Use of saline water to irrigate crops would bolster food security for many arid countries; however, this has not been possible due to the detrimental effects of salt on plants. Now, researchers at KAUST, along with scientists in Egypt, have shown that saline irrigation of tomato is possible with the help of a beneficial desert root fungus. This represents a new key technology for countries lacking water resources.

“Salt in irrigation water is one of the most significant abiotic stresses in arid and semiarid farming,” says former KAUST postdoc Mohamed Abdelaziz, who worked on the project team alongside Heribert Hirt. “Improving plant salt tolerance and increasing the yield and quality of crops is vital, but we must achieve this in a sustainable, inexpensive way.”

The root fungus Piriformospora indica forms beneficial symbiotic relationships with many plant species, and previous research indicates it boosts plant growth under salt stress conditions in barley and rice. While initial studies suggest the fungus can improve growth in tomato plants under long-term saline irrigation, the mechanisms behind the process are unclear. Also, little is known about the fungal-plant interaction throughout the entire growing season.

“Plant salt tolerance is a complex trait influenced by many factors,” says Abdelaziz. “The salt-tolerance mechanism depends on the correct activation of salt tolerance genes, stresses on cell membranes and the buildup of toxic sodium ions. We monitored growth performance over four months in tomato plants colonized with P. indica and in an untreated control group, both grown commercial style in greenhouses. We examined genetic and enzymatic responses to salt stress in both groups.”

The main threat to plants under salt stress is the buildup of sodium ions, which affects plant metabolism, and leaf and fruit growth. For example, excessive sodium in shoots and roots disrupts levels of potassium, which is vital for multiple growth processes from germination to enzyme activation.

The team showed that colonization by P. indica increased the expression of a gene in leaves called LeNHX1, one of a family of genes responsible for removing sodium from cells. Furthermore, potassium levels in leaves, shoots and roots of the P. indica group were higher than in controls. P. indica also increased levels of antioxidant enzyme activity, offering further protection.

“Colonization with P. indica boosted tomato fruit yield by 22 percent under normal conditions and 65 percent under saline conditions,” says Abdelaziz. “Colonizing vegetables provides a simple, low-cost method suitable for all producers, from smallholders to large-scale farming.”

Read the paper: Scientia Horticulturae

Article source: KAUST

Image credit: Capri23auto / Pixabay

Another fantastic year of discovery is over – read on for our 2016 plant science top picks!

A Zostera marina meadow in the Archipelago Sea, southwest Finland. Image credit: Christoffer Boström (Olsen et al., 2016. Nature).

The year began with the publication of the fascinating eelgrass (Zostera marina) genome by an international team of researchers. This marine monocot descended from land-dwelling ancestors, but went through a dramatic adaptation to life in the ocean, in what the lead author Professor Jeanine Olsen described as, “arguably the most extreme adaptation a terrestrial… species can undergo”.

One of the most interesting revelations was that eelgrass cannot make stomatal pores because it has completely lost the genes responsible for regulating their development. It also ditched genes involved in perceiving UV light, which does not penetrate well through its deep water habitat.

Read the paper in Nature: The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea.

BLOG: You can find out more about the secrets of seagrass in our blog post.

Plants are known to form new organs throughout their lifecycle, but it was not previously clear how they organized their cell development to form the right shapes. In February, researchers in Germany used an exciting new type of high-resolution fluorescence microscope to observe every individual cell in a developing lateral root, following the complex arrangement of their cell division over time.

Using this new four-dimensional cell lineage map of lateral root development in combination with computer modelling, the team revealed that, while the contribution of each cell is not pre-determined, the cells self-organize to regulate the overall development of the root in a predictable manner.

Watch the mesmerizing cell division in lateral root development in the video below, which accompanied the paper:

Read the paper in Current Biology: Rules and self-organizing properties of post-embryonic plant organ cell division patterns.

In March, a Spanish team of researchers revealed how the anti-wilting molecular machinery involved in preserving cell turgor assembles in response to drought. They found that a family of small proteins, the CARs, act in clusters to guide proteins to the cell membrane, in what author Dr. Pedro Luis Rodriguez described as “a kind of landing strip, acting as molecular antennas that call out to other proteins as and when necessary to orchestrate the required cellular response”.

Read the paper in PNAS: Calcium-dependent oligomerization of CAR proteins at cell membrane modulates ABA signaling.

