Passion fruit woodiness caused by cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus (CABMV), the disease that most affects passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) grown in Brazil, can be combated with a relatively simple technique.

A study published in the journal Plant Pathology shows that systematic eradication of plants with symptoms of the disease preserves the crop as a whole and keeps plants producing for at least 25 months.

The technique currently used to combat CABMV entails renewing the entire orchard every year. This is, of course, a costly procedure. According to the authors of the study, economic factors are critical for this crop, which is mostly grown by small producers.

CABMV occurs in all states of Brazil and impairs plant development. Passion fruit woodiness disease causes leaf mosaic, blisters, deformation and reduced fruit size, making the produce unmarketable. Vines are typically eliminated only when the disease is detected in the early stages of their life cycle. The researchers propose systematic roguing – removal of weak, diseased or abnormal plants – throughout the life of the crop.

The study was funded by FAPESP and CAPES, the Brazilian Ministry of Education’s Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel. It was conducted by Brazilian researchers affiliated with the University of São Paulo’s Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ-USP), the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) at Araras, the University of Southwest Bahia (UESB), and the Semiarid Agriculture Unit of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), as well as colleagues at Argentina’s National Agricultural Technology Institute (INTA).

“Roguing is a technique that has been used to combat papaya disease in Espírito Santo state since the 1980s. After several experiments, it was found to be the best way to control papaya ringspot virus type P [PRSV-P],” said Jorge Alberto Marques Rezende, Full Professor at ESALQ-USP and principal investigator for the study, which began in 2010.

CABMV is transmitted by aphid saliva and spreads throughout an orchard in a few months. The aphid species in question do not colonize the plants but merely visit them, and insecticide is not effective for control purposes.

“Insecticide affects their nervous system but takes hours to kill them. Meanwhile, they’re stimulated to feed on more plants, spreading the virus farther, so insecticide helps propagate the disease instead of controlling it,” said David Marques de Almeida Spadotti, first author of the article. The research was part of Spadotti’s postdoctoral fellowship at ESALQ-USP.

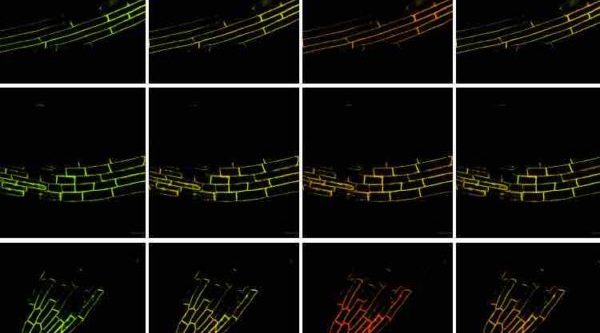

In previous experiments, the use of transgenic passion fruit plants and inoculation with attenuated variants of CABMV as a kind of vaccine also failed to control the disease. In this new study, an experimental orchard was planted in three areas belonging to ESALQ-USP in Piracicaba, São Paulo state, and two areas in Vitória da Conquista, southwestern Bahia. The experiments took place between 2013 and 2018. Approximately 100 healthy seedlings were planted in two areas of each city using trellises or T-shaped arbors connected by wires.

The vines were trained on the trellises and arbors for support but also to separate them so that the disease could easily be observed. Any buds with symptoms were identified and removed in weekly inspections.

In two other areas distant from the others, the same number of vines were planted using trellises and allowed to interlace without roguing, as in commercial plantations. The results of the two strategies were then compared.

In the absence of roguing, the virus spread throughout the crop in 120 days. In the areas submitted to systematic roguing, 8% of the vines were infected and removed after 180 days. In Piracicaba, only 16% had to be removed after 25 months, and the plants remained productive throughout this period.

The presence of CABMV in all infected or preventively removed vines was confirmed by PTA-ELISA serological testing.

“The symptoms appear eight days after inoculation of the virus on average. Roguing enables the grower to identify diseased plants visually and base control on visual inspection. Inspection should ideally be carried out at least once a week”

Spadotti said.

According to the researchers, the next step in the study entails larger pilot plantings of 1,000-2,000 passion fruit vines. In addition to eradicating diseased plants, they plan to replace them with healthy plants. The idea is to maintain the orchard for three to four years and compare it with another orchard maintained in the conventional manner, in which all plants are replaced every year.

“Because passion fruit is semiperennial, this longer production period is more advantageous from an economic standpoint than complete annual substitution,” said Rezende, principal investigator for the Thematic Project “Begomovirus and Crinivirus in Solanaceae”, which also relates to viruses in food crops.

