Whether Guard Cells (GCs) carry out photosynthesis has been debated for decades. Earlier studies suggested that guard cell chloroplasts (GCCs) cannot fix CO2 but later studies argued otherwise. Until recently, it has remained controversial whether GCCs and/or GC photosynthesis play a direct role in stomatal movements. Dr Boon Leong LIM, Associate Professor of the School of Biological Sciences of the University of Hong Kong (HKU), in collaboration with Dr Diana SANTELIA from ETH Zürich, discovered GCs’ genuine source of fuel and untangled the mystery. The findings were recently published in prestigious journal Nature Communications. The paper was selected as a Featured Article by the journal’s editor.

In the morning, sunlight triggers stomata, which are tiny pores on plant leaves, to open. This let CO2 in and O2 out to boost photosynthesis. The opening of stomata consumes a large amount of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cellular energy currency, but the sources of ATP for stomata opening remained obscure. Some studies suggested that GCCs carry out photosynthesis and export ATP to the cytosol to energise stomata opening. In mesophyll chloroplasts, ATP and NADPH (nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate) are generated from photosystems, which are used as fuel for fixing CO2.

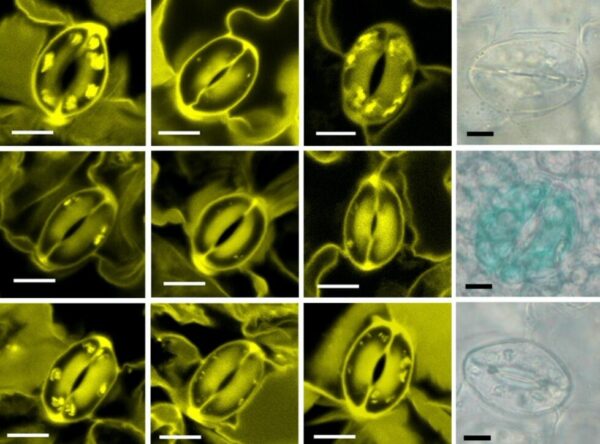

By employing in planta fluorescence protein sensors, the team of Dr Boon Leong LIM at HKU was able to visualise real-time production of ATP and NADPH in the mesophyll cell chloroplasts (MCCs) of a model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. “However, we could not detect any ATP or NADPH production in GCCs during illumination. Puzzled by this unexpected observation, we contacted an expert in guard cell metabolism, Dr Diana SANTELIA from ETH Zürich, for a collaboration,” Dr LIM said. Over the past decade, the SANTELIA lab provided deep and important insights into starch and sugar metabolism in the guard cells (GCs) surrounding the stomatal pores on the leaf surface.

In joint efforts, the team shows that unlike mesophyll cells (MCs), GC photosynthesis is poorly active. Sugars synthesised and supplied by MCs are imported into GCs and consumed by mitochondria to generate ATP for stomatal opening. Unlike MCCs, GCCs take up cytosolic ATP via the nucleotide transporters (NTTs) on chloroplast membrane to energise starch synthesis in daytime. At dawn, while MCs start to synthesise starch and export sucrose, GCs degrade starch into sugars to supply energy and increase turgor pressure for stomatal opening. Hence, the function of GCCs to serve as a store of starch is important for stomatal opening. While MCs fix CO2 in chloroplasts via the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle, CO2 fixation in the cytosol is the main pathway of CO2 assimilation in GCs, where the downstream product malate, is also an important solute to increase turgor pressure for stomatal opening. In conclusion, GCs behave more like a sink (receive sugars) than a source (provide sugars) tissue. Their function is tightly correlated with that of MCs to efficiently coordinate CO2 uptake via stomata and CO2 fixation in MCs.

“I was very excited when Dr Lim contacted me asking to collaborate on this project,” Dr Diana SANTELIA said. “We have been trying to clarify these fundamental questions using molecular genetics approaches. Combining our respective expertise has been a winning strategy,” she continued.

Dr Sheyli LIM, the first author of the article and a former PhD student of LIM’s group remarked: “The in planta fluorescence protein sensors we developed are powerful tools in visualising dynamic changes of the concentrations of energy molecules in individual plant cells and organelles, which allow us to solve some key questions in plant bioenergetics. I am happy to publish our discoveries in two manuscripts in Nature Communications using this novel technology”.

Read the paper: Nature Communications

Article source: The University of Hong Kong

Image credit: The University of Hong Kong