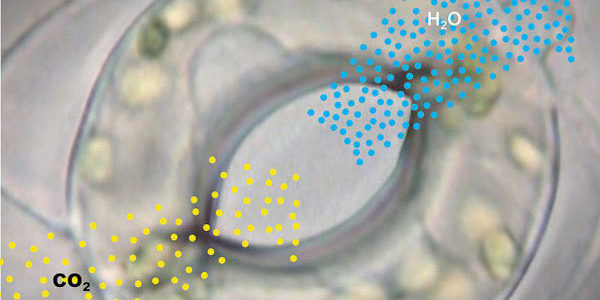

Plants face a dilemma in dry conditions: they have to seal themselves off to prevent losing too much water but this also limits their uptake of carbon dioxide. A sensory network assures that the plant strikes the right balance.

When water is scarce, plants can close their pores to prevent losing too much water. This allows them to survive even longer periods of drought, but with the majority of pores closed, carbon dioxide uptake is also limited, which impairs photosynthetic performance and thus plant growth and yield.

Plant accomplish a balancing act – navigating between drying out and starving in dry conditions – through an elaborate network of sensors. An international team of plant scientists led by Rainer Hedrich, a biophysicist from Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, has now pinpointed these sensors. The results have been published in the journal Nature Plants.

When light is abundant, plants open the pores in their leaves to take in carbon dioxide (CO2) which they subsequently convert to carbohydrates in a process called photosynthesis. At the same time, a hundred times more water escapes through the microvalves than carbon dioxide flows in.

This is not a problem when there is enough water available, but when soils are parched in the middle of summer, the plant needs to switch to eco-mode to save water. Then plants will only open their pores to perform photosynthesis for as long as necessary to barely survive. Opening and closing the pores is accomplished through specialised guard cells that surround each pore in pairs. The units comprised of pores and guard cells are called stomata.

The guard cells must be able to measure the photosynthesis and the water supply to respond appropriately to changing environmental conditions. For this purpose, they have a receptor to measure the CO2 concentration inside the leaf. When the CO2 value rises sharply, this is a sign that the photosynthesis is not running ideally. Then the pores are closed to prevent unnecessary evaporation. Once the CO2 concentration has fallen again, the pores reopen.

The water supply is measured through a hormone. When water is scarce, plants produce abscisic acid (ABA), a key stress hormone, and set their CO2 control cycle to water saving mode. This is accomplished through guard cells which are fitted with ABA receptors. When the hormone concentration in the leaf increases, the pores close.

The JMU research team wanted to shed light on the components of the guard cell control cycles. For this purpose, they exposed Arabidopsis species to elevated levels of CO2 or ABA. They did so over several hours to trigger reactions at the level of the genes. Afterwards, the stomata were isolated from the leaves to analyse the respective gene expression profiles of the guard cells using bioinformatics techniques. For this task, the team took Tobias Müller and Marcus Dietrich on board, two bioinformatics experts at the University of Würzburg.

The two experts found out that the gene expression patterns differed significantly at high CO2 or ABA concentrations. Moreover, they noticed that excessive CO2 also caused the expression of some ABA genes to change. These findings led the researchers to take a closer look at the ABA signalling pathway. They were particularly interested in the ABA receptors of the PYR/PYL family (pyrabactin receptor and pyrabactin-like). Arabidopsis has 14 of these receptors, six of them in the guard cells.

“Why does a guard cell need as many as six receptors for a single hormone? To answer this question, we teamed up with Professor Pedro Luis Rodriguez from the University of Madrid, who is an expert in ABA receptors,” says Hedrich. Rodriguez’s team generated Arabidopsis mutants in which they could study the ABA receptors individually.

“This enabled us to assign each of the six ABA receptors a task in the network and identify the individual receptors which are responsible for the ABA- and CO2-induced closing of the stomata,” Peter Ache, a colleague of Hedrich‘s, explains.

“We conclude from the findings that the guard cells offset the current photosynthetic carbon fixation performance with the status of the water balance using ABA as the currency,” Hedrich explains. “When the water supply is good, our results indicate that the ABA receptors evaluate the basic hormonal balance as quasi ‘stress-free’ and keep the stomata open for CO2 supply. When water is scarce, the drought stress receptors recognise the elevated ABA level and make the guard cells close the stomata to prevent the plant from drying out.”

Next, the JMU researchers aim to study the special characteristics of the ABA and CO2 relevant receptors as well as their signalling pathways and components.