The researchers stress, however, that if the strategy is to succeed, it should be implemented by all passion fruit growers in any given region. In addition to other plantations, the virus can spread from old or abandoned orchards, which should be eliminated.

CABMV-susceptible wild species of passion fruit in forests near plantations may also spread the disease. One of the experimental areas in Vitória da Conquista failed for this reason. When the wild plants were eliminated, the incidence of CABMV was considerably reduced.

According to IBGE, the national statistics and census bureau, Brazil is the world’s leading grower of passion fruit, with more than 550,000 metric tons produced in 2017.

Read the paper: Plant Pathology

Article source: Agência FAPESP

Author: André Julião

Image: Jorge Rezende

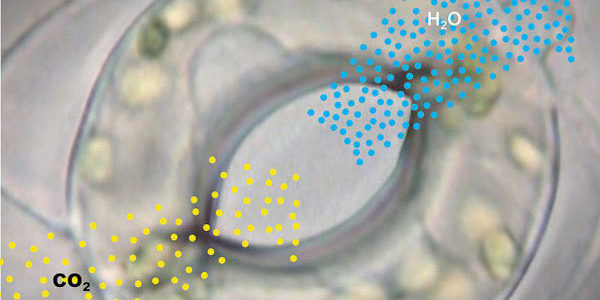

Plants face a dilemma in dry conditions: they have to seal themselves off to prevent losing too much water but this also limits their uptake of carbon dioxide. A sensory network assures that the plant strikes the right balance.

When water is scarce, plants can close their pores to prevent losing too much water. This allows them to survive even longer periods of drought, but with the majority of pores closed, carbon dioxide uptake is also limited, which impairs photosynthetic performance and thus plant growth and yield.

Plant accomplish a balancing act – navigating between drying out and starving in dry conditions – through an elaborate network of sensors. An international team of plant scientists led by Rainer Hedrich, a biophysicist from Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, has now pinpointed these sensors. The results have been published in the journal Nature Plants.

When light is abundant, plants open the pores in their leaves to take in carbon dioxide (CO2) which they subsequently convert to carbohydrates in a process called photosynthesis. At the same time, a hundred times more water escapes through the microvalves than carbon dioxide flows in.

This is not a problem when there is enough water available, but when soils are parched in the middle of summer, the plant needs to switch to eco-mode to save water. Then plants will only open their pores to perform photosynthesis for as long as necessary to barely survive. Opening and closing the pores is accomplished through specialised guard cells that surround each pore in pairs. The units comprised of pores and guard cells are called stomata.

The guard cells must be able to measure the photosynthesis and the water supply to respond appropriately to changing environmental conditions. For this purpose, they have a receptor to measure the CO2 concentration inside the leaf. When the CO2 value rises sharply, this is a sign that the photosynthesis is not running ideally. Then the pores are closed to prevent unnecessary evaporation. Once the CO2 concentration has fallen again, the pores reopen.

The water supply is measured through a hormone. When water is scarce, plants produce abscisic acid (ABA), a key stress hormone, and set their CO2 control cycle to water saving mode. This is accomplished through guard cells which are fitted with ABA receptors. When the hormone concentration in the leaf increases, the pores close.

The JMU research team wanted to shed light on the components of the guard cell control cycles. For this purpose, they exposed Arabidopsis species to elevated levels of CO2 or ABA. They did so over several hours to trigger reactions at the level of the genes. Afterwards, the stomata were isolated from the leaves to analyse the respective gene expression profiles of the guard cells using bioinformatics techniques. For this task, the team took Tobias Müller and Marcus Dietrich on board, two bioinformatics experts at the University of Würzburg.

The two experts found out that the gene expression patterns differed significantly at high CO2 or ABA concentrations. Moreover, they noticed that excessive CO2 also caused the expression of some ABA genes to change. These findings led the researchers to take a closer look at the ABA signalling pathway. They were particularly interested in the ABA receptors of the PYR/PYL family (pyrabactin receptor and pyrabactin-like). Arabidopsis has 14 of these receptors, six of them in the guard cells.

“Why does a guard cell need as many as six receptors for a single hormone? To answer this question, we teamed up with Professor Pedro Luis Rodriguez from the University of Madrid, who is an expert in ABA receptors,” says Hedrich. Rodriguez’s team generated Arabidopsis mutants in which they could study the ABA receptors individually.

“This enabled us to assign each of the six ABA receptors a task in the network and identify the individual receptors which are responsible for the ABA- and CO2-induced closing of the stomata,” Peter Ache, a colleague of Hedrich‘s, explains.

