At July’s New Breeding Technologies workshop held in Gothenburg, Sweden, Dr. Staffan Eklöf, Swedish Board of Agriculture, gave us an insight into their analysis of European Union (EU) regulations, which led to their interpretation that some gene-edited plants are not regulated as genetically modified organisms. We speak to him here on the blog to share the story with you.

Could you begin with a brief explanation of your job, and the role of the Competent Authority for GM Plants / Swedish Board of Agriculture?

I am an administrative officer at the Swedish Board of Agriculture (SBA). The SBA is the Swedish Competent authority for most GM plants and ensures that EU regulations and national laws regarding these plants are followed. This includes issuing permits.

You reached a key decision on the regulation of some types of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants. Before we get to that, could you start by explaining what led your team to start working on this issue?

It started when we received questions from two universities about whether they needed to apply for permission to undertake field trials with some plant lines modified using CRISPR/Cas9. The underlying question was whether these plants are included in the gene technology directive or not. According to the Swedish service obligation for authorities, the SBA had to deliver an answer, and thus had to interpret the directive on this point.

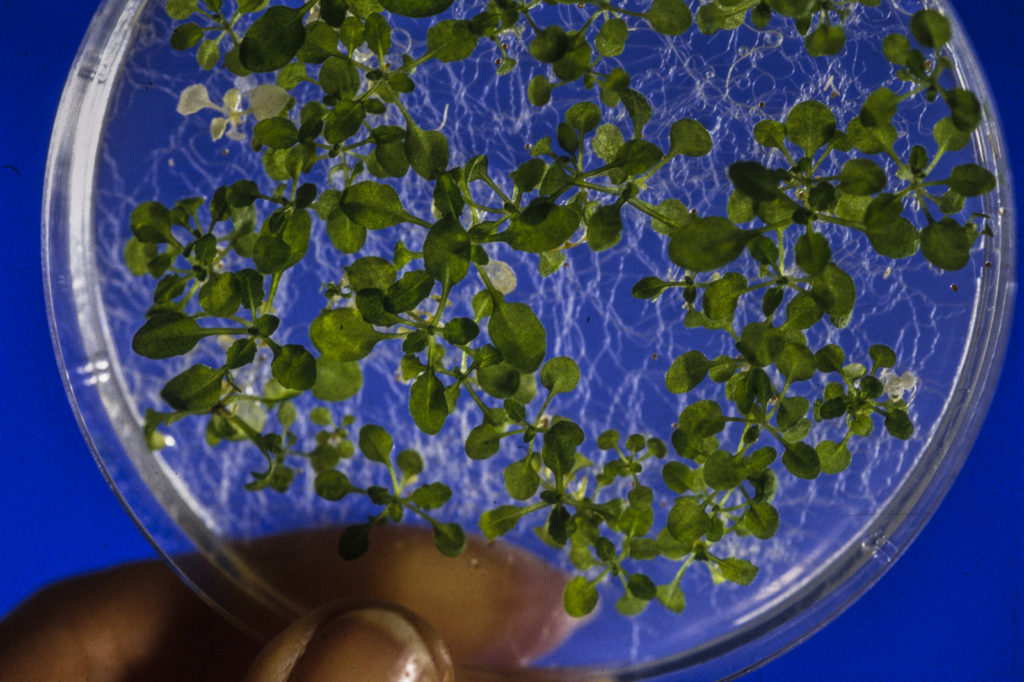

Image credit: INRA, Jean Weber. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Could you give a brief overview of Sweden’s analysis of the current EU regulations that led to your interpretation that some CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants are not covered by this legislation?

The following simplification describes our interpretation pretty well; if there is foreign DNA in the plants in question, they are regulated. If not, they are not regulated.

Our interpretation touches on issues such as what is a mutation and what is a hybrid nucleic acid. The first issue is currently under analysis in the European Court of Justice. Other ongoing initiatives in the EU may also change the interpretations we made in the future, as the directive is common for all member states in the EU.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a powerful tool that can result in plants with no trace of transgenic material, so it is impossible to tell whether a particular mutation is natural. How did this influence your interpretation?

We based our interpretation on the legal text. The fact that one cannot tell if a plant without foreign DNA is the progeny of a plant that carried foreign DNA or the result of natural mutation strengthened the position that foreign DNA in previous generations should not be an issue. It is the plant in question that should be the matter for analysis.

Image credit: Frost Museum. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

Does your interpretation apply to all plants generated using CRISPR-Cas9, or a subset of them?

It applies to a subset of these gene-edited plants. CRISPR/Cas9 is a tool that can be used in many different ways. Plants carrying foreign DNA are still regulated, according to our interpretation.

What does your interpretation mean for researchers working on CRISPR-Cas9, or farmers who would like to grow gene-edited crops in Sweden?

It is important to note that, with this interpretation, we don’t remove the responsibility of Swedish users to assess whether or not their specific plants are included in the EU directive. We can only tell them how we interpret the directive and what we request from the users in Sweden. Eventually I think there will be EU-wide guidelines on this matter. I should add that our interpretation is also limited to the types of CRISPR-modified plants described in the letters from the two universities.

Will gene-edited crops be grown in Europe in the future? Image credit: Richard Beatson. Used under license: CC BY 2.0.

We are currently waiting for the EU to declare whether CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited plants will be regulated in Europe. Have policymakers in other European countries been in contact with you regarding Sweden’s decision process?

Yes, there is a clear interest; for example, Finland handled a very similar case. Other European colleagues have also shown an interest.

