Some native plants do not appear to be adapting to warming conditions.

Native Australian alpine plants may not be able to adapt or migrate quickly enough to survive rapid changes in climate change, a UNSW study has found.

The study of 21 plants from Kosciuszko National Park, published in Ecology and Evolution, found that 20 were not responding to warming conditions.

Only one species – the Star Plantain (Plantago muelleri) – showed that it was adapting to warmer conditions by displaying an increase in plant size.

The second plant that showed evidence of a change in plant traits was the Cascade Everlasting (Ozothamnus secundiflorus), but it decreased in leaf thickness over a 125-year time period.

“We predicted leaves would become more thicker, as this would be advantageous if plants were facing longer growing seasons and increasing temperatures,” lead author Meena Sritharan said.

“Our findings suggest that native alpine plants may not be adapting to the substantial local climate change occurring in Australian alpine regions.

“Australian native alpine plants face a bleak future in the face of rapid climate change.”

Ms Sritharan is a PhD research scholar at ANU who participated in the study as an honours student in the Evolution & Ecology Research Centre at UNSW Science’s School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences.

The point of the study was to gauge whether alpine plants in the southern hemisphere had changed in morphology, or their physical form, over time in response to recent climate warming.

Ms Sritharan said the 21 alpine plants exist in one of the ecosystems known to be least resistant to the effects of climate change.

“Alpine environments are facing higher-than-average increases in temperature in the last century,” Ms Sritharan said.

“But rapid changes in the environment can promote rapid changes in species.”

“Consequently, we expected that a rapid increase in temperature would result in a change in the plant traits we measured, such as size and leaf shape. These changes in plant traits would suggest that alpine plants may be changing in response to a changing climate.”

Previous studies have also shown that both native and invasive plants are capable of rapid changes in their morphology.

The researchers used herbarium (preserved) plant specimens collected between 1890 and 2016, and modern specimens collected in February, 2017.

Examples of the alpine plants they studied included Cushion Caraway (Oreomyrrhis pulvinifica), Alpine Rice flower (Pimelea alpine), Carpet Heath (Pentrachondra pumila) and Snow Aciphyll (Aciphylla glacialis).

The researchers measured five different plant traits: plant size, leaf shape, leaf area, leaf width and specific leaf area (the ratio of the leaf area to leaf dry mass).

Ms Sritharan said the study findings are surprising as the results were contrary to what they expected and what species in the northern hemisphere are facing.

She said plants in the northern hemisphere are changing substantially and adapting to changed environmental conditions brought by climate change.

“For instance, some British plant species (such as White Nettle (Lamium album) and Kenilworth ivy (Cymbalaria muralis) are flowering earlier than expected in the past decade compared to the previous four decades,” Ms Sritharan said.

“The plant height of species growing in tundra ecosystems (treeless regions in cold climates) have also increased with warming over the past three decades.”

Scientists also forecast that plant species will migrate to higher elevations to escape the effects of climate warming.

But Ms Sritharan said she was surprised to find that a shrub – Cascade Everlasting (Ozothamnus secundiflorus) – had moved downslope over time rather than to a higher elevation.

“This indicates that we should look into if, and where, other native Australian alpine species may be migrating to, in the face of climate change,” she said.

Ms Sritharan’s supervisor, the director of UNSW’s Evolution & Ecology Research Centre, Professor Angela Moles, is currently investigating whether Australian alpine plants are shifting their distributions uphill.

“This summer we will be doing heatwave experiments to measure how Australian alpine plants respond to an increased duration of heatwaves, which is what climate researchers forecast for the future,” Prof. Moles said.

Read the paper: Ecology and Evolution

Article source: University of New South Wales

Author: Diane Nazaroff

Image credit: allylester / Pixabay

For young plants, timing is just about everything. Now, scientists have found that herbivores, animals that consume plants, have a lot to say about evolution at this vulnerable life stage.