“We conclude from the findings that the guard cells offset the current photosynthetic carbon fixation performance with the status of the water balance using ABA as the currency,” Hedrich explains. “When the water supply is good, our results indicate that the ABA receptors evaluate the basic hormonal balance as quasi ‘stress-free’ and keep the stomata open for CO2 supply. When water is scarce, the drought stress receptors recognise the elevated ABA level and make the guard cells close the stomata to prevent the plant from drying out.”

Next, the JMU researchers aim to study the special characteristics of the ABA and CO2 relevant receptors as well as their signalling pathways and components.

Read the paper: Nature Plants

Article source: UNIVERSITY OF WÜRZBURG

Image: Rainer Hedrich & Peter Ache / Universität Würzburg

Findings from La Trobe University-led research could lead to less fertiliser wastage, saving millions of dollars for Australian farmers.

Published in the journal Plant Physiology, the findings provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms whereby plants sense how much and when to take in the essential nutrient, phosphorus, for optimal growth.

Lead author Dr Ricarda Jost, from the Department of Plant, Animal and Soil Sciences at La Trobe University said the environmental and economic benefits to farmers could be significant.

“In countries like Australia where soils are phosphorus poor, farmers are using large amounts of expensive, non-renewable phosphorus fertiliser, such as superphosphate or diammonium phosphate (DAP), much of which is not being taken up effectively by crops at the right time for growth,” Dr Jost said.

“Our findings have shown that a protein called SPX4 senses the nutrient status – the ‘amount of fuel in the tank’ of a crop – and alters gene regulation to either switch off or turn on phosphorus acquisition, and to alter growth and flowering time.”

Using Arabidopsis thaliana (thale or mouse-ear cress) shoots, the research team conducted genetic testing by adding phosphorus fertiliser and observing the behaviour of the protein.

For the first time, the SPX4 protein was observed to have both a negative and a positive regulatory effect on phosphorus take-up and resulting plant growth.

“The protein senses when the plant has taken in enough phosphorus and tells the roots to stop taking it up,” Dr Jost said. “If the fuel pump is turned off too early, this can limit plant growth.

“On the other hand, SPX4 seems to have a ‘moonlighting’ activity and can activate beneficial processes of crop development such as initiation of flowering and seed production.”

This greater understanding of how SPX4 operates could lead to a more precise identification of the genes it regulates, and an opportunity to control the protein’s activity using genetic intervention – switching on the positive and switching off the negative responses.

La Trobe agronomist Dr James Hunt said the research findings sit well with the necessity for Australian farmers’ to be as efficient as possible with costly fertiliser inputs.

“In our no-till cropping systems, phosphorus gets stratified in the top layers of soil. When this layer gets dry, crops cannot access these reserves and enter what we a call a phosphorus drought,” Dr Hunt said.

“The phosphorus is there, but crops can’t access it in the dry soil. If we could manipulate crop species to take up more phosphorus when the top soil is wet, we’d be putting more fuel in the tank for later crop growth when the top soil dries out.”

The research team will now be investigating in more detail how SPX4 interacts with gene regulators around plant development and controlling flowering time.

The research was published in Plant Physiology with collaborators from Zhejiang University (China), Ghent University & VIB Center for Plant Systems Biology (Belgium), French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Plant Energy Biology.

Read the paper: Plant Physiology

Article source: La Trobe University

Image: Free-Photos / Pixabay

This blog has been reposted with permission from the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory.

Unlike animals, plants can’t run away when things get bad. That can be the weather changing or a caterpillar starting to slowly munch on a leaf. Instead, they change themselves inside, using a complex system of hormones, to adapt to challenges.

Now, MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory scientists are connecting two plant defense systems to how these plants do photosynthesis. The study, conducted in the labs of Christoph Benning and Gregg Howe, is in the journal, The Plant Cell.

At the heart of this connection is the chloroplast, the engine of photosynthesis. It specializes in producing compounds that plants survive with. But plants have evolved ways to use it for other, completely unrelated purposes.

Their trick is to harvest their own chloroplasts’ protective membranes, made of lipids, the molecules found in fats and oils. Lipids have many uses, from making up cell boundaries, to being part of plant hormones, to storing energy.

If plants need lipids for some purpose other than serving as membranes, special proteins break down chloroplast membrane lipids. Then, the resulting products go to where they need to be for further processing.

For example, one such protein, breaks down lipids that end up in plant seed oil. Plant seed oil is both a basic food component and a precursor for biodiesel production.

