Use of saline water to irrigate crops would bolster food security for many arid countries; however, this has not been possible due to the detrimental effects of salt on plants. Now, researchers at KAUST, along with scientists in Egypt, have shown that saline irrigation of tomato is possible with the help of a beneficial desert root fungus. This represents a new key technology for countries lacking water resources.

“Salt in irrigation water is one of the most significant abiotic stresses in arid and semiarid farming,” says former KAUST postdoc Mohamed Abdelaziz, who worked on the project team alongside Heribert Hirt. “Improving plant salt tolerance and increasing the yield and quality of crops is vital, but we must achieve this in a sustainable, inexpensive way.”

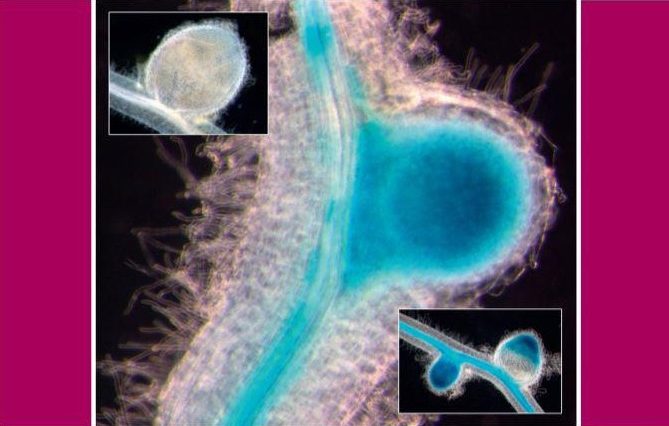

The root fungus Piriformospora indica forms beneficial symbiotic relationships with many plant species, and previous research indicates it boosts plant growth under salt stress conditions in barley and rice. While initial studies suggest the fungus can improve growth in tomato plants under long-term saline irrigation, the mechanisms behind the process are unclear. Also, little is known about the fungal-plant interaction throughout the entire growing season.

“Plant salt tolerance is a complex trait influenced by many factors,” says Abdelaziz. “The salt-tolerance mechanism depends on the correct activation of salt tolerance genes, stresses on cell membranes and the buildup of toxic sodium ions. We monitored growth performance over four months in tomato plants colonized with P. indica and in an untreated control group, both grown commercial style in greenhouses. We examined genetic and enzymatic responses to salt stress in both groups.”

The main threat to plants under salt stress is the buildup of sodium ions, which affects plant metabolism, and leaf and fruit growth. For example, excessive sodium in shoots and roots disrupts levels of potassium, which is vital for multiple growth processes from germination to enzyme activation.

The team showed that colonization by P. indica increased the expression of a gene in leaves called LeNHX1, one of a family of genes responsible for removing sodium from cells. Furthermore, potassium levels in leaves, shoots and roots of the P. indica group were higher than in controls. P. indica also increased levels of antioxidant enzyme activity, offering further protection.

“Colonization with P. indica boosted tomato fruit yield by 22 percent under normal conditions and 65 percent under saline conditions,” says Abdelaziz. “Colonizing vegetables provides a simple, low-cost method suitable for all producers, from smallholders to large-scale farming.”

Read the paper: Scientia Horticulturae

Article source: KAUST

Image credit: Capri23auto / Pixabay

Plants are under constant pressure from fungi and other microorganisms. The air is full of fungal spores, which attach themselves to plant leaves and germinate, especially in warm and humid weather. Some fungi remain on the surface of the leaves. Others, such as downy mildew, penetrate the plants and proliferate, extracting important nutrients. These fungi can cause great damage in agriculture.

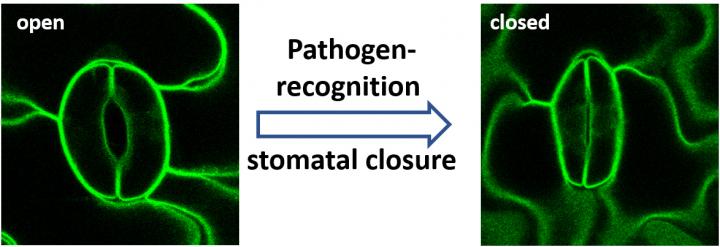

The entry ports for some of these dangerous fungi are small pores, the stomata, which are found in large numbers on the plant leaves. With the help of specialised guard cells, which flank each stomatal pore, plants can change the opening width of the pores and close them completely. In this way they regulate the exchange of water and carbon dioxide with the environment.

The guard cells also function in plant defense: they use special receptors to recognise attacking fungi. A recent discovery by researchers led by the plant scientist Professor Rainer Hedrich from Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, has shed valuable light on the mechanics of this process.