Once a plant seedling breaches the soil surface and begins to grow, a broad range of factors will determine whether it thrives or perishes.

Scientists have long perceived that natural selection favors early rising seeds. Seedlings that emerge early in the growing season should have a competitive advantage in monopolizing precious soil resources. Early growth also should mean more access to light, since early growers can block sunlight for seedlings that emerge later in the season.

Despite plenty of proof that germinating early is highly advantageous, many plants germinate later. Why?

University of California San Diego researchers found in a recent study that herbivores have a lot to say in determining how germination time contributes to plant growth.

Research published in the journal Evolution Letters by former UC San Diego graduate student Joseph Waterton and Division of Biological Sciences Professor Elsa Cleland has shown that certain vertebrate herbivores—including mice, rabbits and birds—play an underappreciated role in shaping natural selection in plant growth. Due to earlier seasonal growth patterns emerging from climate change, the new findings may factor into evolutionary responses to global environmental changes.

“Germination timing is a really important trait that influences the fitness of plants and their ability to survive and reproduce,” said Waterton, who received his PhD in Biological Sciences and is now at Indiana University. “Until this study we didn’t understand the role herbivores played in the evolution of this trait—we had very little idea of what shaped this trait besides aspects of the abiotic environment, such as climate.”

In field studies using two California grass species, Waterton and Cleland found that early emerging seedlings were more impacted by vertebrate herbivores compared to those that emerged later, likely because they were the first and biggest bits of greenery available on the landscape at the start of the growing season when not much else was growing. They found that such early season consumption by herbivores shrinks the benefit of early seedling emergence.

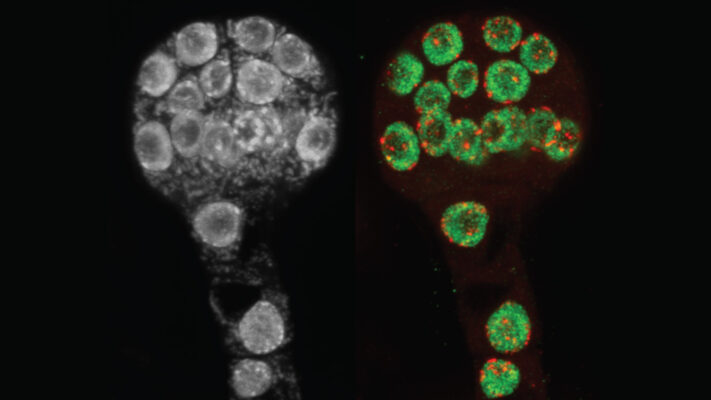

Conducted at the UC San Diego Biology Field Station in early 2018, the researchers’ study examined native Stipa pulchra and non‐native Bromus diandrus grasses, common California grass species with vastly different origins and growth strategies, in neighboring plots that either excluded or allowed access to vertebrate herbivores. Herbivores consistently weakened the success of early emergers in both grass species, the results showed.

With climate change forces shifting the timing of many plant life stages earlier in the year, the new study shows that herbivores are likely working as a counteracting force.

“Plants that germinate earlier than their neighbors tend to win out. But our study shows that herbivory early in the growing season can counteract the advantage of early germination,” said Cleland, a professor in the Ecology, Behavior and Evolution Section. “This is important because in order to persist and keep pace with climate change, many species will need to shift their seasonal timing. Our study shows that we can’t accurately estimate the strength of natural selection on key traits if we don’t account for realistic forces acting in nature, such as herbivory on plants.”

The study was funded by a graduate student researcher fellowship from the University of California’s Institute for the Study of Ecological Effects of Climate Impacts (ISEECI) and a Jeanne M. Messier Memorial Fellowship.

Read the paper: Evolution Letters

Article source: UC San Diego

Image: At UC San Diego’s Biology Field Station, scientists tested California grasses in plots that allowed or excluded the influence of birds, mice, rabbits and other plant consumers. Credit: UC San Diego