Now, Kun (Kenny) Wang, a former Benning lab grad student, reports two more such chloroplast proteins with different purposes. Their lipid breakdown products help plants turn on their defense system against living pests and other herbivores. In turn, the proteins, PLIP2 and PLIP3, are themselves activated by another defense system against non-living threats.

In a nutshell, the plant plays a version of the popular children’s game, Telephone, with itself. In the real game, players form a line. The first person whispers a message into the ear of the next person in the line, and so on, until the last player announces the message to the entire group.

In plants, defense systems and chloroplasts also pass along chemical messages down a line. Breaking it down:

“The cross-talk between defense systems has a purpose. For example, there is mounting evidence that plants facing drought are more vulnerable to caterpillar attacks,” Kenny says. “One can imagine plants evolving precautionary strategies for varied conditions. And the cross-talk helps plants form a comprehensive defense strategy.”

Kenny adds, “The chloroplast is amazing. We suspect its membrane lipids spur functions other than defense or oil production. That implies more Telephone games leading to different ends we don’t know yet. We have yet to properly examine that area.”

“Those functions could help us better understand plants and engineer them to be more resistant to complex stresses.”

Kenny recently got his PhD from the MSU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. He has just started a post-doc position in the Farese-Walther lab at Harvard Medical School.

“They look at lipid metabolism in mammals and have started a project connecting it with brain disease in humans,” Kenny says. “There is increasing evidence that problems with lipid metabolism in the brain might lead to dementia, Alzheimer’s, etc.”

“I benefited a lot from my time at MSU. The community is very successful here: the people are nice, and you have support from colleagues and facilities. Although we scientists should sometimes be independent in our work, we also need to interact with our communities. No matter how good you are, there is a limit to your impact as an individual. That is one of the lessons I applied when looking for my post-doc.”

Photo of the author, Kun (Kenny) Wang. By Kenny Wang

Read the original article here.

By Atsuko Kanazawa, Igor Houwat, Cynthia Donovan

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

Atsuko Kanazawa is a plant scientist in the lab of David Kramer. Her main focus is on understanding the basics of photosynthesis, the process by which plants capture solar energy to generate our planet’s food supply.

This type of research has implications beyond academia, however, and the Kramer lab is using their knowledge, in addition to new technologies developed in their labs, to help farmers improve land management practices.

One component of the lab’s outreach efforts is its participation in the Legume Innovation Lab (LIL) at Michigan State University, a program which contributes to food security and economic growth in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

Atsuko recently joined a contingent that attended a LIL conference in Burkina Faso to discuss legume management with scientists from West Africa, Central America, Haiti, and the US. The experience was an eye opener, to say the least.

To understand some of the challenges faced by farmers in Africa, take a look at this picture, Atsuko says.

“When we look at corn fields in the Midwest, the corn stalks grow uniformly and are usually about the same height,” Atsuko says. “As you can see in this photo from Burkina Faso, their growth is not even.”

“Soil scientists tell us that much farmland in Africa suffers from poor nutrient content. In fact, farmers sometimes rely on finding a spot of good growth where animals have happened to fertilize the soil.”

Even if local farmers understand their problems, they often find that the appropriate solutions are beyond their reach. For example, items like fertilizer and pesticides are very expensive to buy.

That is where USAID’s Feed the Future and LIL step in, bringing economists, educators, nutritionists, and scientists to work with local universities, institutions, and private organizations towards designing best practices that improve farming and nutrition.

Atsuko says, “LIL works with local populations to select the most suitable crops for local conditions, improve soil quality, and manage pests and diseases in financially and environmentally sustainable ways.”

At the Burkina Faso conference, the Kramer lab reported how a team of US and Zambian researchers are mapping bean genes and identifying varieties that can sustainably grow in hot and drought conditions.

The team is relying on a new technology platform, called PhotosynQ, which has been designed and developed in the Kramer labs in Michigan.

PhotosynQ includes a hand-held instrument that can measure plant, soil, water, and environmental parameters. The device is relatively inexpensive and easy to use, which solves accessibility issues for communities with weak purchasing power.

The heart of PhotosynQ, however, is its open-source online platform, where users upload collected data so that it can be collaboratively analyzed among a community of 2400+ researchers, educators, and farmers from over 18 countries. The idea is to solve local problems through global collaboration.

Atsuko notes that the Zambia project’s focus on beans is part of the larger context under which USAID and LIL are functioning.

“From what I was told by other scientists, protein availability in diets tends to be a problem in developing countries, and that particularly affects children’s development,” Atsuko says. “Beans are cheaper than meat, and they are a good source of protein. Introducing high quality beans aims to improve nutrition quality.”