Read the paper: Nature Plants

Article source: UNIVERSITY OF WÜRZBURG

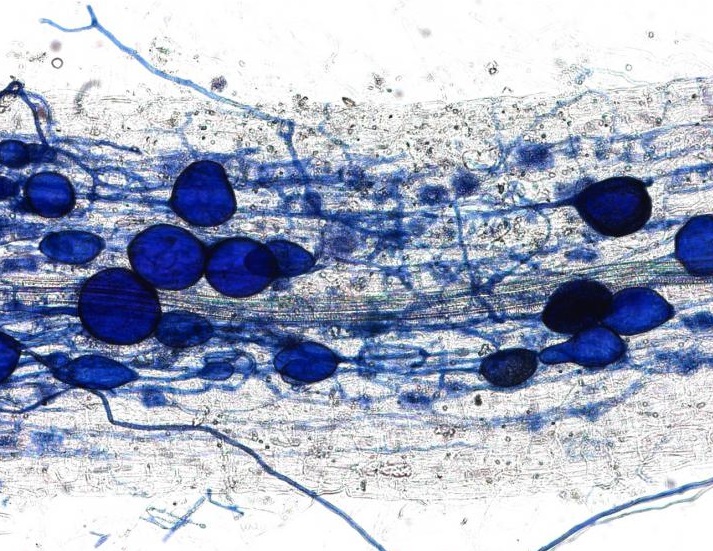

Image: Rainer Hedrich & Peter Ache / Universität Würzburg

Another fantastic year of discovery is over – read on for our 2016 plant science top picks!

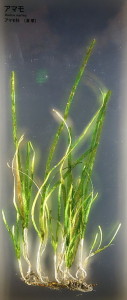

A Zostera marina meadow in the Archipelago Sea, southwest Finland. Image credit: Christoffer Boström (Olsen et al., 2016. Nature).

The year began with the publication of the fascinating eelgrass (Zostera marina) genome by an international team of researchers. This marine monocot descended from land-dwelling ancestors, but went through a dramatic adaptation to life in the ocean, in what the lead author Professor Jeanine Olsen described as, “arguably the most extreme adaptation a terrestrial… species can undergo”.

One of the most interesting revelations was that eelgrass cannot make stomatal pores because it has completely lost the genes responsible for regulating their development. It also ditched genes involved in perceiving UV light, which does not penetrate well through its deep water habitat.

Read the paper in Nature: The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea.

BLOG: You can find out more about the secrets of seagrass in our blog post.

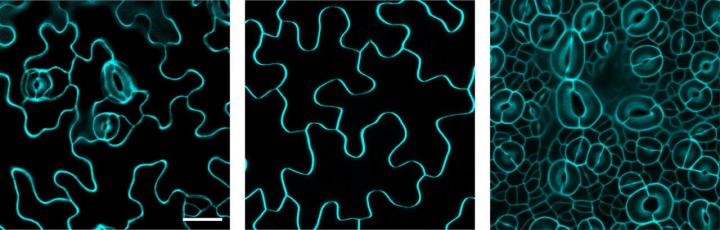

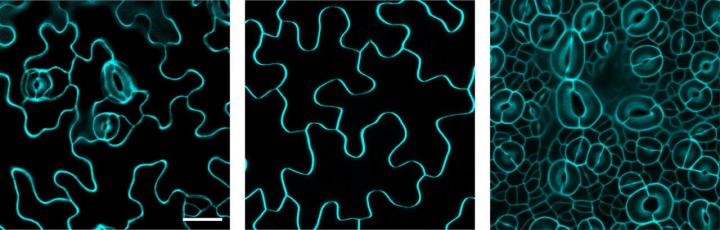

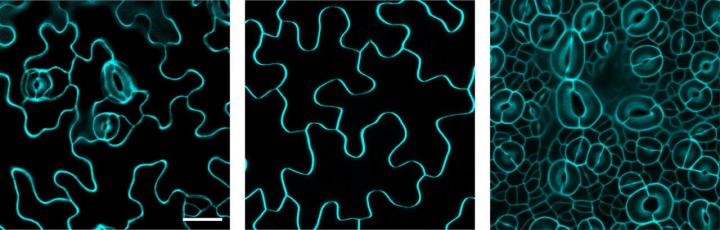

Plants are known to form new organs throughout their lifecycle, but it was not previously clear how they organized their cell development to form the right shapes. In February, researchers in Germany used an exciting new type of high-resolution fluorescence microscope to observe every individual cell in a developing lateral root, following the complex arrangement of their cell division over time.

