In recent years, foresters have been able to observe it up close: First, prolonged drought weakens the trees, then bark beetles and other pests attack. While healthy trees keep the invaders away with resin, stressed ones are virtually defenseless. Freiburg scientist Sylvie Berthelot and her team of researchers from the Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources and the Faculty of Biology are studying the importance of tree diversity on bark beetle infestation. They are investigating whether the composition of tree species affects bark beetle feeding behavior. The team recently published their findings in the Journal of Ecology.

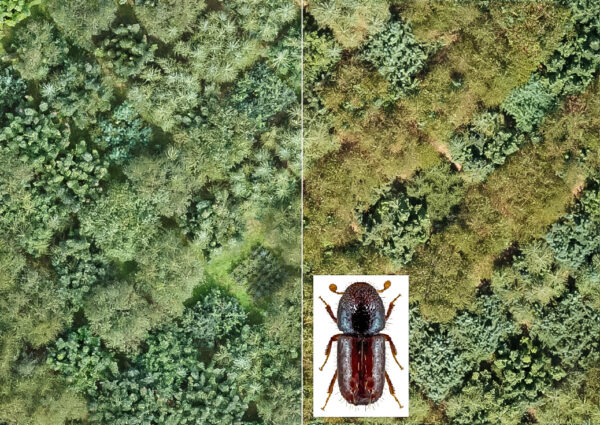

In a 1.1 hectare experimental set-up in Freiburg, six native deciduous and coniferous tree species from Europe and six deciduous and coniferous tree species from North America were each planted in different mono- and mixed plots. After the severe drought in the summer of 2018, the Sixtoothed spruce bark beetle mainly attacked the native species: the European spruce and the European larch. “We were surprised that the beetles exhibited only a slight interest in the exotic conifer species, such as the American spruce,” Berthelot says.

While measuring the infestation, the researchers found that the position within the experimental site was also crucial. The trees at the edge were attacked the most. Therefore, Berthelot suspects that the bark beetle entered the testing plot from outside. “In addition, environmental influences weaken the unprotected outer trees more, so they are more susceptible.”

At the same time, the likelihood of which trees the bark beetles will attack changes the more tree species there are. Until now, the researchers assumed that tree diversity reduces the infestation of insect pests such as the bark beetle. But their experiment shows that “increasing tree diversity can reduce the risk of bark beetle infestation for species that are susceptible to high infestation rates, such as larch and spruce. But the risk for less preferred species such as pine or exotic trees may increase with tree diversity, as beetles, once attracted, also attack these trees,” Berthelot says. Although the study indicates that non-native tree species are less attacked because the bark beetles are unfamiliar with these species. “However, this effect may weaken over the years,” she said. As a result, the risk of infestation in mixed forests is redistributed among tree species rather than reduced for all.

Read the paper: Journal of Ecology

Article source: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg

Image: Aerial view of the IDENT tree diversity experiment near Freiburg before (left) and after (right) the 2018 drought and bark beetle infestation. Credit: aerial photos by K. R. Kovach, Sixtoothed spruce bark beetle photo by U. Schmidt.