But, as LIL has found, good science and relationships don’t necessarily translate into new crops being embraced by local communities.

Farmers might be reluctant to try a new variety, because they don’t know how well it will perform or if it will cook well or taste good. They also worry that if a new crop is popular, they won’t have ready access to seed quantities that meet demand.

Sometimes, as Atsuko learned at the conference, the issue goes beyond farming or nutrition considerations. In one instance, local West African communities were reluctant to try out a bean variety suggested by LIL and its partners.

The issue was its color.

“One scientist reported that during a recent famine, West African countries imported cowpeas from their neighbors, and those beans had a similar color to the variety LIL was suggesting. So the reluctance was related to a memory from a bad time.”

This particular story does have a happy ending. LIL and the Burkina Faso governmental research agency, INERA, eventually suggested two varieties of cowpeas that were embraced by farmers. Their given names best translate as, “Hope,” and “Money,” perhaps as anticipation of the good life to come.

Another fruitful, perhaps more direct, approach of working with local communities has been supporting women-run cowpea seed and grain farms. These ventures are partnerships between LIL, the national research institute, private institutions, and Burkina Faso’s state and local governments.

Atsuko and other conference attendees visited two of these farms in person. The Women’s Association Yiye in Lago is a particularly impressive success story. Operating since 2009, it now includes 360 associated producing and processing groups, involving 5642 women and 40 men.

“They have been very active,” Atsuko remarks. “You name it: soil management, bean quality management, pest and disease control, and overall economic management, all these have been implemented by this consortium in a methodical fashion.”

“One of the local farm managers told our visiting group that their crop is wonderful, with high yield and good nutrition quality. Children are growing well, and their families can send them to good schools.”

As the numbers indicate, women are the main force behind the success. The reason is that, usually, men don’t do the fieldwork on cowpeas. “But that local farm manager said that now the farm is very successful, men were going to have to work harder and pitch in!”

Back in Michigan, Atsuko is back to the lab bench to continue her photosynthesis research. She still thinks about her Burkina Faso trip, especially how her participation in LIL’s collaborative framework facilitates the work she and her colleagues pursue in West Africa and other parts of the continent.

“We are very lucky to have technologies and knowledge that can be adapted by working with local populations. We ask them to tell us what they need, because they know what the real problems are, and then we jointly try to come up with tailored solutions.”

“It is a successful model, and I feel we are very privileged to be a part of our collaborators’ lives.”

This article is reposted with permission from the Michigan State University team. You can find the original post here: MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

Reposted with kind permission from the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory. Original article.

The need for speed: increasing plant yield is one way to increase food and fuel resources. But asking plants to simply do more of the usual is a strategy that can backfire. Photo by Romain Peli on Unsplash

When engineers want to speed something up, they look for the “pinch points”, the slowest steps in a system, and make them faster.

Say, you want more water to flow through your plumbing. You’d find the narrowest pipe and replace it with a bigger one.

Many labs are attempting this method with photosynthesis, the process that plants and algae use to capture solar energy.

All of our food and most of our fuels have come from photosynthesis. As our population increases, we need more food and fuel, requiring that we improve the efficiency of photosynthesis.

But, Dr. Atsuko Kanazawa and the Kramer Lab are finding that, for biological systems, the “pinch point” method can potentially do more harm than good, because the pinch points are there for a reason! So, how can this be done?

Atsuko and her colleagues at the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory (PRL) have been working on this problem for over 15 years. They have focused on a tiny machine in the chloroplast called the ATP synthase, a complex of proteins essential to storing solar energy in “high energy molecules” that power life on Earth.

That same ATP molecule and a very similar ATP synthase are both used by animals, including humans, to grow, maintain health, and move.

In plants, the ATP synthase happens to be one of the slowest process in photosynthesis, often limiting the amount of energy plants can store.

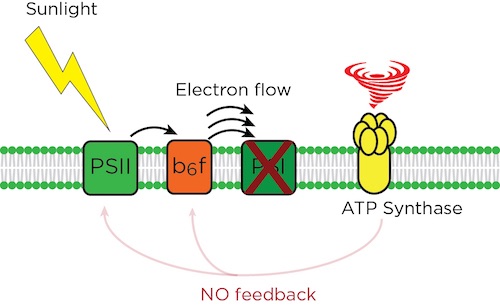

Photosynthetic systems trap sunlight energy that starts the reaction to move electrons forward in an assembly-line fashion to make useful energy compounds. The ATP synthase is one of the “pinch points” that slows the flow as needed, so plants stay healthy. In cfq, the absence of feedback leads to an electron pile up at PSI, and a crashed system. By MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory, except tornado graphic/CC0 Creative Commons

Atsuko thought, if the ATP synthase is such an important pinch point, what happens if it were faster? Would it be better at photosynthesis and give us faster growing plants?