“Fungi that try to penetrate the plant via open stomata betray themselves through their chitin covering,” says Hedrich. Chitin is a carbohydrate. It plays a similar role in the cell walls of fungi as cellulose does in plants.

The journal eLife describes in detail how the plant recognizes fungi and the molecular signalling chain via which the chitin triggers the closure of the stomata. In addition to Hedrich, the Munich professor Silke Robatzek from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität was in charge of the publication. The molecular biologist Robatzek is specialized in plant pathogen defense systems, and the biophysicist Hedrich is an expert in the regulation of guard cells and stomata.

Put simply, chitin causes the following processes: if the chitin receptors are stimulated, they transmit a danger signal and thereby activate the ion channel SLAH3 in the guard cells. Subsequently, further channels open and allow ions to flow out of the guard cells. This causes the internal pressure of the cells to drop and the stomata close – blocking entry to the fungus and keeping it outside.

The research team has demonstrated this process in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress). The next step is to transfer the findings from this model to crop plants. “The aim is to give plant breeders the tools they need to breed fungal-resistant varieties. If this succeeds, the usage of fungicides in agriculture could be massively reduced,” said Rainer Hedrich.

Read the paper: eLife

Article source: University of Würzburg

Author: Robert Emmerich

Image credit: Michaela Kopischke

An international research collaboration has successfully assembled the complete genome sequence of the pathogen that causes the devastating disease Asian soybean rust.

The research development marks a critical step in addressing the threat of the genetically-complex and highly-adaptive fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi which has one of the largest genomes of all plant pathogens. Asian soybean rust has a devastating impact on soybean, an internationally important crop with 346 million tonnes produced globally.

In conditions favourable to its spread, the rust can destroy up to 90% of the soybean harvest. At present soybean growers in major areas of cultivation such as Latin America must use chemicals to protect crops.

The largest producer of the soybean is Brazil, where the combined cost of losses and disease control measures is US $2 billion per season.

The new dataset comprises the genome sequence of three isolates (K8108, MG2006 & PPUFV02) of which one has been assembled at chromosome level detail (PPUFV02). These three genomes will be hosted by the Joint Genome Institute and will be made available soon.

The three genomes will be repeat masked and annotated in the same way, to facilitate direct comparisons and inferences for the research community. This will enable researchers to study the molecular mechanisms of the pathogen, paving the way for breeding and engineering of disease-resistant crops.

The international consortium behind the project comprised 11 research and industry partners: The 2Blades Foundation, KeyGene, the Joint Genome Institute (JGI), Bayer, Syngenta, the Brazilian Company of Agricultural Research (Embrapa), l’Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA – France), the German Universities of Hohenheim and RWTH Aachen, The Sainsbury Laboratory, and the Federal University of Viçosa (Brazil).

The soybean rust pathogen is highly adaptive and disease resistance genes present in soybean have been overcome rapidly, and the pathogen is building resilience against the current generation of fungicides. These two factors leave few solutions for controlling the disease in the field.

Two of the three isolates that the consortium have sequenced are from Brazil, where the impact of soybean rust is a huge problem for farmers.

Phakopsora pachyrhizi has a highly complex genome, it is 60 times bigger than the yeast genome, composed of 93% repetitive elements and possesses two nuclei.

This complexity has delayed progress on the sequencing of this pathogen, and meant that high-end, next‐generation sequencing technologies were required to complete the task.

Given the importance of this disease, KeyGene made their PromethION machine (an industry first) and their sequencing and bioinformatics experts available pro bono. This way ultra-long DNA-sequencing reads of the pathogen and a high quality nanopore assembly were produced. This allowed Dr. Yogesh Kumar Gupta from the 2Blades group to generate a chromosome level assembly of the isolate PPUFV02, of which the DNA was provided by their long-term collaborator Prof. Sérgio Brommonschenkel at the Federal University of Viçosa (Brazil).

The consortium has also generated a transcriptome atlas of all the fungal structures and infection stages of the pathogen.

“Asian soybean rust is a critical challenge for soybean growers,” said Dr. Peter van Esse, leader of the 2Blades Group at The Sainsbury Laboratory, Norwich, one of the collaborators.

“A chromosome level genome assembly allows the scientific community to study, in unprecedented resolution, components of the pathogen that are critical for causing disease. This is a critical first step towards the design of transformative control strategies to combat this highly damaging pathogen.”

Peter van Esse

Access the sequence: Mycocosm

Article source: The Sainsbury Laboratory

Image credit: U. Steffens, Bayer Crop Science