*If you’d like to read more about stress resilience in plants, check out the meeting report from the Stress Resilience Forum run by the GPC in coalition with the Society for Experimental Biology.*

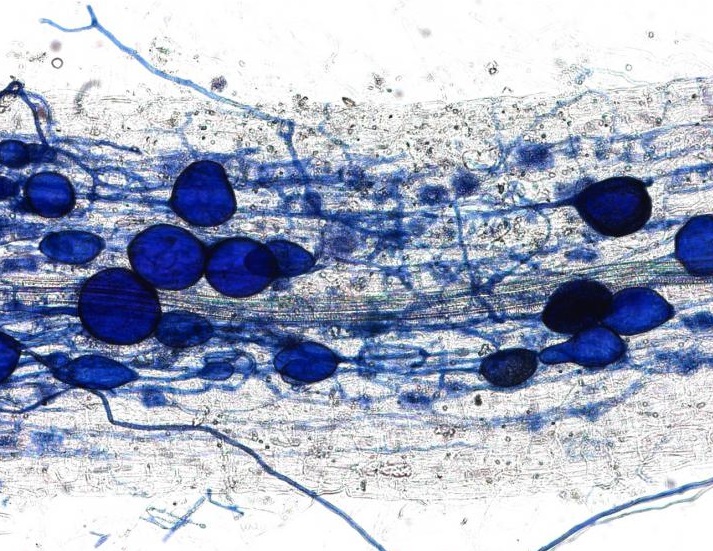

This plant root is infected with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Image credit: University of Zurich.

In April, we received an amazing insight into the ‘decision-making ability’ of plants when a Swiss team discovered that plants can punish mutualist fungi that try to cheat them. In a clever experiment, the researchers provided a plant with two mutualistic partners; a ‘generous’ fungus that provides the plant with a lot of phosphates in return for carbohydrates, and a ‘meaner’ fungus that attempts to reduce the amount of phosphate it ‘pays’. They revealed that the plants can starve the meaner fungus, providing fewer carbohydrates until it pays its phosphate bill.

Author Professor Andres Wiemsken explains: “The plant exploits the competitive situation of the two fungi in a targeted manner, triggering what is essentially a market-based process determined by cost and performance”.

Read the paper in Ecology Letters: Options of partners improve carbon for phosphorus trade in the arbuscular mycorrhizal mutualism.

The transition of ancient plants from water onto land was one of the most important events in our planet’s evolution, but required a massive change in plant biology. Suddenly plants risked drying out, so had to develop new ways to survive drought.

In May, an international team discovered a key gene in moss (Physcomitrella patens) that allows it to tolerate dehydration. This gene, ANR, was an ancient adaptation of an algal gene that allowed the early plants to respond to the drought-signaling hormone ABA. Its evolution is still a mystery, though, as author Dr. Sean Stevenson explains: “What’s interesting is that aquatic algae can’t respond to ABA: the next challenge is to discover how this hormone signaling process arose.”

Read the paper in The Plant Cell: Genetic analysis of Physcomitrella patens identifies ABSCISIC ACID NON-RESPONSIVE, a regulator of ABA responses unique to basal land plants and required for desiccation tolerance.

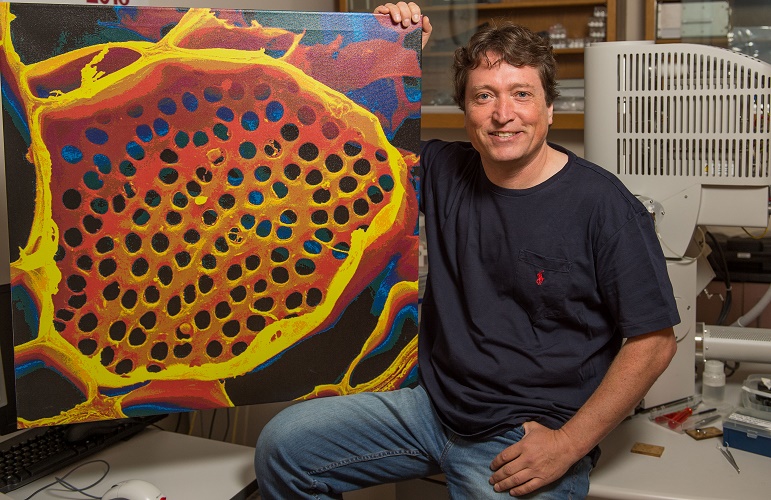

Professor Michael Knoblauch shows off a microscope image of phloem tubes. Image credit: Washington State University.

Sometimes revisiting old ideas can pay off, as a US team revealed in June. In 1930, Ernst Münch hypothesized that transport through the phloem sieve tubes in the plant vascular tissue is driven by pressure gradients, but no-one really knew how this would account for the massive pressure required to move nutrients through something as large as a tree.