Years ago, she got her hands on a mutant plant, called cfq, from a colleague. “It had an ATP synthase that worked non-stop, without slowing down, which was a curious example to investigate. In fact, under controlled laboratory conditions – very mild and steady light, temperature, and water conditions – this mutant plant grew bigger than its wild cousin.”

But when the researchers grew the plant under the more varied conditions it experiences in real life, it suffered serious damage, nearly dying.

“In nature, light and temperature quality change all the time, whether through the passing hours, or the presence of cloud cover or winds that blow through the leaves,” she says.

Atsuko’s research now shows that the slowness of the ATP synthase is not an accident; it’s an important braking mechanism that prevents photosynthesis from producing harmful chemicals, called reactive oxygen species, which can damage or kill the plant.

“It turns out that sunlight can be damaging to plants,” says Dave Kramer, Hannah Distinguished Professor and lead investigator in the Kramer lab.

“When plants cannot use the light energy they are capturing, photosynthesis backs up and toxic chemicals accumulate, potentially destroying parts of the photosynthetic system. It is especially dangerous when light and other conditions, like temperature, change rapidly.”

“We need to figure out how the plant presses on the brakes and tune it so that it responds faster…”

The ATP synthase senses these changes and slows down light capture to prevent damage. In that light, the cfqmutant’s fast ATP is a bad idea for the plant’s well-being.

“It’s as if I promised to make your car run faster by removing the brakes. In fact, it would work, but only for a short while. Then things go very wrong!” Dave says.

“In order to improve photosynthesis, what we need is not to remove the brakes completely, like in cfq, but to control them better,” Dave says. “Specifically, we need to figure out how the plant presses on the brakes and tune it so that it responds faster and more efficiently,” David says.

Atsuko adds: “Scientists are trying different methods to improve photosynthesis. Ultimately, we all want to tackle some long-term problems. Crucially, we need to continue feeding the Earth’s population, which is exploding in size.”

The study is published in the journal, Frontiers in Plant Science.

Dr. Sarah Schmidt (@BananarootsBlog), Researcher and Science Communicator at The Sainsbury Laboratory Science. Sarah got hooked on both banana research and science writing when she joined a banana Fusarium wilt field trip in Indonesia as a Fusarium expert. She began blogging at https://bananaroots.wordpress.com and just filmed her first science video. She speaks at public events like the Pint of Science and Norwich Science Festival.

Dr. Sarah Schmidt (@BananarootsBlog), Researcher and Science Communicator at The Sainsbury Laboratory Science. Sarah got hooked on both banana research and science writing when she joined a banana Fusarium wilt field trip in Indonesia as a Fusarium expert. She began blogging at https://bananaroots.wordpress.com and just filmed her first science video. She speaks at public events like the Pint of Science and Norwich Science Festival.

Every morning I slice a banana onto my breakfast cereal.

And I am not alone.

Every person in the UK eats, on average, 100 bananas per year.

Bananas are rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals like potassium and magnesium. Their high carbohydrate and potassium content makes them a favorite snack for professional sports players; the sugar provides energy and the potassium protects the players from muscle fatigue. Every year, around 5000 kg of bananas are consumed by tennis players at Wimbledon.

But bananas are not only delicious snacks and handy energy kicks. For around 100 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa, bananas are staple crops vital for food security. Staple crops are those foods that constitute the dominant portion of a standard diet and supply the major daily calorie intake. In the UK, the staple crop is wheat. We eat wheat-based products for breakfast (toast, cereals), lunch (sandwich), and dinner (pasta, pizza, beer).

In Uganda, bananas are staple crops. Every Ugandan eats 240 kg bananas per year. That is around 7–8 bananas per day. Ugandans do not only eat the sweet dessert banana that we know; in the East African countries such as Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda, the East African Highland banana, called Matooke, is the preferred banana for cooking. Highland bananas are large and starchy, and are harvested green. They can be cooked, fried, boiled, or even brewed into beer, so have very similar uses wheat in the UK.

In West Africa and many Middle and South American countries, another cooking banana, the plantain, is cooked and fried as a staple crop.

