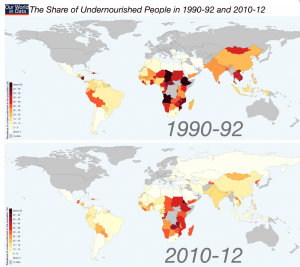

Herbivorous pests can devastate crops, with huge economic and social impacts that threaten global food security. In 2011 scientists warned that biological threats, including pests and pathogens, account for a 40% loss in global production and have the potential for even higher losses in the future.

A farmer sprays pesticides on her crop. From IFPRI – IMAGES. Used under Creative Commons 2.0.

In the 1950s and 1960s huge amounts of pesticides were being used in agriculture, with negative effects on both humans and ecology. Pests and pathogens were developing resistance to pesticides, and to counteract this chemical companies were developing ever stronger, more expensive chemicals.

Perry Adkisson and Ray Smith, both entomologists, noted the harmful effects on the economy and environment of the overuse of synthetic pesticides. Working together they identified practical approaches to pest control that minimized pesticide use. They developed and popularized integrated pest management (IPM) systems, for which they won the World Food prize in 1997.

“Integrated Pest Management (IPM) means the careful consideration of all available pest control techniques and subsequent integration of appropriate measures that discourage the development of pest populations and keep pesticides and other interventions to levels that are economically justified and reduce or minimize risks to human health and the environment. IPM emphasizes the growth of a healthy crop with the least possible disruption to agro-ecosystems and encourages natural pest control mechanisms.” FAO definition

What is IPM?

IPM is an approach to crop production that considers the whole ecosystem, integrating a number of management techniques, rather than focusing all resources on a single practice such as pesticide use. Adkisson and Smith identified a number of principals around which successful IPM should be based:

Firstly, crop varieties should be selected that are appropriate to the culture and local environment. This would ensure the crop species is already adapted to local conditions, and may have some defense mechanisms to protect itself from biotic and abiotic stresses.

Secondly, IPM is based around pest control rather than complete eradication. Therefore, maximum tolerable levels of the pest that still enable good crop yields should be identified and the pests should be allowed to survive at this threshold level, although allowing a number of pests to exist within the crop requires continual monitoring. Good knowledge of pest behavior and lifecycle enables the prediction of where more or less controls are required.

Finally, when choosing a method of control, both mechanical methods, such as traps or barriers, or appropriate biological control are preferential. However, pesticides can be integrated into the plan if necessary, providing use is responsible and not in excess of requirements. Some really cool practices are now emerging that can be used as part of an IPM system around the world.

Enhancing biological control

Simply reducing pesticide use can actually lead to increased yields, as farmers in Vietnam discovered when scientists convinced them to try it for themselves. Their nemesis, the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens), is increasingly resistant to insecticides, with devastating outbreaks becoming more common. Rice farmers found that by stopping their typical regular insecticide sprays, the planthopper’s natural predators such as frogs, spiders, wasps and dragonflies were able to survive and remove the pests, giving farmers a 10% increase in harvest income. This improved biological control is a key component of IPM.

The Brown Planthopper (Nilaparvata lumens) on a rice stem. From IRRI photos. Used under Creative Commons 2.0.

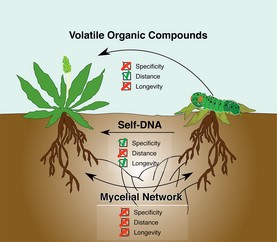

Push-pull technology

Push-pull agriculture has been very successful in Kenya, where stemborer moths can cause vast yield losses in maize with estimated economic impacts of up to US$ 40.8 million per year. Push-pull technology uses selected species as intercrops between the main crops of interest. Intercrops work in two ways, by pushing pests away from the economically valuable crop, and pulling them towards a less valuable intercrop. The stemborer moth push-pull system uses Desmodium (Desmodium uncinatum) to repel stemborer moths. Desmodium species are small flowering plants that produce secondary metabolites that repel insects. Moths are then attracted to the surrounding napier grass instead.

Aside from controlling the stemborer moth, this system has a number of additional benefits. Desmodium suppresses the growth of Striga grass (a devastating weed that you can read about here) via a number of mechanisms, primarily through interfering with root growth. Additionally, the intercrop species can be used for animal fodder and improve soil fertility. The multiple benefits and success of this system has meant push pull has now been adopted by over 80,000 small-holdings in Kenya and is being rolled out to Uganda, Tanzania and Ethiopia.

Stem borer larva feeding on a maize stem. From International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. Used under Creative Commons 2.0.

Abrasive weeding

Abrasive weeding is a relatively new technique that involves firing air-propelled grit at a crop to physically kill any weeds growing between crop rows. One issue with this method is that it indiscriminately damages the stem and leaf tissue of both crops and weeds, but grit applicator nozzles are available to more directly target the base of the stem to minimize collateral damage. A recent study found abrasive weed control reduced weed density by up to 80% in tomato and pepper fields, with 33-44% increases in yield.

Maize cob or walnut shells are currently the most frequently used grits, but the technique offers the exciting possibility of combining fertilization and weed control in one step, which could reduce time and cost to the farmer. For example, soybean meal is able to destroy plant tissues when fired from the gun, and has high nitrogen content that is released slowly into the soil over a period of at least three months, making it an ideal source of fertilizer.