Professor Michael Knoblauch and colleagues spent decades devising new methods to investigate pressures and flow within phloem without disrupting the system. He eventually developed a suite of techniques, including a picogauge with the help of his son, Jan, to measure tiny pressure differences in the plants. They found that plants can alter the shape of their phloem vessels to change the pressure within them, allowing them to transport sugars over varying distances, which provided strong support for Münch flow.

Read the paper in eLife: Testing the Münch hypothesis of long distance phloem transport in plants.

BLOG: We featured similar work (including an amazing video of the wound response in sieve tubes) by Knoblauch’s collaborator, Dr. Winfried Peters, on the blog – read it here!

Preserved remains of rope, seeds, reeds and pellets (left), and a desiccated barley grain (right) found at Yoram Cave in the Judean Desert. Credit: Uri Davidovich and Ehud Weiss.

In July, an international and highly multidisciplinary team published the genome of 6,000-year-old barley grains excavated from a cave in Israel, the oldest plant genome reconstructed to date. The grains were visually and genetically very similar to modern barley, showing that this crop was domesticated very early on in our agricultural history. With more analysis ongoing, author Dr. Verena Schünemann predicts that “DNA-analysis of archaeological remains of prehistoric plants will provide us with novel insights into the origin, domestication and spread of crop plants”.

Read the paper in Nature Genetics: Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley.

BLOG: We interviewed Dr. Nils Stein about this fascinating work on the blog – click here to read more!

Another exciting cereal paper was published in August, when an Australian team revealed that C4 photosynthesis occurs in wheat seeds. Like many important crops, wheat leaves perform C3 photosynthesis, which is a less efficient process, so many researchers are attempting to engineer the complex C4 photosynthesis pathway into C3 crops.

This discovery was completely unexpected, as throughout its evolution wheat has been a C3 plant. Author Professor Robert Henry suggested: “One theory is that as [atmospheric] carbon dioxide began to decline, [wheat’s] seeds evolved a C4 pathway to capture more sunlight to convert to energy.”

Read the paper in Scientific Reports: New evidence for grain specific C4 photosynthesis in wheat.

Professor Stefan Jansson cooks up “Tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables”. Image credit: Stefan Jansson.

September marked an historic event. Professor Stefan Jansson cooked up the world’s first CRISPR meal, tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables (genome-edited cabbage). Jansson has paved the way for CRISPR in Europe; while the EU is yet to make a decision about how CRISPR-edited plants will be regulated, Jansson successfully convinced the Swedish Board of Agriculture to rule that plants edited in a manner that could have been achieved by traditional breeding (i.e. the deletion or minor mutation of a gene, but not the insertion of a gene from another species) cannot be treated as a GMO.

Read more in the Umeå University press release: Umeå researcher served a world first (?) CRISPR meal.

BLOG: We interviewed Professor Stefan Jansson about his prominent role in the CRISPR/GM debate earlier in 2016 – check out his post here.

*You may also be interested in the upcoming meeting, ‘New Breeding Technologies in the Plant Sciences’, which will be held at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, on 7-8 July 2017. The workshop has been organized by Professor Jansson, along with the GPC’s Executive Director Ruth Bastow and Professor Barry Pogson (Australian National University/GPC Chair). For more info, click here.*

Phytochromes help plants detect day length by sensing differences in red and far-red light, but a UK-Germany research collaboration revealed that these receptors switch roles at night to become thermometers, helping plants to respond to seasonal changes in temperature.

Dr Philip Wigge explains: “Just as mercury rises in a thermometer, the rate at which phytochromes revert to their inactive state during the night is a direct measure of temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower phytochromes revert to inactivity, so the molecules spend more time in their active, growth-suppressing state. This is why plants are slower to grow in winter”.

Read the paper in Science: Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis.

A fossil ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) leaf with its modern counterpart. Image credit: Gigascience.

In November, a Chinese team published the genome of Ginkgo biloba¸ the oldest extant tree species. Its large (10.6 Gb) genome has previously impeded our understanding of this living fossil, but researchers will now be able to investigate its ~42,000 genes to understand its interesting characteristics, such as resistance to stress and dioecious reproduction, and how it remained almost unchanged in the 270 million years it has existed.

Author Professor Yunpeng Zhao said, “Such a genome fills a major phylogenetic gap of land plants, and provides key genetic resources to address evolutionary questions [such as the] phylogenetic relationships of gymnosperm lineages, [and the] evolution of genome and genes in land plants”.

Read the paper in GigaScience: Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba.

The year ended with another fascinating discovery from a Danish team, who used fluorescent tags and microscopy to confirm the existence of metabolons, clusters of metabolic enzymes that have never been detected in cells before. These metabolons can assemble rapidly in response to a stimulus, working as a metabolic production line to efficiently produce the required compounds. Scientists have been looking for metabolons for 40 years, and this discovery could be crucial for improving our ability to harness the production power of plants.