In terms of production, the sweet dessert banana we buy in supermarkets is still the most popular. This banana variety is called Cavendish and makes up 47% of the world’s banana production, followed by Highland bananas (24%) and plantains (17%). Last year, I visited Uganda and I managed to combine the top three banana cultivars in one dish: cooked and mashed Matooke, a fried plantain and a local sweet dessert banana!

Another important banana cultivar is the sweet dessert banana cultivar Gros Michel, which constitutes 12% of the global production. Gros Michel used to be the most popular banana cultivar worldwide until an epidemic of Fusarium wilt disease devastated the banana export plantations in the so-called “banana republics” in Middle America (Panama, Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica) in the 1950s.

Fusarium wilt disease is caused by the soil-borne fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (FOC). The fungus infects the roots of the banana plants and grows up through the water-conducting, vascular system of the plant. Eventually, this blocks the water transport of the plant and the banana plants start wilting before they can set fruits.

The Fusarium wilt epidemic in Middle America marked the rise of the Cavendish, the only cultivar that could be grown on soils infested with FOC. The fact that they are also the highest yielding banana cultivar quickly made Cavendish the most popular banana variety, both for export and for local consumption.

Currently, Fusarium wilt is once again the biggest threat to worldwide banana production. In the 1990s, a new race of Fusarium wilt – called Tropical Race 4 (TR4) – occurred in Cavendish plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia. Since then, TR4 has spread to the neighboring countries (Taiwan, the Philippines, China, and Australia), but also to distant locations such as Pakistan, Oman, Jordan, and Mozambique.

In Mozambique, the losses incurred by TR4 amounted to USD 7.5 million within just two years. Other countries suffer even more; TR4 causes annual economic losses of around USD 14 million in Malaysia, USD 121 million in Indonesia, and in Taiwan the annual losses amount to a whopping USD 253 million.

TR4 is not only diminishing harvests. It also raises the price of production, because producers have to implement expensive preventative measures and treatments of affected plantations. These preventive measures and treatments are part of the discussion at The World Banana Forum (WBF). The WBF is a permanent platform for all stakeholders of the banana supply chain, and is housed by the United Nation’s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). In December 2013, the WBF created a special taskforce to deal with the threat posed by TR4.

Despite its massive impact on banana production, we know very little about the pathogen that is causing Fusarium wilt disease. We don’t know how it spreads, why the new TR4 is so aggressive, or how we can stop it.

Breeding bananas is incredibly tedious, because edible cultivars are sterile and do not produce seeds. I am therefore exploring other ways to engineer resistance in banana against Fusarium wilt. As a scientist in the 2Blades group at The Sainsbury Laboratory, I am investigating how we can transfer resistance genes from other crop species into banana and, more recently, I have been investigating bacteria that are able to inhibit the growth and sporulation of F. oxysporum. These biologicals would be a fast and cost-effective way of preventing or even curing Fusarium wilt disease.

Twitter: @BananarootsBlog

Email: mailto:sarah.schmidt@tsl.ac.uk

Website: https://bananaroots.wordpress.com

This week’s blog was written by Dr Craig Cormick, the Creative Director of ThinkOutsideThe. He is one of Australia’s leading science communicators, with over 30 years’ experience working with agencies such as CSIRO, Questacon and Federal Government Departments.

So what do you think CRISPR cabbage might taste like? CRISPR-crispy? Altered in some way?

Participants at the recent Society for Experimental Biology/Global Plant Council New Breeding Technologies workshop in Gothenburg, Sweden, had a chance to find out, because in Sweden CRISPR-produced plants are not captured by the country’s GMO regulations and can be produced.

Professor Stefan Jansson, one of the workshop organizers, has grown the CRISPR cabbage (discussed in his blog for GPC!) and not only had it included on the menu of the workshop dinner, but also had samples for participants to take away. Some delegates were keen to pick up the samples while others were unsure how their own country’s regulatory rules would apply to them

That’s really CRISPR-edited cabbage on the menu. #SEBNBT17 Thanks Stefan Jansson pic.twitter.com/85KtpaTHWi

— Wayne Parrott (@ProfParrott) July 7, 2017

The uncertainty some delegates felt about the legality of taking a CRISPR cabbage sample home was a good demonstration of the diversity of regulations that apply – or may apply – to new breeding technologies, such as CRISPR and gene editing – and there was considerable discussion at the workshop on how European Union regulations and court rulings may play out, affecting both the development and export/import of plants and foods produced by the new technologies.

A lack of certainty has meant many researchers are unable to determine whether their work will need to be subjected to costly and time-consuming regulations or not.