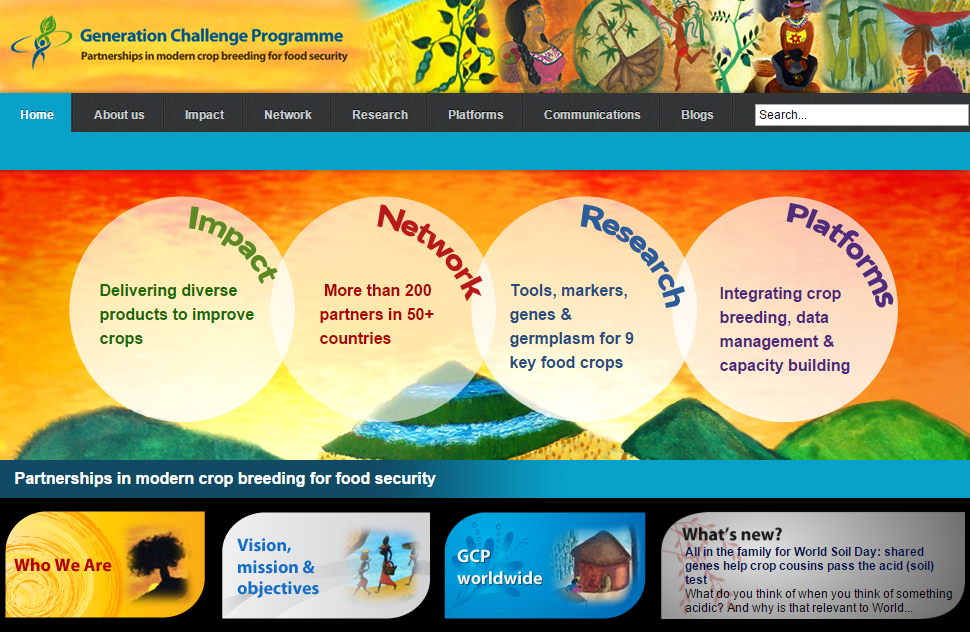

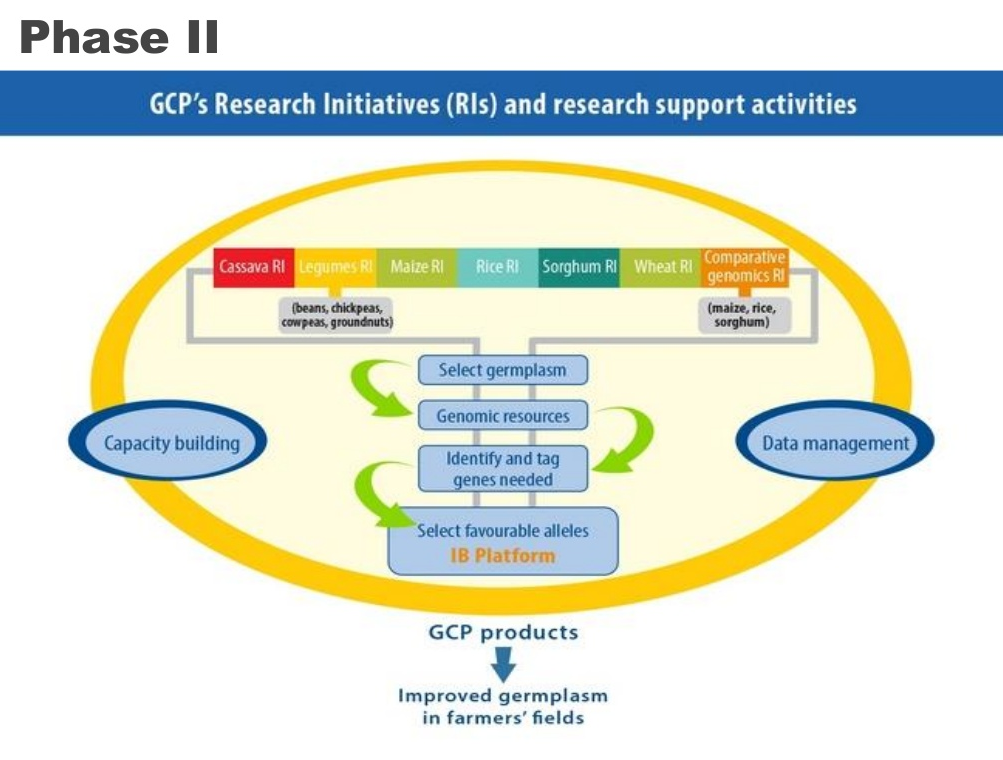

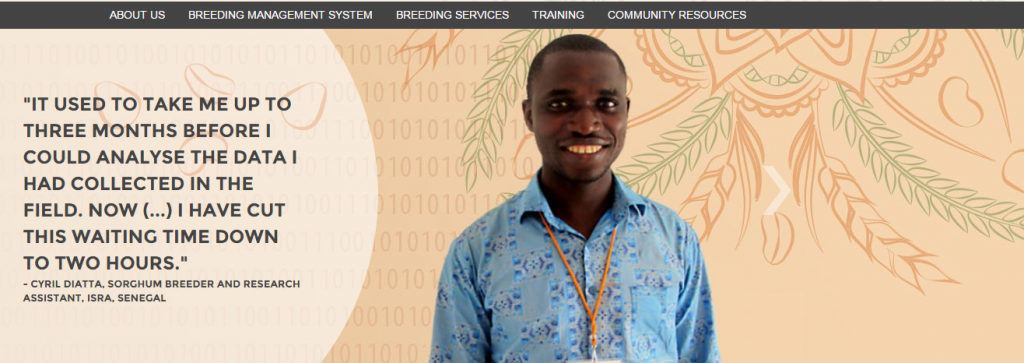

The IBP is hosted on the cyberinfrastructure provided by the

The IBP is hosted on the cyberinfrastructure provided by the