A group of researchers from the University of Helsinki has found a groundbreaking new method to facilitate the observation of photosynthetic dynamics in vegetation. This finding brings us one step closer to remote sensing of terrestrial carbon sinks and vegetation health.

In 2017, the group from the Optics of Photosynthesis Lab (OPL) developed a new method to measure a small but important signal produced by all plants, and in this case trees. This signal is a called chlorophyll fluorescence and it is an emission of radiation at the visible and near-infrared wavelengths. Chlorophyll fluorescence relates to photosynthesis and the health status of plants, and it can be measured from a distance, for example from towers, drones, aircraft and satellites. Interpretation of the signal is, however, complicated and so far it has only been possible to measure it within discrete spectral bands from fully-grown trees in the field.

OPL devised a new technique that, for the first time, allowed them to observe from a distance the full spectrum (all colours) of fluorescence of mature trees growing in the forest. Measuring the whole spectrum of emission reveals information on both plant performance (how they photosynthesise) and the structure of the plants themselves.

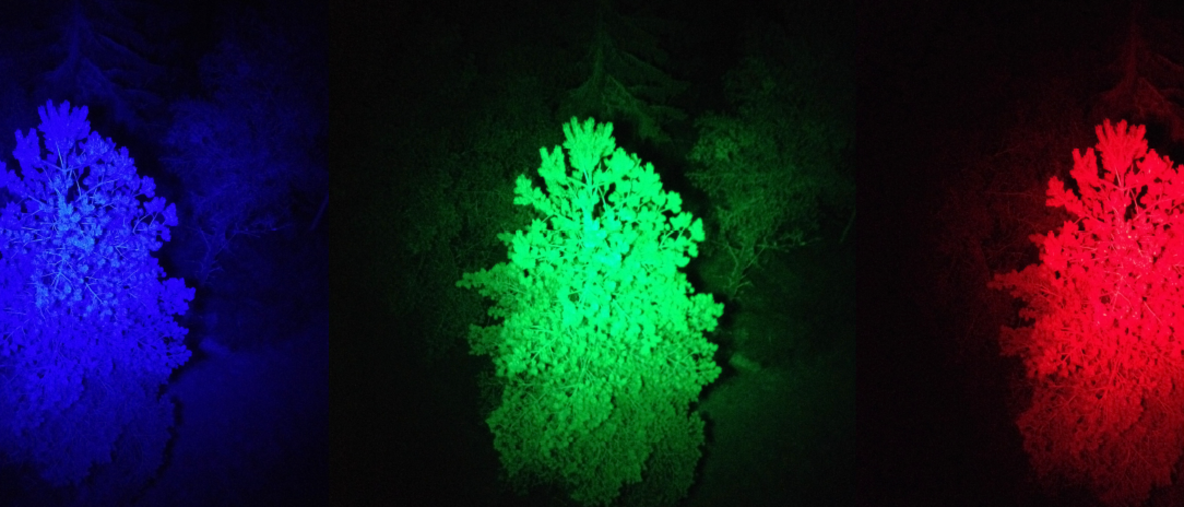

The issue with conventional remote sensing methods used so far has been that during daytime, most of the fluorescence distribution remains hidden from view, as the signal is so weak compared to sunlight. Therefore measuring fluorescence during daytime, commonly referred to as Solar-Induced Fluorescence (SIF), requires extremely sensitive and specialised instrumentation. The new technique differs from these previous efforts by using commercially available LED technology, which literately lights up the forest at night to reveal the full spectrum of emission of whole trees.

“We realised we could use the night as a ‘natural light filter’, so we went into the forest at night and attached a strong wavelength-restricted light source (a commercial disco-type light) to a tower that excited the fluorescence. Next, we used specialist scientific instrumentation, a spectroradiometer, also mounted in the tower to observe the signal”, describes Jon Atherton, researcher from the University of Helsinki Optics of Photosynthesis Lab at the Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR) / Forest Sciences of the University of Helsinki.

Combining night and light simplifies things: measuring fluorescence at night can be done with potentially cheaper (less sensitive) instruments and it provides data that is easier to interpret.

The link between fluorescence and terrestrial carbon sinks

The researchers’ new contribution puts us one step closer to “observing photosynthesis” by looking at the light emitted by plants, both on smaller scales (greenhouse, crops, forest stand) but also globally using satellites. The European Space Agency is preparing the FLEX satellite mission, which aims to map fluorescence globally. The hope is that fluorescence will be used to routinely estimate plant photosynthesis from space, which is the process that drives the terrestrial carbon cycle.

The role of forests in the uptake and assimilation of atmospheric carbon is crucial and widely discussed in the media. Measuring the exchange of carbon dioxide between forests and the atmosphere is accomplished with expensive instrumentation in specific places (flux tower sites) which produce localised estimates of fluxes (carbon exchange) close to the sites. This is where fluorescence enters into play by providing a remote sensing friendly means of estimating photosynthesis across the landscape by filling in the coverage (gaps) between the stations. Interpreting the data is challenging, but with the Light Emitting Diode Induced Fluorescence (LEDIF) technique there should be a significant leap forward.

“It is the potential for measuring fluorescence from space that really motivated us to do this work, although our results could have other applications too such as phenotyping, precision farming or forest nurseries. We hope that our data can be used to inform algorithms used to ‘retrieve’ fluorescence from space. Such algorithms work in a slightly different way to our spectral technique as they exploit dark atmospheric ‘lines’ to estimate fluorescence. Hence, the full emission spectrum remains effectively hidden in satellite data, and that is what our data reveals”, Jon Atherton adds.

Read the paper: Remote Sensing of Environment

Article source: University of Helsinki

Image: Albert Porcar-Castell