What message would you like plant scientists to take away from this interview? If you could help them to better understand one aspect of policymaking, what would it be?

Our interpretation is just an interpretation and as such, it is limited and can change as a result of what happens; for example, what does not require permission today may do tomorrow. Bear this in mind when planning your research and if you are unsure, it is better to ask. Moreover, even if the SBA (or your country’s equivalent) can’t request any information about the cultivation of plants that are not regulated, it is good to keep us informed.

I think it is vital that legislation meets reality for any subject. It is therefore good that pioneers drive us to deal with difficult questions.

In June 2016, the UK Government will hold a public referendum for the people to decide whether or not Britain should exit the European Union. This contentious issue, popularly known as “Brexit”, has even divided the governing political party, with key parliamentary figures standing on either side of the debate.

There are many complex political issues for the UK to consider ahead of this referendum. One of these issues is: “what would be the consequences for UK agriculture if Britain were to leave the EU?” Professor Wyn Grant, a member of the Farmer–Scientist Network in the UK, tells us about a new report asking this very question.

by Wyn Grant

The Farmer–Scientist Network was set up by the Yorkshire Agricultural Society (UK) to facilitate practical cooperation between farmers and academics on the challenges facing agriculture. The Network felt there was a need to produce an assessment of the possible consequences of Brexit for agriculture. A working party was established, made up of leading experts on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and farmer members. I chaired this working party, and we produced what we hope is a comprehensive report, available here: http://yas.co.uk/charitable-activities/farmer-scientist-network/brexit.

In producing the Brexit report, one of our objectives was to provide information that farmers and others concerned with agriculture could use to question politicians during the referendum campaign. We also felt that agriculture and food had not been given sufficient attention during the negotiations and subsequent discussions. Should Brexit occur, our report draws attention to the issues that would have to be considered in exit negotiations.

In producing the Brexit report, one of our objectives was to provide information that farmers and others concerned with agriculture could use to question politicians during the referendum campaign. We also felt that agriculture and food had not been given sufficient attention during the negotiations and subsequent discussions. Should Brexit occur, our report draws attention to the issues that would have to be considered in exit negotiations.

When evaluating the implications of Brexit for agriculture, we expected there would be complexities and uncertainties, but these were, in fact, greater than we anticipated. One reason for this is that, although the Lisbon Treaty on which the EU is founded makes provision for Member States to leave the EU under ‘Article 50’, none have ever done so before. It is difficult to know in advance how Britain’s exit would proceed, but it would almost certainly be necessary to use the entire two-year negotiating window provided for in the Treaty. Another complication is that the UK Government has not undertaken any formal contingency planning for exit, so it is difficult to know what a future domestic agricultural policy would look like.

In the event of Brexit taking place, the Farmer–Scientist Network feels that an optimal arrangement for the UK would be to establish a free trade area with the rest of the EU, with tariff-free access for UK farm products to the internal market. However, we don’t think the EU would want to give too generous a deal for fear of encouraging other member states to think about the benefits of exit.

Currently, two ‘pillars’ of financial subsidy are awarded to stakeholders in EU agriculture. We believe that the existing ‘Pillar 1’ subsidies that are given to EU farmers would be vulnerable after Brexit. This is an important issue, as for many farmers these subsidies make the difference between making a profit and running at a loss. Supporters of Brexit argue that the savings made from contributions to the EU budget would more than allow for subsidies to continue to be paid at the existing level. However, this overlooks the fact that the UK Treasury has for a long time targeted these subsidies as “market distorting”, and in the current climate of austerity in the UK, they could be at risk of being phased out as a means to reduce public expenditure.

We did, however, think that the ‘Pillar 2’ subsidies directed at agri-environmental and rural development objectives would be continued in some form. This is in part because they are embedded in contracts that continue beyond 2020, and because they have a coalition of domestic support from outside the industry from environmental and conservation lobbies.

Some farmers resent what they see as excessive regulation emanating from Brussels. However, we think it is unlikely that many of these controls would be dropped or relaxed following Brexit. There are good reasons for regulations covering such areas as water pollution, pesticide use and animal welfare that have nothing to do with membership of the EU. Domestic support for such regulations would continue from environmental, conservation, public health, animal welfare and consumer organisations.

Some farmers hope that plant protection products that have been banned under EU regulations could be used after Brexit. However, there would still be domestic pressure to regulate these products and manufacturers might be unwilling to produce them just for the UK market.

The UK at present negotiates in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) as a part of an EU bloc which provides additional leverage against powerful countries such as the United States. The agreements that the EU has with ‘third’ countries (those outside of Europe) would have to be renegotiated on a single country basis. Supporters of Brexit are confident that this task could be completed within two years. However, given that the UK has relied on the negotiating resources of the European Commission, it does not have many international trade diplomats and the process could take considerably longer.

The horticulture industry in the UK is substantially dependent on migrant labour from elsewhere in the EU. This could not easily be replaced with domestic labour. It would be necessary to try and negotiate a new version of the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) – a scheme (redundant since 2013) that was established to allow migrant workers from certain countries outside of the EU to work in UK agriculture – to ensure that the sector would have the labour it needs to function.

Being part of a larger political community gives British farmers some political cover from countries where farming makes up a large share of GDP or has strong cultural roots. The Farmer–Scientist Network concluded that it was difficult to see Brexit as beneficial to UK agriculture. However, we also emphasised that there are broader considerations about UK membership that needed to be weighed in any voting decision.