James Wong trained as a botanist at Kew Gardens in London, UK, before embarking on a wide and varied career encompassing broadcasting, writing and garden design. He demonstrates his passion for plants in every strand of his work, and is making a significant contribution towards raising the profile of horticulture and the plant sciences within the UK. He took some time out of his busy schedule to speak to Amelia at the Global Plant Council.

James qualified with a Masters in Ethnobotany; the study of how people use plants, in 2006. This branch of the plant sciences is very relevant to tackling pressing issues such as food security and conservation.

James qualified with a Masters in Ethnobotany; the study of how people use plants, in 2006. This branch of the plant sciences is very relevant to tackling pressing issues such as food security and conservation.

Plants have provided humanity with essentially every aspect of our sustenance and material culture for millennia. Being a fusion of anthropology and botany, ethnobotany is vital to understanding everything we are and everything we do.

Humanity relies on an incredibly narrow range of plants to meet its needs, with just 3 crops providing up to 50% of our sustenance. This means civilization has pinned its future on just 0.00006% of the world’s edible plants!

With threats like climate change and a growing global population, it is simply not feasible to continue to marginalise 99.99994% of our crops. Learning about how to grow, prepare and eat those other plants is where the work of ethnobotanists is vital.

This is just one example of how ethnobotany is essential in helping combat some of the biggest threats our species are facing in the next century. Plant geeks will indeed save the world.

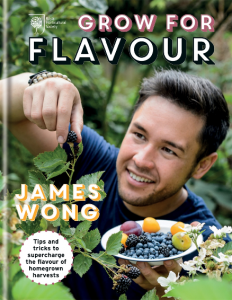

To meet the needs of a growing population, many resources are currently focused on  increasing productivity of our large scale farming systems. However, in his most recent book, Grow for Flavour, James explores how we can increase the nutritional quality of home-grown produce. Could small-scale food production such as personal allotments or gardens have any role to play in our future food production systems?

increasing productivity of our large scale farming systems. However, in his most recent book, Grow for Flavour, James explores how we can increase the nutritional quality of home-grown produce. Could small-scale food production such as personal allotments or gardens have any role to play in our future food production systems?

In short, no. My tiny urban garden is just 6x6m, and there is no way that it is ever going to make a significant contribution to my calorie intake.

However (and this is a big however), even in this tiny space I can get access to a range of fruit and vegetables that could make an important contribution towards certain micronutrients in my diet. Many of these, including key phytonutrients, are not found in the limited range of crops grown commercially, at least in large quantities.

Green Zebra tomatoes are a good source of tomatidine.

Photo credit: J Used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

For example tomatidine, a chemical found in green tomatoes, may help improve muscle tone and reduce atrophy according to some studies. It is not really found in any supermarket produce, yet I can easily grow 10 kgs of tasty, tomatidine-rich fruit like ‘Green Zebra’ each summer. Popped in the freezer they could provide me with an important source of this phytonutrient year round that would otherwise be almost totally absent in my diet.

Home gardens can make significant financial sense too, removing cost as a barrier to nutrient availability.

The garden design studio, Amphibian Designs, was co-founded by James in 2008. “I have always been fascinated by plants and I feel that designing with them helps me express that.” This fascination has led the studio to win four Royal Horticultural Society medals for its designs, including two gold medals at the Chelsea Flower Show. Gardening is perhaps something we might associate more with art and creativity than science. However, James finds that: “creating spaces with plants and arranging them to express an idea allows me to better understand their botany.” Furthermore, having a scientific rather than arts background can be advantageous in design.

I have no formal design training and find this actually allows me more creative freedom! I rarely know the design rules and conventions, so I don’t feel I need to slavishly devote my works to them. There is an awful lot of assumed knowledge and entrenched ideas in horticulture, much of which has no factual basis, and being an outsider means you get to circumvent all that.

Engaging the public with the plant sciences is becoming increasingly important yet the perception that plants are boring can be difficult to overcome. Could gardens and horticulture provide a way to approach this problem?

Absolutely. Humans instinctively find plants beautiful. Sadly, I do think UK horticulture has done a rather good job of suppressing this instinct in many people by holding up a singular, historical ideal as the dominant mode of what a ‘proper’ garden should be. Between the rustic woven willow and stately home symbolism, it can be very easy for many people (like me) to not associate themselves with gardening. Would food, fashion, music, art or film limit themselves to such as singular ideal? Of course not, and that explains their far more broad-based appeal.

One of the most popular stands I saw at Chelsea Flower Show this year was for the European Space Agency, and represented how plants would be grown in space to feed astronauts and fuel interplanetary discovery. The look of wonder in faces of the kids (of all ages) as they wandered through spoke volumes. What an amazing way to engage kids with science.

So, we can’t leave without asking one final question: any tips for the budding gardeners amongst our readers?

Plants always grow and look best when planted to echo how they would naturally grow in the wild. Doing so means you will have less work, healthier plants and a perfectly matching aesthetic almost every time. Google image your favourite plants in their wild habitat and try your best to match them. The rest will take care of itself!