Using this new four-dimensional cell lineage map of lateral root development in combination with computer modelling, the team revealed that, while the contribution of each cell is not pre-determined, the cells self-organize to regulate the overall development of the root in a predictable manner.

Watch the mesmerizing cell division in lateral root development in the video below, which accompanied the paper:

Read the paper in Current Biology: Rules and self-organizing properties of post-embryonic plant organ cell division patterns.

In March, a Spanish team of researchers revealed how the anti-wilting molecular machinery involved in preserving cell turgor assembles in response to drought. They found that a family of small proteins, the CARs, act in clusters to guide proteins to the cell membrane, in what author Dr. Pedro Luis Rodriguez described as “a kind of landing strip, acting as molecular antennas that call out to other proteins as and when necessary to orchestrate the required cellular response”.

Read the paper in PNAS: Calcium-dependent oligomerization of CAR proteins at cell membrane modulates ABA signaling.

*If you’d like to read more about stress resilience in plants, check out the meeting report from the Stress Resilience Forum run by the GPC in coalition with the Society for Experimental Biology.*

This plant root is infected with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Image credit: University of Zurich.

In April, we received an amazing insight into the ‘decision-making ability’ of plants when a Swiss team discovered that plants can punish mutualist fungi that try to cheat them. In a clever experiment, the researchers provided a plant with two mutualistic partners; a ‘generous’ fungus that provides the plant with a lot of phosphates in return for carbohydrates, and a ‘meaner’ fungus that attempts to reduce the amount of phosphate it ‘pays’. They revealed that the plants can starve the meaner fungus, providing fewer carbohydrates until it pays its phosphate bill.

Author Professor Andres Wiemsken explains: “The plant exploits the competitive situation of the two fungi in a targeted manner, triggering what is essentially a market-based process determined by cost and performance”.

Read the paper in Ecology Letters: Options of partners improve carbon for phosphorus trade in the arbuscular mycorrhizal mutualism.

The transition of ancient plants from water onto land was one of the most important events in our planet’s evolution, but required a massive change in plant biology. Suddenly plants risked drying out, so had to develop new ways to survive drought.

In May, an international team discovered a key gene in moss (Physcomitrella patens) that allows it to tolerate dehydration. This gene, ANR, was an ancient adaptation of an algal gene that allowed the early plants to respond to the drought-signaling hormone ABA. Its evolution is still a mystery, though, as author Dr. Sean Stevenson explains: “What’s interesting is that aquatic algae can’t respond to ABA: the next challenge is to discover how this hormone signaling process arose.”

Read the paper in The Plant Cell: Genetic analysis of Physcomitrella patens identifies ABSCISIC ACID NON-RESPONSIVE, a regulator of ABA responses unique to basal land plants and required for desiccation tolerance.

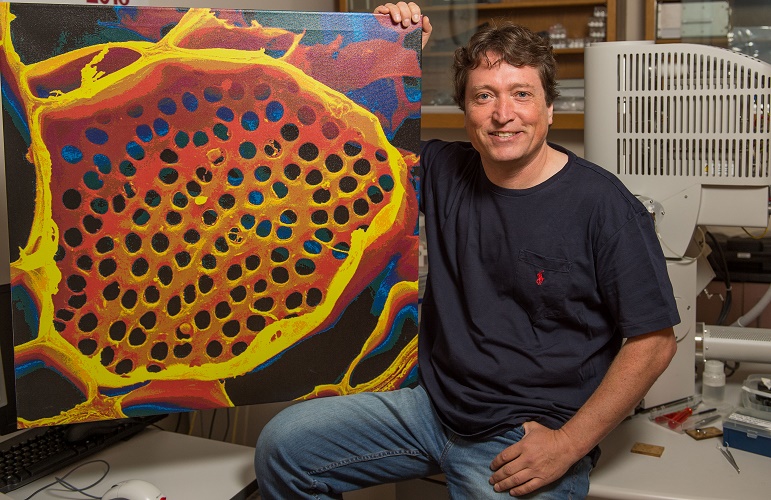

Professor Michael Knoblauch shows off a microscope image of phloem tubes. Image credit: Washington State University.

Sometimes revisiting old ideas can pay off, as a US team revealed in June. In 1930, Ernst Münch hypothesized that transport through the phloem sieve tubes in the plant vascular tissue is driven by pressure gradients, but no-one really knew how this would account for the massive pressure required to move nutrients through something as large as a tree.