The need for new breeding technologies was made clear at the workshop, which was attended by 70 people from 17 countries, with presentations on the need to double our current food production to feed the world in 2050 and reduce crop losses caused by problems such as viruses, which deplete crops by 10–15%.

The two-day workshop, held in early July, looked at a breadth of issues, including community attitudes, gene editing success stories, and tools and resources. But discussions kept coming back to regulation.

Regulations of gene technologies were largely developed 20 years ago or so, for different technologies than now exist, and as a result are not clear enough for researchers to determine whether different gene editing technologies they are working on may be governed by them or not.

The diversity of regulations is also going to be an issue, for some countries may allow different gene editing technologies, but others may not allow products developed using them to be imported.

That led to the group beginning to develop a statement that captured the feeling of the workshop, which, when complete, it is hoped will be adopted by relevant agencies around the world to develop their own particular positions on gene editing technologies. It would be a huge benefit to have a coherent and common line in an environment of mixed regulations in mixed jurisdictions.

And as to the initial question of what CRISPR cabbage tastes like – just like any cabbage you might buy at your local supermarket or farmers market, of course – since it is really no different.

#SEBNBT17 looks like normal cabbage but this gene edited! pic.twitter.com/i5pSy5c4bC

— GARNet (@GARNetweets) July 7, 2017

Want to read more about CRISPR? Check out our interview with Prof. Stefan Jansson or our introduction to CRISPR from Dr Damiano Martignago.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.

[RIO DE JANEIRO] A genetically modified (GM) cane variety that can kill the sugarcane borer (Diatraea saccharalis) has been approved in Brazil, to the delight of some scientists and the dismay of others, who say it may threaten Brazilian biodiversity.

Brazil is the second country, after Indonesia, to approve the commercial cultivation of GM sugarcane. The approval was announced by the Brazilian National Biosafety Technical Commission (CTNBio) on June 8.

Sugarcane borer is one of the main pests of the sugarcane fields of South-Central Brazil, causing losses of approximately US$1.5 billion per year.

“Breeding programmes could not produce plants resistant to this pest, and the existing chemical controls are both not effective and severely damaging to the environment,” says Adriana Hemerly, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, in an interview with SciDev.Net.

“Studies conducted outside Brazil prove that protein from genetically modified organisms harms non-target insects, soil fauna and microorganisms.”

Rogério Magalhães

“Therefore, the [GM variety] is a biotechnological tool that helps solve a problem that other technologies could not, and its commercial application will certainly have a positive impact on the productivity of sugarcane in the country.”

Jesus Aparecido Ferro, a member of CTNBio and professor at the Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho State University, believes the move followed a thorough debate that began in December 2015 — that was when the Canavieira Technology Center (Sugarcane Research Center) asked for approval to commercially cultivate the GM sugarcane variety.

“The data does not provide evidence that the cane variety has a potential to harm the environment or human or animal health,” Ferro told SciDev.Net.

To develop the variety, scientists inserted the gene for a toxin [Cry] from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) into the sugarcane genome, so it could produce its own insecticide against some insects’ larvae.

This is a technology that “has been in use for 20 years and is very safe”, says Aníbal Eugênio Vercesi, another member of the CTNBio, and a professor at the State University of Campinas.

But Valério De Patta Pillar, also a member of the CTNBio and a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, points to deficiencies in environmental risk assessment studies for the GM variety — and the absence of assessments of how consuming it might affect humans and animals.

According to Pillar, there is a lack of data about the frequency with which it breeds with wild varieties. Data is also missing on issues such as the techniques used to create the GM variety and the effects of its widespread use.

Rogério Magalhães, an environmental analyst at Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment, also expressed concern about the approval of the commercial transgenic cane.

“I understand that studies related to the impacts that genetically modified sugarcane might have on Brazilian biodiversity were not done by the company that owns the technology,” said Magalhães in an interview with SciDev.Net. This is very important because Brazil’s climate, species, and soils differ from locations where studies might have taken place, he explained.

Among the risks that Magalhães identified is contamination of the GM variety’s wild relatives. “The wild relative, when contaminated with transgenic sugarcane, will have a competitive advantage over other uncontaminated individuals, as it will exhibit resistance to insect-plague that others will not have,” he explained.

Another risk that Magalhães warns about is damage to biodiversity. “Studies conducted outside Brazil prove that Cry protein from genetically modified organisms harms non-target insects, soil fauna and microorganisms.”

Magalhães added that some pests have already developed resistance to the Bt Cry protein, prompting farmers to apply agrochemicals that are harmful to the environment and human health.

This piece was originally published by SciDev.Net’s Latin America and Caribbean desk.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.