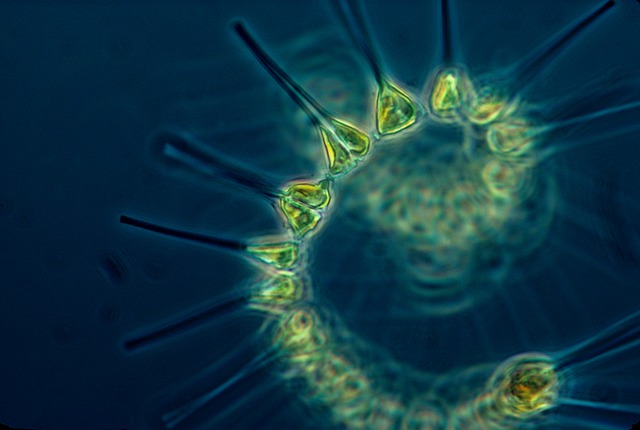

An international team of Earth system scientists and oceanographers has created the first high-resolution global map of surface ocean phosphate, a key mineral supporting the aquatic food chain. In doing so, the University of California, Irvine-led group learned that marine phytoplankton – which rely on the trace nutrient – are a lot more resilient to its scarcity than previously thought.

The researchers’ findings, published today in Science Advances, have important implications for climate change predictions. Ocean algae, or phytoplankton, absorbs a significant amount of carbon dioxide from the Earth’s atmosphere, thereby providing a valuable service in regulating the planet’s temperature.

“Understanding the global distribution of ocean nutrients is fundamental to identifying the link between changes in ocean physics and ocean biology,” said lead author Adam Martiny, UCI professor of Earth system science and ecology & evolutionary biology. “One of the outcomes of having this map is that we can show that plankton communities are extremely resilient even in nutrient-deficient environments. As lower ocean nutrient availability is one of the predicted outcomes of climate change, this may be good news for plankton – and for us.”

Dissolved inorganic phosphate plays an important biogeochemical role in the ocean habitat but is notoriously difficult to detect. Phosphorus is a crucial element of essential-to-life molecules such as adenosine triphosphate, which stores and transfers chemical energy between cells, and those found in DNA. Earth has a finite amount of phosphorus – unlike many other nutrients useful to phytoplankton – and it’s rare in the ocean.

Knowing how much is out there, and where, helps scientists understand the dynamics of the ocean food web and how it will be affected by alterations in ocean chemistry brought on by climate change. Martiny and his colleagues analyzed more than 50,500 seawater samples collected on 42 research voyages covering all of Earth’s ocean basins.

Martiny said that in addition to identifying regions where the mineral is in short supply, the team was able to discover previously unknown patterns of phosphate levels in major ocean basins in the Atlantic and Pacific.

“We have for too long had this simplistic view of a nutrient-rich ocean at high latitudes and ocean deserts at low latitudes,” he said. “However, in this paper we argue that our current predictions of nutrient stress may be too dire and that marine organisms are able to handle a limited supply of phosphate better than we previously thought.”

Read the paper: Science Advances

Article source: University of California – Irvine