building blocks of agriculture.”

Norton agreed: “Crop wild relatives have an amazing adaptability to changing conditions,” she told Devex. “When we talk about food security, we are talking about getting varieties in farm paddocks that have greater resilience to extreme conditions. It may not be the highest yield, but you are going to get something from this crop.”

Why have they been overlooked?

Crop wild relatives have so far been underutilized in the research and breeding process of crops.

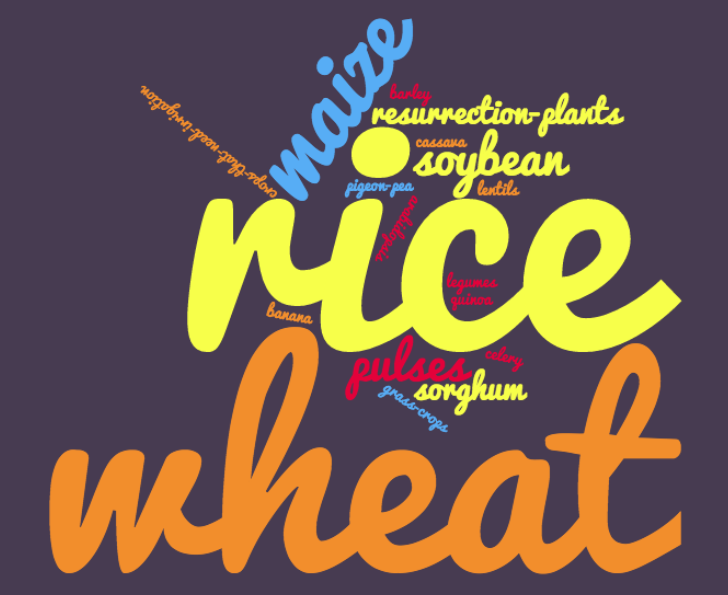

“We have this fabulous natural diversity out there including 125,000 varieties of wheat and 200,000 varieties of rice.” Haga said. “We have not at all unlocked the potential of these crops.”

One reason is a dearth of research. “Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Collecting, Protecting and Preparing Crop Wild Relatives,” a 10-year project led by Haga to ensure long-term conservation of crop wild relatives, conducted a global survey of distribution and conservation and found that of 1,076 known wild relatives for 81 crops, more than 95 percent are insufficiently represented in genebanks and 29 percent are completely missing. They are missing purely due to the fact that they have yet to be collected.

“Genebank managers are generally open to include crop wild relatives in their collections.” Haga said. “It’s just quite simply that not enough work has been done in this area and the full potential is yet to be realized,” she said.

At the moment, seeds are being collected in 25 countries around the world as part of the crop wild relative project, but it is Australia that has been identified as one of the richest sources for crop wild relatives in the world. Because of the continent’s low population density and vast, undisturbed natural environment, a wide variety of species have been conserved, said Norton.

Australia holds significant diversity of wild relatives of rice, sorghum, pigeon pea, banana, sweet potato and eggplant currently missing from global collections, according to research by the Australian Seed Bank Partnership. Forty species have been prioritized for collection with high hopes that they will enable crops to withstand the harsh environmental conditions in which Australian species are found.

There are still many areas of Australia yet to be surveyed, and the full extent of its agricultural riches may yet to be tapped.

Australian researchers will play an important role in pre-breeding local species of wild relatives to improve their use in breeding programs. Crop wild relatives have historically been used in a variety of crops including synthetic wheat, but Australian native wild relatives have been harder to include in the breeding process.

“In the next 10 to 15 years it would be surprising if there is not something coming out that hasn’t got a component of Australian native wild relative in it,” Norton said who is currently involved in the collection of Australian crop wild relatives.

Collection of crop wild relatives is time sensitive

There is an urgency to collect crop wild relatives. Not only are wild species needed now to support changing environmental conditions affecting crops and farming, urbanization is putting crop wild relatives at risk of disappearing.

“We need to collect these sooner rather than later,” Norton told Devex. “Urbanization has a big impact on any native environment, let alone crop wild relatives. We know what species on our target list are more threatened than others — urbanization, flooding and fire are all risks to their security. We certainly have a priority list of species to collect and we need to make sure we target the ones that are under threat first.”

Once the varieties are conserved, breeders and farmers will need to be convinced to start using crop wild relatives. Many are already on board. “Most breeders understand these wild relatives have great potential,” Haga said.

Still, wild relatives can be difficult to work with and produce a lower yield. Haga expects there to be some reluctance, though limited.

“The understanding of the need is increasing and we feel very confident that this material will be used and some of them may be the game changer we are looking for,” she said.

The plans for crop wild relatives

Haga’s 10-year project on crop wild relatives is halfway complete. They are nearing the end of the collection phase and entering the pre-breeding process, before they are able to breed and deliver new species to farmers.

Australian support for the program includes an agreement for additional amount of $5 million. That comes on top of previous support of $21.2 million to the Crop Diversity Endowment Fund, which supports crop diversity globally and with a focus on the Indo-Pacific. Brazil, Chile, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the United States are among other supporters of the endowment fund that hopes to reach $850 million. In Australia, further resources are still required to fund and support better seed collection at home.

Globally, plans for crop wild relatives includes raising greater awareness of their potential and importance.

“We have a big job to do to create awareness of the important of crop diversity generally and crop wild relatives specifically,” Haga said. “We have been speaking for years about biodiversity in birds and fish and a range of other animals, but we have talked very little about conserving the diversity of crops. I will fight for all types of diversity, but especially plants.”

This article is reposted from the Devex blog with kind permission from the author, Lisa Cornish.