Professor Michael Knoblauch and colleagues spent decades devising new methods to investigate pressures and flow within phloem without disrupting the system. He eventually developed a suite of techniques, including a picogauge with the help of his son, Jan, to measure tiny pressure differences in the plants. They found that plants can alter the shape of their phloem vessels to change the pressure within them, allowing them to transport sugars over varying distances, which provided strong support for Münch flow.

Read the paper in eLife: Testing the Münch hypothesis of long distance phloem transport in plants.

BLOG: We featured similar work (including an amazing video of the wound response in sieve tubes) by Knoblauch’s collaborator, Dr. Winfried Peters, on the blog – read it here!

Preserved remains of rope, seeds, reeds and pellets (left), and a desiccated barley grain (right) found at Yoram Cave in the Judean Desert. Credit: Uri Davidovich and Ehud Weiss.

In July, an international and highly multidisciplinary team published the genome of 6,000-year-old barley grains excavated from a cave in Israel, the oldest plant genome reconstructed to date. The grains were visually and genetically very similar to modern barley, showing that this crop was domesticated very early on in our agricultural history. With more analysis ongoing, author Dr. Verena Schünemann predicts that “DNA-analysis of archaeological remains of prehistoric plants will provide us with novel insights into the origin, domestication and spread of crop plants”.

Read the paper in Nature Genetics: Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley.

BLOG: We interviewed Dr. Nils Stein about this fascinating work on the blog – click here to read more!

Another exciting cereal paper was published in August, when an Australian team revealed that C4 photosynthesis occurs in wheat seeds. Like many important crops, wheat leaves perform C3 photosynthesis, which is a less efficient process, so many researchers are attempting to engineer the complex C4 photosynthesis pathway into C3 crops.

This discovery was completely unexpected, as throughout its evolution wheat has been a C3 plant. Author Professor Robert Henry suggested: “One theory is that as [atmospheric] carbon dioxide began to decline, [wheat’s] seeds evolved a C4 pathway to capture more sunlight to convert to energy.”

Read the paper in Scientific Reports: New evidence for grain specific C4 photosynthesis in wheat.

Professor Stefan Jansson cooks up “Tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables”. Image credit: Stefan Jansson.

September marked an historic event. Professor Stefan Jansson cooked up the world’s first CRISPR meal, tagliatelle with CRISPRy fried vegetables (genome-edited cabbage). Jansson has paved the way for CRISPR in Europe; while the EU is yet to make a decision about how CRISPR-edited plants will be regulated, Jansson successfully convinced the Swedish Board of Agriculture to rule that plants edited in a manner that could have been achieved by traditional breeding (i.e. the deletion or minor mutation of a gene, but not the insertion of a gene from another species) cannot be treated as a GMO.

Read more in the Umeå University press release: Umeå researcher served a world first (?) CRISPR meal.

BLOG: We interviewed Professor Stefan Jansson about his prominent role in the CRISPR/GM debate earlier in 2016 – check out his post here.

*You may also be interested in the upcoming meeting, ‘New Breeding Technologies in the Plant Sciences’, which will be held at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, on 7-8 July 2017. The workshop has been organized by Professor Jansson, along with the GPC’s Executive Director Ruth Bastow and Professor Barry Pogson (Australian National University/GPC Chair). For more info, click here.*

Phytochromes help plants detect day length by sensing differences in red and far-red light, but a UK-Germany research collaboration revealed that these receptors switch roles at night to become thermometers, helping plants to respond to seasonal changes in temperature.

Dr Philip Wigge explains: “Just as mercury rises in a thermometer, the rate at which phytochromes revert to their inactive state during the night is a direct measure of temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower phytochromes revert to inactivity, so the molecules spend more time in their active, growth-suppressing state. This is why plants are slower to grow in winter”.

Read the paper in Science: Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis.

A fossil ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) leaf with its modern counterpart. Image credit: Gigascience.

In November, a Chinese team published the genome of Ginkgo biloba¸ the oldest extant tree species. Its large (10.6 Gb) genome has previously impeded our understanding of this living fossil, but researchers will now be able to investigate its ~42,000 genes to understand its interesting characteristics, such as resistance to stress and dioecious reproduction, and how it remained almost unchanged in the 270 million years it has existed.

Author Professor Yunpeng Zhao said, “Such a genome fills a major phylogenetic gap of land plants, and provides key genetic resources to address evolutionary questions [such as the] phylogenetic relationships of gymnosperm lineages, [and the] evolution of genome and genes in land plants”.

Read the paper in GigaScience: Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba.