Read the paper in Science: Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum.

Another amazing year of science! We’re looking forward to seeing what 2017 will bring!

P.S. Check out 2015 Plant Science Round Up to see last year’s top picks!

The Journal of Experimental Botany (JXB) published a special issue in June entitled ‘Breeding plants to cope with future climate change’

By Jonathan Ingram

The Journal of Experimental Botany (JXB) recently published a special issue entitled ‘Breeding plants to cope with future climate change’.

More often than not, climate change discussions are focused on debating the degree of change we are likely to experience, unpredictable weather scenarios, and politics. However, regardless of the hows and whys, it is now an undeniable fact that the climate will change in some way.

This JXB special issue focuses on the necessary and cutting edge research needed to breed plants that can cope under new conditions, which is essential for continued production of food and resources in the future.

The breadth of research required to address this problem is wide. The 12 reviews included in the issue cover aspects such as research planning and putting together integrated research programs, and more specific topics, such as the use of traditional landraces in breeding programs. Alongside these reviews, original research addresses some of the key questions using novel techniques and methodology. Critically, the research presented comes from a diversity of labs around the world, from European wheat fields to upland rice in Brazil. Taking a global view is essential in our adaptation to climate change.

Avoiding starvation

Why release this special issue now?

Quite simply, the consequences of an inadequate response to climate change are stark for the human population. In fact, as previously discussed on the Global Plant Council blog, changing climate and extreme weather events are already having an impact on food production. For example, drought in Australia (2007), Russia (2010) and South-East China (2013) all resulted in steep increases in food prices. However, a positive side effect of this was to put food security at the top of the global agenda.

A farm in China during drought. Reduced food production can cause steep rises in food prices leading to socio-economic problems.

Photo credit: Bert van Dijk used under Creative Commons License 2.0

Moving forwards, researchers and breeders alike will have to change their fundamental approach to developing novel varieties of crops. In the past, breeders have been highly succesful in increasing yields to feed a growing population. However, we now need to adapt to a rapidly changing and unpredictable environment.

Dr Bryan McKersie sums this up in his contribution to the special issue. He commented: “Current plant breeding methods use large populations and rigorous selection in field environments, but the future environment is different and does not exist yet. Lessons learned from the Green Revolution and development of genetically engineered crops suggest that a new interdisciplinary research plan is needed to achieve food security.”

Driving up yields

So which traits should we be studying to increase resilience to climate change in our crops?

A potentially important characteristic brought to the foreground by Dr Karine Chenu and colleagues (University of Queensland, Australia) is susceptibility to frost damage. Although seemingly counterintuitive at first, the changing climate could result in greater frost exposure at key phases of the crop lifecycle. Warmer temperatures, or clear and cool nights during a drought, would allow vulnerable tissue to emerge earlier in the spring (Gu et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2012). A late frost could then be incredibly destructive to our agricultural systems, causing losses of up to 85% (Paulsen and Heyne, 1983; Boer et al., 1993).

As explained by Dr Chenu, “Finding frost tolerant lines would thus help to deal with frost damage but also with losses due to extreme heat and drought – as they could be avoided by earlier sowings”.

The authors conclude that a “national yield advantage of up to 20% could result from the breeding of frost tolerant lines if useful genetic variation can be found”. The impact of this for future agriculture is incredibly exciting.

This study is just one illustration of the importance of thinking outside the box and investigating a wide range of traits when looking to adapt crops to climate change.

You can find the full Breeding plants to cope with future climate change Special Issue of Journal of Experimental Botany here. Much of the research in the issue is freely available (open access).

Journal of Experimental Botany publishes an exciting mix of research, review and comment on fundamental questions of broad interest in plant science. Regular special issues highlight key areas.

References

Association of Applied Biologists. 2014. Breeding plants to cope with future climate change. Newsletter of the Association of Applied Biologists 81, Spring/Summer 2014.

Boer R, Campbell LC, Fletcher DJ. 1993. Characteristics of frost in a major wheat-growing region of Australia. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 44, 1731–1743.

Gu L, Hanson PJ, Post WM et al. 2008. The 2007 Eastern US spring freeze: increased cold damage in a warming world? BioScience 58, 253–262.

Paulsen GM, Heyne EG. 1983. Grain production of winter wheat after spring freeze injury. Agronomy Journal 75, 705–707.

Zheng BY, Chenu K, Dreccer MF, Chapman SC. 2012. Breeding for the future: what are the potential impacts of future frost and heat events on sowing and flowering time requirements for Australian bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) varieties? Global Change Biology 18, 2899–2914.