A newly discovered protein turns on plants’ cellular defence to excessive light and other stress factors caused by a changing climate, according to a new study published in eLife.

Plants play a crucial role in supporting life on earth by using energy from sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugars and oxygen – a process called photosynthesis. This provides a crucial food supply for humans and animals, and makes the atmosphere more hospitable to living creatures. Understanding how plants respond to stressors may allow scientists to develop ways of protecting crops from increasingly harsh climate conditions.

Tiny compartments in plant cells called chloroplasts house the molecular machinery of photosynthesis. This machinery is made up of proteins that must be assembled and maintained. Harsh conditions such as excessive light can push this machinery into overdrive and damage the proteins. When this happens, a protective response kicks in called the chloroplast unfolded protein response (cpUPR).

“Until now, it was not known how cells evaluate the balance of healthy and damaged proteins in the chloroplast and trigger this protective response,”

says co-senior author Silvia Ramundo, Postdoctoral Fellow in the Walter Lab at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

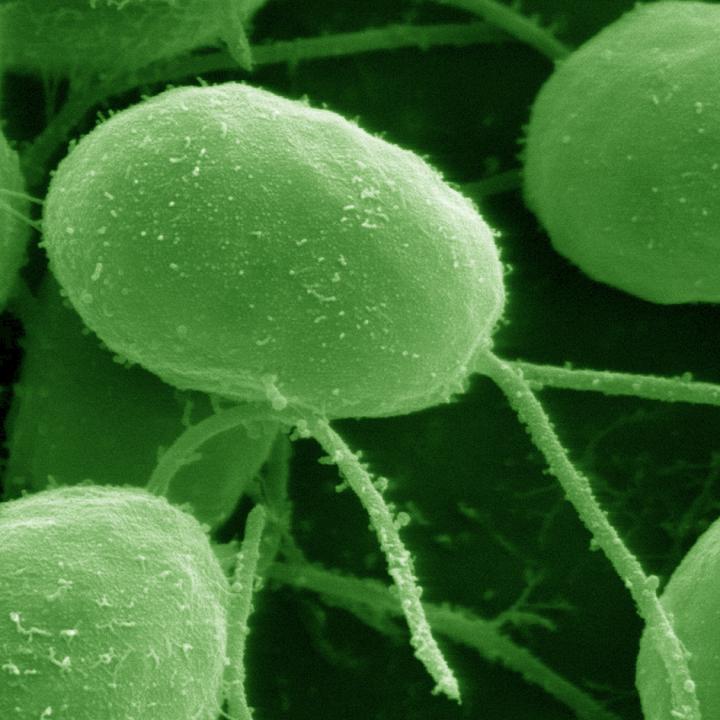

To learn more, the UCSF team genetically engineered an alga called Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to produce fluorescent cells in response to damaged chloroplast proteins. They then searched for mutants in the cells that would no longer fluoresce, meaning they were unable to activate the cpUPR.

“Open annotations. The current annotation count on this page is 0.These experiments led the team to identify a gene called Mutant Affected in Retrograde Signaling (MARS1) that is essential for turning on the cpUPR. “Importantly, we found that mutant cells in MARS1 are more sensitive to excessive light, are unable to turn on the cpUPR, and die as a result,” explains lead author Karina Perlaza, a graduate student in the Walter lab. Restoring MARS1, or artificially turning on the cpUPR, protected the algae’s cells from the harmful effects of excess light on chloroplast proteins.

“Our results underscore the important protective role of the cpUPR,” says co-senior author Peter Walter, Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at UCSF, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “The findings suggest that this response could be harnessed in agriculture to enhance crop endurance to harsh climates, or to increase the production of proteins in plants called antigens that are commonly used in vaccines.”

Read the paper: eLife

Article source: eLife

Image credit: Dartmouth College Electron Microscope Facility, Louisa Howard