The year ended with another fascinating discovery from a Danish team, who used fluorescent tags and microscopy to confirm the existence of metabolons, clusters of metabolic enzymes that have never been detected in cells before. These metabolons can assemble rapidly in response to a stimulus, working as a metabolic production line to efficiently produce the required compounds. Scientists have been looking for metabolons for 40 years, and this discovery could be crucial for improving our ability to harness the production power of plants.

Read the paper in Science: Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum.

Another amazing year of science! We’re looking forward to seeing what 2017 will bring!

P.S. Check out 2015 Plant Science Round Up to see last year’s top picks!

Zostera marina. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s the ancient story of plant evolution: photosynthetic algae moved to damp places on land, eventually evolving more complex architecture, and spreading across almost all terrestrial habitats. To cope with the drier conditions, plants developed roots to absorb water, and vascular tissue to transport it; a waxy cuticle coating their surfaces to prevent evaporation; and microscopic pores called stomata that open to allow carbon dioxide to diffuse in for photosynthesis but close to prevent excessive water loss.

How, then, does eelgrass (Zostera marina) fit in to this tale? It’s a monocot descended from the flowering plants, but it has turned its back on dry land and returned to the sea; a rare feat that only appears to have happened on three occasions. The recent sequencing of the eelgrass genome has revealed several interesting insights into the dramatic genetic changes that have allowed it to adapt to what lead author Professor Jeanine Olsen described as, “arguably the most extreme adaptation a terrestrial (and even a freshwater) species can undergo.”

Sayonara to stomata

If you live in the sea, conserving water isn’t your main concern. Eelgrass was known to lack stomata, but genetic comparisons to other species, including its freshwater relative Spirodela polyrhiza, revealed the first surprise of the study: eelgrass has lost not only its stomata but also the genes involved in their development and patterning. “The genes have just gone, so there’s no way back to land for seagrass,” said Olsen.

A difference in defense

When angiosperms are attacked by herbivores or pathogens, their defense response typically involves the release of volatile secondary metabolites through their stomata. How can eelgrass release these compounds without stomata? The answer is: it doesn’t. The genome study found that eelgrass is missing crucial genes involved in making ethylene (an important hormone release in times of stress), as well as those responsible for producing non-metabolic terpenoids, which act to repel pests.

Selective pressures of the marine environment differ greatly from those of terrestrial habitats, so different pathways may be involved. Second, eelgrass has a wide repertoire of pathogen resistance genes, which suggests that it is exposed to a very different set of pathogens that may not respond to typical immune responses. Third, volatile secondary metabolites are often involved in attracting pollinators; this is not believed to be necessary in eelgrass, where submarine pollination occurs using the water itself.

Zostera marina – National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo. Public domain, CC0 1.0, via WikiMedia Commons.

Changing the cell wall

Eelgrass is subject to extremely salty conditions, and it’s had to adapt to osmotic stress. Unlike typical plant cell walls, eelgrass has engineered its cell wall matrix to retain water in the cell wall, even during low tide. This involves depositing sulfated polysaccharides and low methylated pectins in the cell wall matrix, but until its genome was sequenced no-one knew exactly how. It turns out that eelgrass has rearranged its metabolic pathways: “They have re-engineered themselves,” Olsen explains.

Living with a lack of light

Some species of Zostera can grow in water 50m deep, where light levels are reduced and shifted into a narrow wavelength range; ultraviolet (UV), red and far-red light have particularly low penetration after the first 1–2m of seawater. In a classic eelgrass ‘use it or lose it’ response, it has lost the UVR8 gene, which is responsible for sensing and responding to UV damage, as well as the phytochromes associated with red and far-red receptors. It does, however, retain the photosynthetic machinery, including photosystems I and II.

Unravelling angiosperm evolution

The recent eelgrass publication has revealed how this plant has either lost or adapted typical angiosperm traits to suit its needs, by ditching its stomata, volatile secondary metabolites and certain light sensing genes, or by altering the structure and function of the cell wall. It also developed adaptations that enable gas exchange, help pollen stick to submerged stigmas, and promote nutrient uptake.

Could these adaptations be useful in crop breeding? While a lack of defense compounds would probably be a step backwards, it would be extremely useful to understand how eelgrass copes with biotic stresses without them. Removing light receptors would also be problematic, but could eelgrass help us to develop crops that can grow in shaded conditions, perhaps in intercropping systems? What can we learn from eelgrass’ nutrient uptake and salt-tolerant adaptations?

Now that we have seen some of the secrets of eelgrass, how can we best make use of them?

Read the paper: The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea (Open Access)

Read the editorial: Genomics: From sea to sea (paywall)

Read the press release: Genome of the flowering plant that returned to the sea